When I asked to review this film, Cinema Sentries publisher Gordon S. Miller, remembering that I had just reviewed the 1941 adaptation starring Spencer Tracy and Ingrid Bergman, dubbed me the site’s Jekyllologist (or is that Hydeologist?). What he didn’t know was that I had also just watched the silent film adaptation from 1921. I’m not sure I’d go so far as calling myself an expert on this particular story, especially since I’ve never actually read the book by Robert Louis Stevenson, but it has been interesting watching these cinematic adaptations and comparing how they’ve adopted Stevenson’s tale.

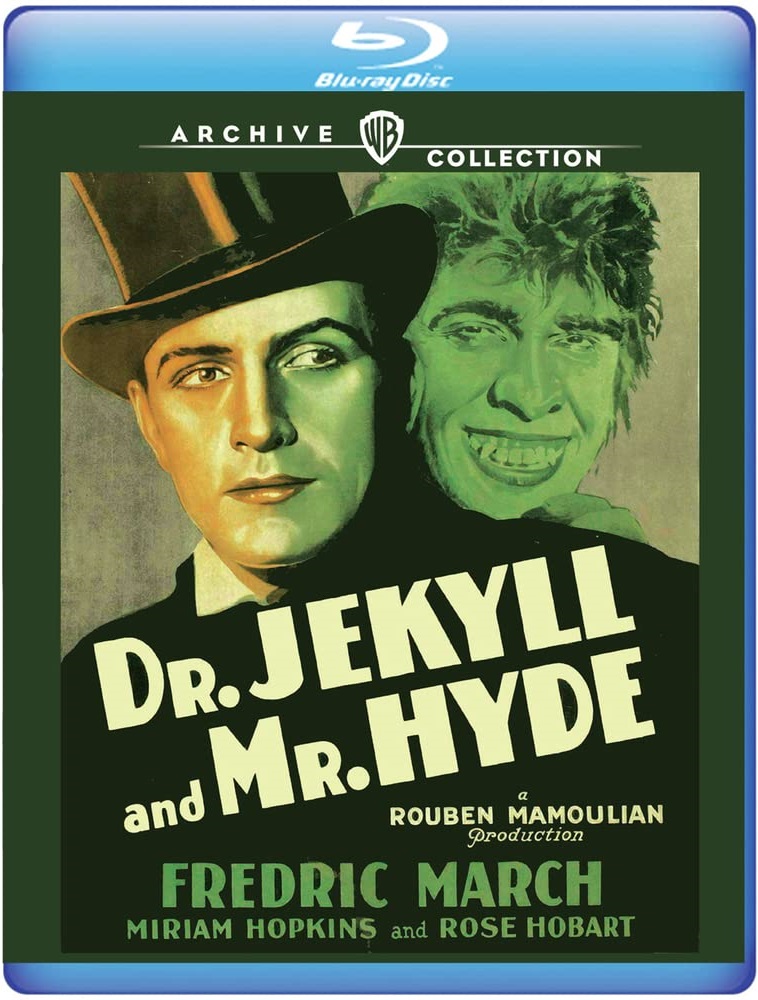

The 1941 film is essentially a remake of this version from 1931 in that it alters the story in the same way, adding in a love story and excising the bits it didn’t deem necessary to include. If you want to get technical, this version follows the basic plot of the 1887 play written by Thomas Russell Sullivan. Since I covered the story in my earlier review, I’ll not be rehashing all the details of the plot except to summarize like this: Dr. Jekyll (Fredric March) believes that every man contains two sides of himself – evil and good – like two sides of a coin. His experimentation has led him to believe that he can create a formula that will allow each side to exist without the other. Not having anyone else to experiment on he takes the formula himself and becomes a malevolent force he calls Mr. Hyde. Mayhem ensues.

It is interesting to me that Dr. Jekyll, in every version of the story I’ve seen thus far, never seems to ponder what one might do with the evil side of himself once successful in separating the two. It is never intended to be a physical transformation, separating the two selves into separate bodies, so maybe he just thinks he can do like the rest of us do and push down our darker impulses deep inside himself. Or maybe everybody knows it would be a boring story without Mr. Hyde following his id.

Interestingly, this version which was made a full 10 years before the Tracy adaptation is actually more risque than the latter. You can give thanks to the Production Code for that. The barmaid, Ivy Pearson (Miriam Hopkins). is much more suggestive in her seduction scene, stripping down to nothing before she slips under the covers and gives Jekyll the come hither. The film doesn’t quite show her completely naked body but it shows more than enough skin to know what’s going on. In general, the film is much more explicit (or as explicit as a film from 1931 was ever going to be) in revealing Hyde’s depravity than the 1941 version was allowed to do. When the film was re-released in 1936, the Production Code demanded more than eight minutes worth of edits.

What really makes this version special are the special effects. How they transformed Jekyll into Hyde seemingly in real-time on screen was a closely guarded secret for decades. Director Rouben Mamoulian finally revealed it in The Celluloid Muse, a book not released until 1969. Makeup was applied in contrasting colors and then color filters were used to either reveal or conceal the makeup. Since the film was in black and white, the colors do not show on screen. For the application of prosthetics, subtle cuts were made in the editing. The camera moves up and down March’s body from his head to his toes. This was shot several times with the actor in his color-shaded makeup, and then with different bits of the prosthetics and wigs on. Cuts were made when the camera was on his torso with the different shots edited in. Unless you are very carefully paying attention, the cuts seem invisible.

March is quite wonderful in the dual role. Spencer Tracy gets an extra point for his version of the character because I’m so used to watching him play good guys that his transformation is more exciting, but I’d give March the upper hand in terms of actual performance. Overall, I’d give this film the higher rating not only because it was the earlier version and thus more original, but that it really is the better film. But they do make a really interesting double feature.

This new disk from the Warner Archive includes a new commentary by Dr. Steve Haberman and Constanine Nasr, an archival commentary by Greg Mank, and Fredric March’s 1950 radio performance re-creating his role as “Jekyll & Hyde”.