Written by Kristen Lopez

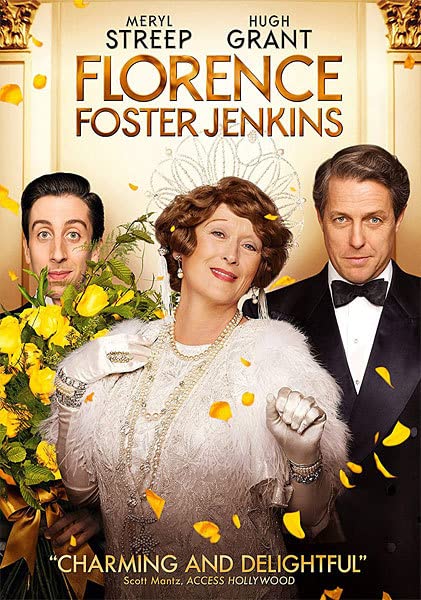

Best known to 30-somethings as the director of High Fidelity (or for one of my favorite crime dramas, The Grifters), Stephen Frears’ output over the last ten years has clung fast to the tea and crumpet set. Between the Academy Award-winning The Queen and the Academy Award-nominee Philomena, you can see Frears hopes third time’s a charm with Florence Foster Jenkins. The presence of Meryl Streep alone could make this a walk to the Oscars, but Frears suffers from diminishing returns in this take on the braveries of mediocrity reminiscent of this year’s Eddie the Eagle.

Florence Foster Jenkins (Streep) is a wealthy socialite dying from syphilis. Her dream is to be a coloratura soprano and sing in Carnegie Hall. The only problem: she stinks. But Florence refuses to let that stop her from doing what she loves.

As someone who once consumed everything Frears put out, I can’t say I’ve embraced his British series of films, mostly because they’re too delightfully trite and twee to have lasting impact. That’s not to say his work lacks panache; The Queen is remarkably well done, but that’s because it told a story worth telling. Florence Foster Jenkins isn’t necessarily a story worth telling, but one that ties in to looking at the banality of women’s lives, akin to last year’s Joy. If you couldn’t believe someone wanted to make a story about a woman and her mop, then you’ll similarly question the story of a woman who can’t sing a lick, but gets the chance to sing Carnegie Hall.

In the interest of full disclosure, I had never heard the name “Florence Foster Jenkins” till this week, but in doing research on her since, the movie doesn’t give the full scope of Foster Jenkins as a personality, one of the film’s many failings. Opening as the literal embodiment of the “angel of inspiration sent from on high,” Florence Foster Jenkins is depicted as a delightfully daffy woman always with a glittering dress handy, blissfully unaware of how bad a singer she is because her husband (Hugh Grant at his most charming) pays off critics and surrounds her with a bevy yes-men.

Like a Mary Pickford film, Florence is the poor little rich girl who everyone wants to keep away from the ills of the world, mainly critics. This is at odds with what’s known about Foster Jenkins, who actually sold tickets to her Carnegie Hall performance, and actively excluded critics and those who would be critical of her performance, this would have done so much towards giving us a woman active in her own life. Instead, Meryl Streep plays an aging princess confined to her tower, who shrieks at the slightest thing, whose husband endearingly calls her his “bunny rabbit,” and tucks her in at night. Streep plays the role fine, but it’s another showy character and doesn’t give Streep anything of substance. Streep plays Streep. The character is already sickly, so we know Streep will die beautifully at some point, and that’s one of several instances where audience will know what’s coming. Ultimately, there’s never any reason for us to root for Florence because she lives in a bubble.

There’s never any serious notion or discussion as to whether Florence herself is aware of her lack of skills. She records her music without desiring a second take; a throwaway line sees Florence talk about hiding her husband, St. Clair’s bad reviews to protect him and could have opened up a deeper look at the ways we lie to our loved ones. But does that mean she’s aware of what’s hidden from her? Because our heroine is in the dark so much, it makes Grant’s St. Clair look heartless, or at least apathetic to what he’s doing. He has a mistress, played by Rebecca Ferguson slaying in 1940s costumes, and an apartment, but apparently Florence’s knowledge is limited to the apartment as St. Clair makes the poor girlfriend hide in a closet. When the beleaguered mistress demands more of St. Clair’s time, it’s a bizarre mix of tones. St. Clair looks callous for lying to his wife and treating this other woman like a piece of meat – with talk of love being just that – but Ferguson’s Kathleen quite literally disappears into the night, as if the character is an impediment to be overcome.

Florence and her pianist, Cosme McMoon (Simon Helberg) are what makes Florence Foster Jenkins sing, so to speak. Helberg’s mild-mannered, quiet voice propels hilarity in situations that wouldn’t immediately call for laughter, and his befuddled expressions are on par with the likes of Don Knotts or Buster Keaton in terms of telling a story without words. McMoon has his own dreams and fear of failure, much like Florence and St. Clair, but where the other two’s “failure” isn’t wholly relatable, Cosme’s is. Because regardless of what Florence and St. Clair think, the stakes for them are completely personal – they won’t be going broke, that’s for sure – but Cosme dreams of being taken seriously, something that won’t happen with Florence. A special shout-out also is deserved for Nina Arianda who plays the crass Agnes Stark, a nouveau riche socialite with a mix of Jean Hagan’s voice and Madonna’s personality.

Writing a review that isn’t filled with florid praise for Florence Foster Jenkins is a moment of sheer irony, considering the script despises critics. The film gives two depictions of the theater critic: a shill who’ll write anything for money, while the other (played by Christian McKay) is a heartless jerk who doesn’t know anything about joy. Without spoiling anything, the final message Frears and crew lob critics’ way is enough just make you roll your eyes.

Florence Foster Jenkins continues the concept of “mediocrity rules.” Yes, I understand trying new things is courageous, but too often this is equated with all the seriousness of a true disability which is belittling to me personally. Outside of that, Florence Foster Jenkins is too polished and simple with a heroine too passive and subdued about her own life. Streep goes through the motions which, when you’re Meryl is fine, but won’t leave you demanding she get a nomination.