In his latest feature film, veteran animation auteur Michel Ocelot immediately toys with audience perceptions by opening on what appears to be a tribal African village before zooming out to reveal the scene taking place in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower, a virtuoso sequence that draws viewers into guessing about the film’s direction. After three previous feature films set in Africa starring the character Kirikou, not to mention the timing of this film’s U.S. release coinciding with the usual seven-year gap between each of the Kirikou films, it’s easy to imagine that we’ll explore more of the tribal village in Paris here. Instead, Ocelot has other ideas for his latest flight of fancy, including the interesting tidbit that the village actually represents the Pacific island territory of New Caledonia, not Africa.

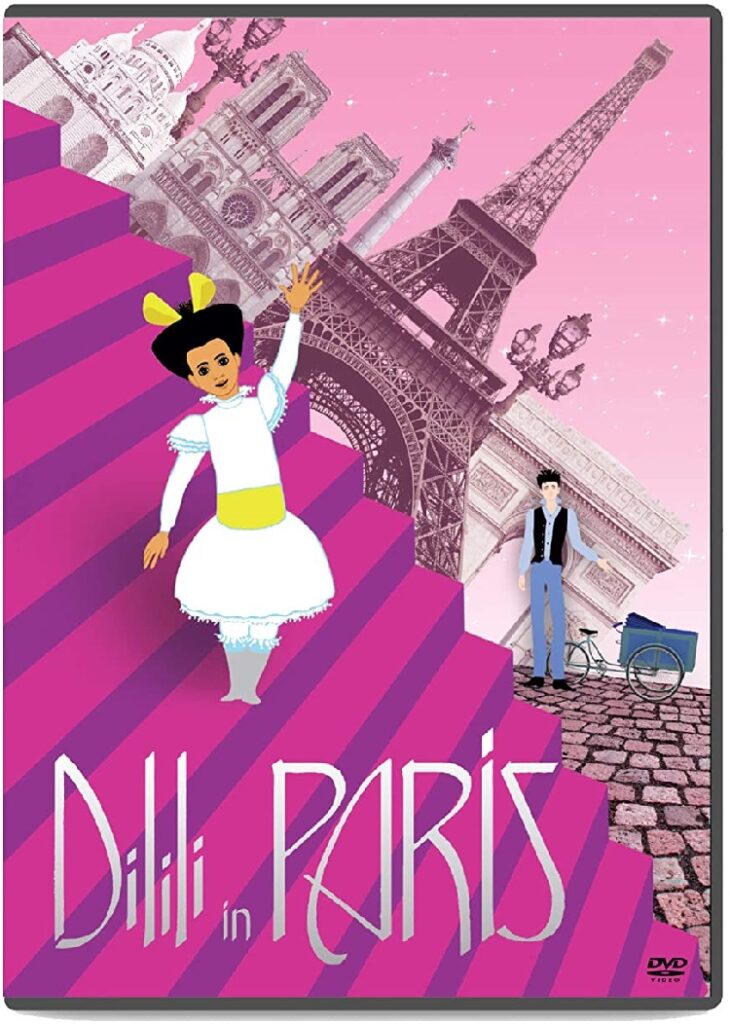

Dilili in Paris follows a young mixed-race girl from the faux tribal village as she explores Paris at the turn of the 20th century, the Belle Epoque era. She was brought to Paris from New Caledonia to star in the indigenous village recreation at the Eiffel Tower, a seemingly odd idea with basis in historical fact. As a native French speaker, she’s able to freely roam the city, even more so after she makes the acquaintance of Orel, a 20-ish bicycle messenger who happily shuttles her around. While at first they’re happy to travel around notable Parisian monuments and bump into famous people of the era (over 100 by Ocelot’s count), eventually they become aware of a sinister group of men called the Male Masters who are responsible for kidnapping and enslaving dozens of young girls. When Dilili falls into their trap but eventually escapes, she devotes herself to rescuing the other girls and destroying the evil patriarchal organization with the assistance of Orel and other new friends.

Ocelot has assembled a fascinating juxtaposition of ideas in the film, in one aspect a soaring love letter to the architectural wonders and luminaries of his home city but also a searing diatribe against racism, misogyny, and particularly the subjugation of women bubbling beneath the city’s surface. Although it’s set over a century ago, he clearly paints a parallel to modern times as a warning against repeating prior societal mistakes. While the film carries some decidedly dark undercurrents, he manages to keep it weighted toward the light, ultimately making it appropriate for all audiences without losing the power of his message.

Ocelot is such a singular talent that his name alone makes each animated film a must-see event, much like Hayao Miyazaki in Japan. He continues to innovate here, even as he approaches the end of his career, taking the unique approach of incorporating real Parisian photographic backgrounds as the sets for the film. He personally photographed the pictures over a span of four years, successfully directing a team of CG artists to remove all traces of modernity from his stills and also creating some virtual CG sets and objects with overlays of his photographs. The film is populated with 3D CG characters but painted in a flat, 2D manner that makes them appear closer to hand-drawn cel animation, a technique Ocelot has employed before but perfected here because, in his words, realistic 3D “doesn’t make me dream”. His new work is definitely the stuff of dreams, and a shining addition to his incredible animation legacy.