Written by Kristen Lopez

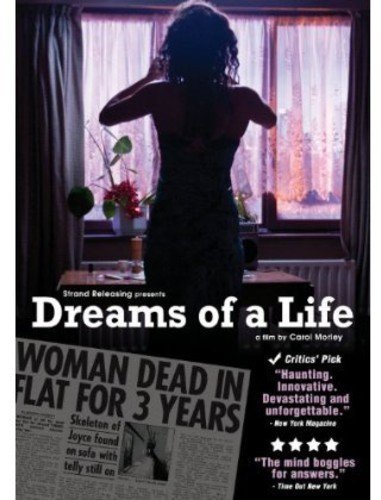

I applaud director Carol Morley for what she’s crafted with her documentary Dreams of a Life. The story of a forgotten body in a flat opens up the exploration of the beautiful, but oddly mysterious, life of a woman who should have had it all. Told through documentary interviews and filmed re-enactments, Dreams of a Life presents an incomplete look at a woman whose life leaves more questions than answers. The issue is Morley doesn’t seem to know where her story’s going. Interviews appear to repeat, the interviewers are never named so you have little idea of times and connections short of what you suss out for yourself, and items discovered in the disc’s bonus features should have been included in the film proper. Morley has a vision that could blossom into something great, and Dreams of a Life is a documentary you won’t forget, but it could have been stretched into greatness with a steadier hand.

In 2006, the body of a woman named Joyce Vincent was discovered in her London bedsit. Her skeletal body had been there, decomposing, for three years despite neighbors smelling the body and complaining about the noise from her television. Who was Joyce Vincent, and how did she end up dying alone and forgotten? Morley presents a documentary that doesn’t answer that question completely, but in interviewing Vincent’s friends and ex-lovers, paints a portrait of a woman who was a mystery to everyone she knew.

The story of Joyce Vincent is a fascinating source for a documentary. This was a woman who had four living sisters who didn’t declare her missing. In fact, if a repossession crew hadn’t showed up to evict her, she’d probably have been found a lot later. Unfortunately due to the length of time, no cause of death was ever proven and no proper inquest was opened into her death. Morley doesn’t use any narration to tell this story; instead questioning people who knew Vincent (who came forward after Morley put ads out asking for people who knew her), putting in newspaper clippings, and presenting speculative re-enactments of her life.

The interview subjects all cite the same things about Vincent. She was social, beautiful, and nice. I think what’s intriguing about the way her life is presented is how aloof she was. The word “nice” is such a common, bland way to describe someone, and yet all those interviewed who use it say “nice” with certain caveats. “She was nice, but not in a…way.” Later on, people start mixing up details they might have collected from Vincent, become unsure if she told them or if they imagined it. The film actually opens with the various interview subjects reacting to Vincent’s death. All cite they had no idea the Joyce Vincent they’d read about in the paper was the same woman they knew. The papers didn’t carry a photo for some reason, nor did the descriptions of this woman jive with what they knew about her. Several questioned all assumed she was in contact with family or had other friends when apparently that wasn’t the case. A few of the interview subjects describe Vincent as a chameleon; being a woman who didn’t have her own interests but molded herself to fit those around her. Several also mention the contradictions inherent in their descriptions of her, such as the fact she didn’t have any interests yet was filled with ambition. By the end Vincent herself is as much of a dream as the life others thought she led.

Morley presents a woman who was living during some interesting times. I don’t know much about British history throughout the ’80s and ’90s, but Vincent ran in impressive circles. She dreamed of being a singer for a small time and met singers like Stevie Wonder who she once had dinner with. The final image of the film is of Nelson Mandela giving a speech soon after being released from jail. Joyce Vincent is seen in the tape, leaving the audience with the hope that a piece of her won’t be forgotten. The film lightly touches on the racism of the ’80s but it’s light and doesn’t come across as strongly as it should. It’s obvious it should be developed in a different documentary.

The flaws in Dreams of a Life have to lie at Morley’s feet. For some reason she never gives names to the subjects. I didn’t know who they were, or who they were in relation to Vincent; they just start talking about their memories of her. In a way you’re stuck putting the pieces together as well trying to remember all these people and whenabouts they met her. The narrative device of re-enactments is good, especially the role of Vincent by the beautiful Zawe Ashton, but I would have liked some narration or text to orient times or locations.

The DVD itself has a lean amount of bonus content. The film’s trailer, as well as trailers for other films put out by company Strand Releasing are included. The only film-specific feature is a 27-minute behind-the-scenes featurette entitled Recurring Dreams. Really it just feels like a series of deleted scenes that are cobbled together. You have further discussions with the interview subjects, footage of Morley at a Q&A, footage of Ashton talking as Vincent. Two big pieces of info are included in this feature that should have been included at some point in the film, maybe via text at the end. One, is that all the content from Joyce Vincent’s flat was destroyed due to contamination so no one knows who the Christmas presents she was wrapping when she died were for. It also includes a written statement by her family briefly explaining why they wouldn’t participate and how they did try to find her. Those are two crucial questions the audience is left to ask that should be placed in the film proper, not buried in bonus features.

“It was like she never really existed. Like she was a figment of our imagination.” That is the best way to sum up Dreams of a Life. Despite its flaws in documentary technique, the film is haunting look at a life ignored, the ways people touch our lives, and how people are never who they appear. The documentary tells a riveting story worth seeking out.

Grade: C

Dreams of a Life will be available on DVD on Dec 11, 2012.