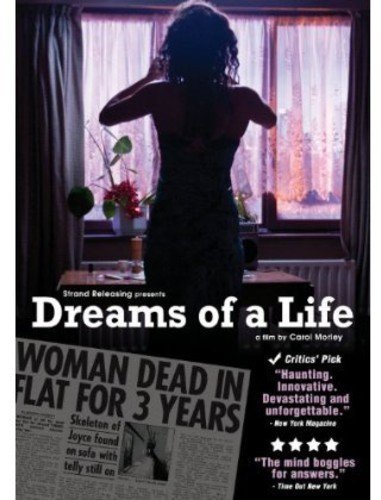

Written and directed by Carol Morley, Dreams of a Life is a stunning documentary that tells a story that could not possibly be true. It details the life and death of Joyce Vincent, who was discovered in her bedsit above a shopping mall in North London. She’d been dead for three years before her remains were found. Her television was still on and she was surrounded by unopened Christmas presents.

How could this have happened? How could anyone, let alone an attractive and generally well-liked 38-year-old, fade into the void in such a fashion without anyone catching on? Morley sets out to find answers, but the mystery isn’t easy to solve. When Vincent was discovered finally, there were no pictures and no reports from anyone who knew her.

In trying to piece together the puzzle, the filmmaker scattered advertisements in various London newspapers and publications. She also advertised on the Internet and on the side of a taxi. People who knew Joyce began to come out of the woodwork. Morley spent five years on the project, interviewing people from various stages of her life and slowly putting together the picture.

There is Martin, for instance, the first responder to Morley’s email campaign. He dated Joyce in the 80s and continued to see her for some time. In the picture, he says that she was probably the love of his life. Through eyes of regret and sadness, Martin puts Morley on the trail of some of the places where Joyce worked and some of the other acquaintances she kept.

Joyce apparently also had a musician landlord by the name of Kirk, who actually reveals the sound of her voice. Morley plays the recording to a few of her interview subjects. There is also Alistair, another potential love interest of Joyce’s who lived with her for a few years. And Mandy, who attended primary school with Joyce, held fast to her own beliefs about her old friend.

The interviews, presented simply against a backdrop of an A-Z London map blown up giant-size, reveal a compelling story and a sense of wonder as to how Joyce’s life came to such an end. People wonder if she was alone or lonely; they question the conception of association in society, how someone could’ve tumbled through the cracks in such a way.

Save for a couple of moments near the end of the film, Dreams of a Life stays away from hectoring about the state of our society. The focus is on Joyce and what her memories have in their wake. Here was a woman with dreams of being a singer, illustrated during one of the dramatizations by Zawe Ashton, and a woman who was sought after and admired by her peers.

Communication is doubtlessly a core theme, of course. Morley asks keen questions about the differences between being “contactable” and truly linked with others. Despite living in one of the most visible times in history, Dreams of a Life argues that we may be less in touch with one another than ever before.

There are quite a few unanswered questions. We don’t really know how Joyce died. There are some questions about an abusive boyfriend toward the end of her existence. She may have met Nelson Mandela or she may have been lying. What we know about Joyce we learn from other witnesses; their stories and memories may be stained by the passage of time or by their own considerations. This amounts to more questions.

There are probably many Joyce Vincents in our society. There are many who die alone and lonely, many who go through life seen constantly but never truly known. Dreams of a Life details this in engaging and captivating fashion, putting together the pieces of a mystery that is shaded with melancholy, isolation and desolation.