One of the most effective themes of the recent Godzilla Minus One, which was the most successful Japanese language film in American box office history, is the horror of Japanese life in the immediate post-war era. The major metropolises of a largely industrialized nation had been destroyed. Partially by nuclear devastation, but largely through the fire-bombing that ravaged Tokyo. The nation was broken, and life for everyone was hard.

Buy Eighteen Years in Prison Blu-rayThere were several contemporary films about this hardship. One of my favorite Akira Kurosawa movies, Stray Dog, is about the difficulties of post-war life. It was a world of constant deprivation and social upheaval. Eighteen Years in Prison (1965) is largely about the extremes that people went to try and rebuild their lives.

In this film’s view, one of the viable forms of survival was organized crime. And our initial heroes, Kawada and Tsukada, are ready and able to engage in theft and violence to try and serve their devastated community. When a copper-wire heist goes wrong, Kawada is ready to be a distraction to let Tsukada get away, as long as he fulfills their promise: to create a real market for the locals, a sustainable economy, so daughters don’t have to sell their bodies to make it possible for their parents to live.

Kawada goes to jail, and while he fights inside against gangsters, corrupt cops, and the simple hell of incarceration, he’s content. Tsukada is taking his sacrifice to build a real community in their former war-torn neighborhood. And is also taking care of Isakao, a girl who Kawada had taken a personal interest in. He was her brother’s commander in the war and sent him on a Kamikaze mission.

In a dramatically satisfying but unlikely coincidence, Isakao’s long-lost brother ends up as Kawada’s volatile cellmate. He blames Kawada for his brother’s death. And it turns out Tsukada has taken the opportunity of Kawada’s sacrifice not to help their neighbors, but to enrich himself. He forms a Yakuza brotherhood and turns their ostensible market into a brothel. And eventually, through manipulation, he employs the brother to attempt to kill Kawada in prison.

The movie is a decent prisoner story, with corrupt guards, in house deals, and a compassionate warden trying to forge a new path. But thematically the film is largely about where Japan found itself in the aftermath of losing its war. They tried to be the Asian empire and failed. Occupied, their national identity shattered, the people could have gone towards mutual assistance, or every man for himself. Kamada sacrificed himself for the former. Tsukada took that sacrifice and chose the latter.

The film was directed by Tai Kato, who had served as an assistant director for Akira Kurosawa on Rashomon. Most of his post-war career was spent making period films, called “jidaigeki”, but Eighteen Years in Prison was a contemporary film. It’s about the tensions of the post-war life, and how the ideals that brought people together in the time where survival was not assured eroded into debauchery and greed when things became more stable.

Kato’s direction includes one of my favorite things about Japanese films, and that’s deeply stylized cinematography. Scenes are often framed so that only a small part of the screen contains any action. There are constant obstructions, framing devices, and lines bisecting the screen to carve it up and focus the audience’s attention on specific details. The movie has an odd marriage of social realism and near soap-opera melodrama. That’s Japanese cinema, though – the mix of near documentary observation and wild dramatic nonsense.

The back of the Blu-ray case notes mentions the film as a precursor to Fukasaku’s seminal Battles Without Honor and Humanity, and this film does channel some of that legendary film series energy. In particular, its radical de-romanticization of the Yakuza. Eighteen Years in Prison doesn’t go as far as that movie, with the insertion of a Yakuza boss who turns out to be the most noble of prison inmates. But it does highlight the grubbiness of powerful people’s actions, contrasted to their spoken high-minded ideals.

Of note is the focused, grim performance of lead Noboru Ando, who played Kawada. Ando was himself a former yakuza who’d spent six years in prison. He played in several films as various fictionalized versions of himself. The large knife scar on his left cheek is not movie makeup.

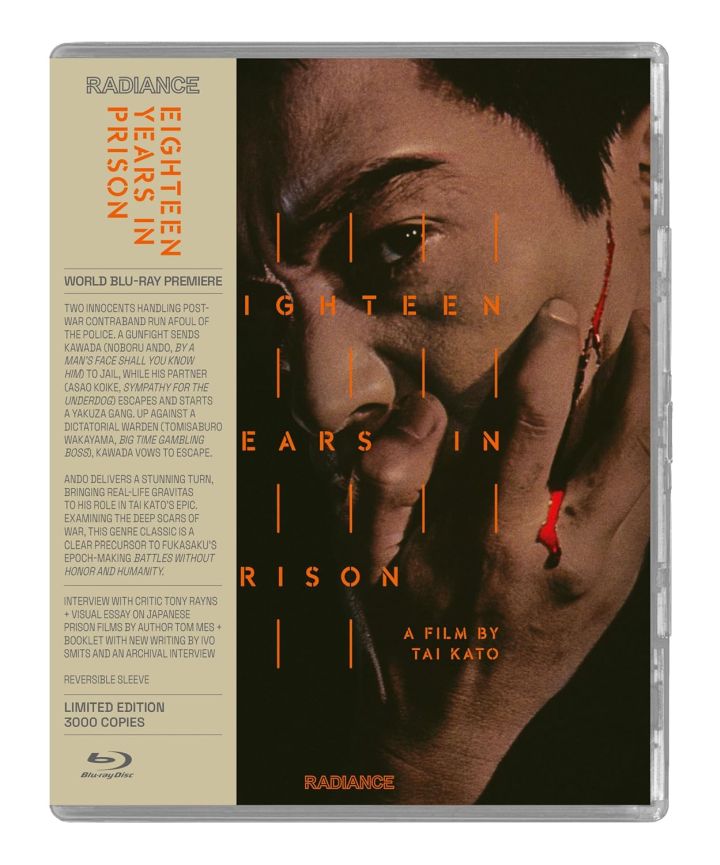

This Radiance Films release of Eighteen Years in Prison is the first time this film has been presented in high definition for home video. The print certainly shows its age, but it’s an above-average presentation of a nearly 60-year-old film. I like the film, though it doesn’t have the rawness or the energy of Fukasaku’s later series. Tai Kato’s film seems to posit there might have been a better way to navigate the world of Japan in the post-war. Fukasaku’s films assume that, essentially, life in that world of terror was basically impossible.

Eighteen Years in Prison has been released, for the first time, on Blu-ray by Radiance Films. Extras on disc include “Tall Escapes” (17 min), A Visual Essay by Tom Mes; a video essay by Tony Rayns (24 min); and a trailer. There’s also an essay by Tom Mes in the included booklet.