Film noir as a genre is rather over-subscribed. It existed for a relatively brief period in the ‘40s and ‘50s and was not a conscious genre at all. It was a retrospective, critically applied label to movies from largely the post-war period. Tough crime dramas where a character gets drawn into crime by greed or some other sin, and they find they can’t get out. They were largely cheap, largely sourced in short stories from crime magazines (the most prolific writer of them was Cornell Woolrich.)

But “film noir” sounds cool while a lot of other classic cinema, with its censorship proscribed values sound lame. So, there’s a mad scramble to apply the genre to any old movie that someone contemporary likes. This movie has some ambiguity to it? That’s a film noir!

So, some would call Fritz Lang’s fantastic and influential serial killer drama M a film noir, even if it’s nothing of the sort. It’s a police procedural, a suspenseful thriller, and a rather canny critique of the changes that were happening in German society in the early ’30s. But it’s not a film noir.

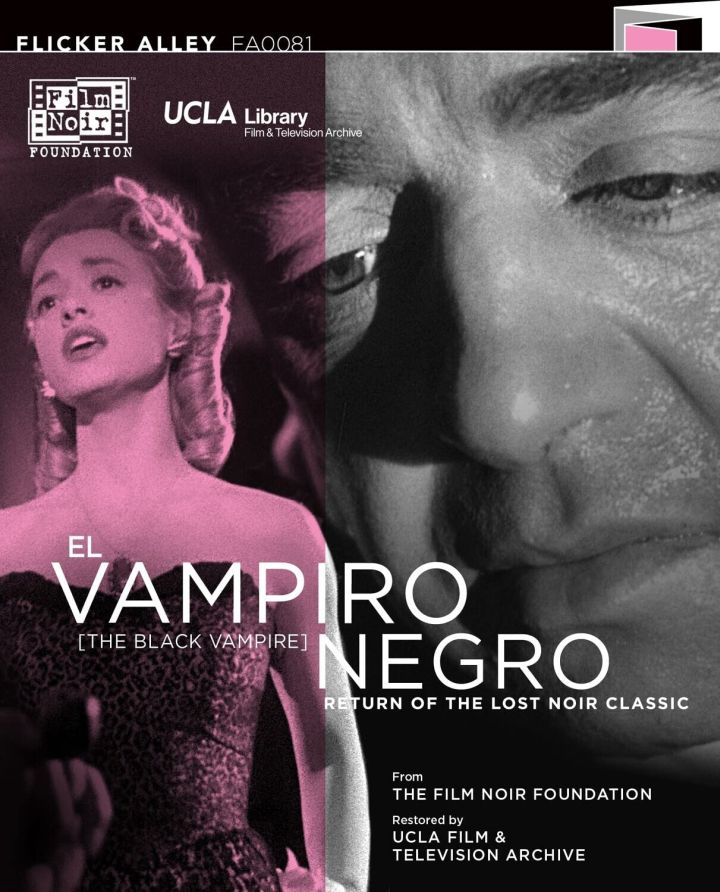

El Vampiro Negro is the title M was released as in Argentina. It’s also the name of this 1953 remake by director Roman Barreto. Flicker Alley, one of the current great American companies concerned with preserving international classic cinema, is calling this a “Lost Noir Classic.” I don’t know that I can agree with that. Though a crime film shot in stylish black and white with a dark outlook on life, I’d be hard pressed to categorize El Vampiro Negro (The Black Vampire) as film noir.

It is an able, if rather slim, adaptation of the original film. We open at the end, in a courtroom with the criminal already convicted, and the lawyers arguing whether he should be confined to an asylum or executed. His crime is the murder of several children. The criminal, Professor Ulber, is diminutive and rather pathetic, and the prosecutor is impassioned in his argument that the man is a monster and needs to be put to death.

We move backwards from there to the film’s story, which cycles between lead characters. Sometimes we follow the professor, sometimes the prosecutor, and most sympathetically, Amalia Keitel, a cabaret singer. She works in an unsavory place and tries to avoid publicity, for the sake of her young daughter. But one night she witnesses the murderer dumping a young girl’s body in the sewer just outside the cabaret.

The body is discovered by one of the underclass who lives in and around Buenos Aries’ rather impressive sewer system. The discoverer is poor and crippled, and so becomes an instant suspect for the crime. After a rough interrogation, the prosecutor demands he be locked up. He then immediately tells his underling he knows the man isn’t guilty. But someone has to be in jail.

The prosecutor starts as one of the most interesting characters in the film. He’s deeply committed to catching the serial killer, whom he dubs the Black Vampire. So committed, he’s ready to use extremely dubious means to catch the man. That includes locking up people he knows are not guilty and using children as bait in the hopes the vampire reveals himself.

But he’s also drawn to the singer, Amalia. His own wife is confined to a wheelchair. When he gets the singer alone, he uses tacit threats to reveal her unsavory life and get her child taken away, unless she yields to his advances. There’s a kind of powder keg inside the prosecutor character… but unfortunately, the movie, which is described in the promotional material as “proto-feminist,” simply uses him as part of its underlying theme of “man bad” instead of exploring him more fully.

It’s the downfall of El Vampiro Negro that it wants to explore the female characters more fully, so it rather unnecessarily flattens the males. The prosecutor becomes dull. The killer is revealed to essentially be hunting children because he’s unsuccessful with women, who humiliate him because he dares to be attracted to them.

There are several interesting sequences, and several nods to the original M. The killer whistles Grieg’s “In the Hall of the Mountain King”, which is a key in catching him. The underground, in this case the indigent rather than the criminal, are instrumental in finding the killer. The slow foot chase in M is more dramatic and interesting than the sewer-tunnel pursuit of the Black Vampire, which is largely cribbed from The Third Man.

El Vampire Negro, which was largely unknown until this restoration, is now released for first time ever on home video. It has been fully restored for this release. The high contrast black and white images are lovely, though the image occasionally exhibits an odd kind of warping. The center of the film occasionally seems to push outward, almost like it were being projected on a moving canvas. Without any other information, I can just assume that this is an artifact of the materials that survived of this nearly 70-year-old film.

I do not think I would call El Vampiro Negro a lost classic. But it is entertaining, occasionally thrilling, and visually arresting. Both in the black and white photography, and in the low-cut dresses worn by the Argentinian actresses that would not have passed ’50s American movie standards. Historically, it’s a fascinating exploration of a film story that has been done a few times before: Fritz Lang’s original, an American remake in 1951, and this mostly unseen version.

El Vampiro Negro has been released on Blu-ray and DVD by Flicker Alley. Extras on disc include a commentary by Argentina’s lead film archivist, Fernando Martin Pena. Video extras include “Introduction to El vampiro negro” (4 min) by Eddie Muller; “The 3 Faces of ‘M‘” (44 min), a documentary on three versions of M; and “Art in the Blood” (24 min), an interview with Daniel Vinoly, the director’s son.