When I was a guest on the Turner Classic Movies podcast last fall, I engaged in a bit of premeditated hyperbole: The Motion Picture Production Code “ruined movies for thirty years,” I spat, tossing a reproduction of Hollywood’s infamous self-censorship guidelines (first enforced in 1934) on to the table in abject disgust.

As any TCM viewer knows, films of the so-called pre-Code era have become popular in recent years with modern audiences heretofore brainwashed to think of “old movies” as quaint and sex-less. And while it is true that the Code negatively impacted American filmmaking for more than a generation, it also can be said that I was exaggerating for impact.

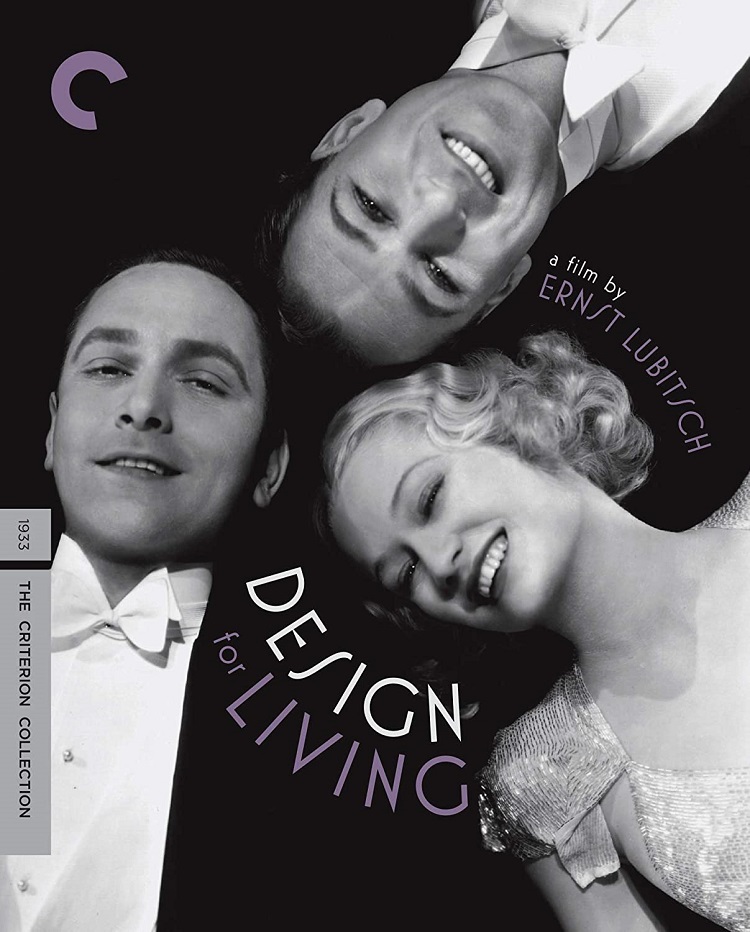

Obviously, the Code did not “ruin” every movie released between 1934 and the late 1950s, when directors like Otto Preminger began to routinely flout it. But it did alter the tone and content of American film for more than a generation, and you need only watch the delightful Criterion two-disc DVD of Ernst Lubitsch’s Design for Living to see my point.

Based loosely upon a Noel Coward play of the same name (first staged on Broadway in 1933 starring Coward, Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne), Lubitsch’s Design for Living is the story of three attractive Americans pursuing their respective art forms in Europe and practicing a somewhat Modernist approach to the art of love.

Gilda (Lubitsch favorite Miriam Hopkins) meets artist George (cast-against type Gary Cooper) and playwright Tom (Frederic March, smiling for a change) on the train to Paris. The attraction is immediate and Gilda “tries on” each of the men like hats (her analogy).

Unfortunately (or fortunately, depending upon your perspective), both of the strapping young gents are a perfect fit. Unable to choose, Gilda decides that the three will room together in a tiny Parisian flat – with one important condition.

“No sex,” she announces with charming optimism. “It’s a gentleman’s agreement.”

George and Tom channel their suppressed carnality into their work, under the creative and managerial guidance of Gilda, and the results are spectacular. Tom sells a play to a theatrical producer (the always dependable Franklin Pangborn), and heads off to London. But with one leg of their triangle missing, George and Gilda’s resolve collapses on top of each other.

“It’s true we have a gentlemen’s agreement,” Gilda says, draping herself over the dusty bed. “But unfortunately, I am no gentleman.”

If the movie ended right there, it would still be one of the most sexually frank films of the early sound era. But it doesn’t. Tom returns from success on the West End, while George happens to be off in Nice, painting a lucrative commission. Of course, Gilda and Tom rekindle their aborted romance and George finds himself the odd man out.

Not wanting to hurt either of her lovers, Gilda decides to marry her asexual boss Max Plunkett (Edward Everett Horton, typically hilarious) and heads for a new life as a society wife in New York. But George and Tom refuse to give up, much to the consternation of Max, or “Plunkett Incorporated,” as Tom calls him in a subtle moment of Depression era 99% Percent-ism.

I won’t give away the ending, but it’s kind of shocking. If you know people who don’t like classic film because everybody makes out like they’re kissing their grandma, show them Design for Living. And be prepared for some widened eyes.

Criterion’s DVD set is delightful, with a beautifully restored transfer of the film, a commentary on selected scenes by William Paul, author of Ernst Lubitsch’s American Comedy, and an interview with film historian and screenwriter Joseph McBride.

Also included in the set is a 1964 British television production of Coward’s play, adapted for ITV’s Play of the Week series. The play is rather blandly staged, but it’s fascinating to see how little of Coward’s words and intent Lubitsch and screenwriter Ben Hecht (His Girl Friday) retained for the film.The production is introduced on-camera by a 64-year-old Coward, and that five minutes alone is worth the purchase price.

Also included in the set (for reasons that completely escape me) is The Clerk, Lubitsch’s contribution to the film If I Had a Million, produced between Trouble in Paradise (1932) and Design for Living. For the record, I think Trouble is a better film, but Design wins a head-to-head because it turns the stereotype of “old movies” upside down.

The whole package is lovely to look at, with a spiffy book of liner notes that my graphic-designer girlfriend thought “looks expensive.” Even the box is gorgeous, with Cooper, Hopkins and March lying head to head, smirking like cats about to eat a canary.

And if you like Design For Living, look for the “Lubitsch Musicals” DVD box from Criterion’s Eclipse line, featuring The Love Parade (1929), Monte Carlo (1930), The Smiling Lieutenant (1931) and One Hour with You (1932). And dream about what could have been, had the pre-Code era lasted forever.