After befriending Salvador Dali and finding success in the surrealist movement with films like Un Chien Andalou and L’Age d’Or, Luis Buñuel was set on the path of greatness. But the Spanish Civil War threw that off and when Franco’s fascists won, he fled to the U.S. where he worked briefly for the Museum of Modern Art in New York and as a translator for Hollywood studios. Unsatisfied, he relocated to Mexico where he was once again able to make movies. He made an astonishing 21 movies during his 18 years as a Mexican filmmaker. Most of these films were barely seen outside of Mexico and therefore were largely unnoticed by the film world, but they are now beginning to be appreciated.

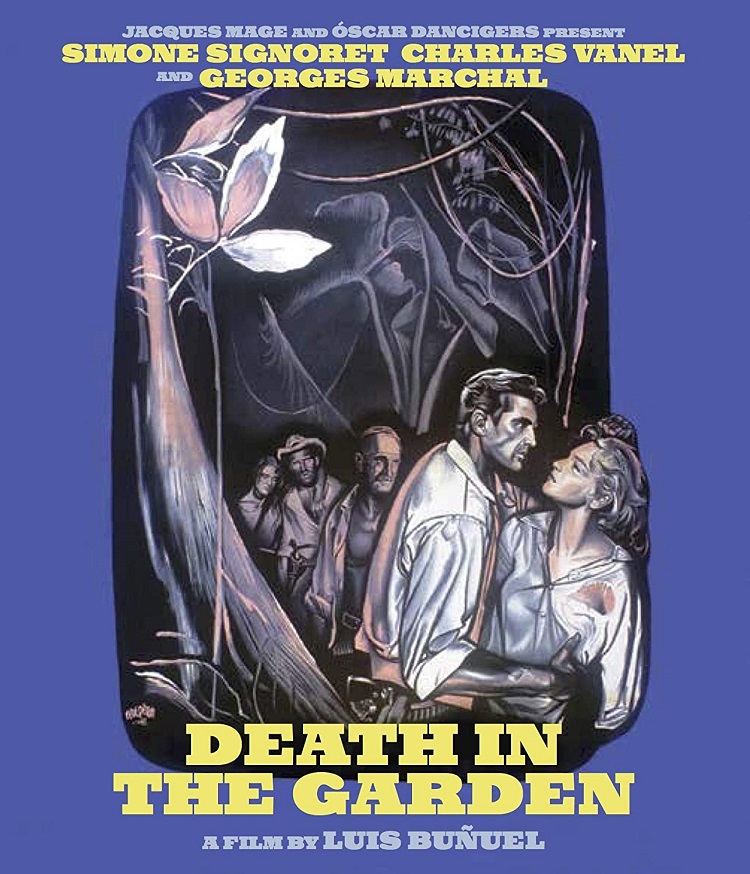

In the mid-’50s, he once again had the opportunity to make films for the international film scene. He made a trio of adventure films dealing with revolutionary subjects, the second of which, Death in the Garden, has now been given a nice high definition release from Kino Lorber.

It begins in a similar fashion to another art-house film from the 1950s, Wages of Fear. In a small, isolated town where a group of strangers tries to eke out an existence amongst a large, corrupt force. Here, instead of an American-owned oil corporation, it is a fascist government in an unnamed South American country, who, as the film begins, takes control of the local gold mine, which is the town’s main source of income. The local citizens and miners stage an uprising and it is this political unrest, much like the unrest that led Buñuel to flee Spain, which is the backdrop to the entire movie.

We meet our heroes, such as they are: Castin (Charles Vanel), an elderly miner who has amassed a small fortune and hopes to move to Paris and open a restaurant; his mute daughter (Michéle Girardon); the hard-hearted prostitute Djin (Simone Signoret); the cynical adventurer Chark (Georges Marchel); and the priest Father Lizzardi (Michel Piccoli). For the first hour of the film, these five characters plot and scheme about how to get out of this town, and how to find some success in life. But as the uprising escalates they each, for reasons all of their own, must flee.

They hire a boat but soon enough the soldiers find them and they escape into the jungle. With a gun in one hand and a machete in the other, Chark leads them deeper into the uncharted territory, escaping the grasp of the soldiers but into unknown horrors. The incessant heat followed by regular showers and the ever-dwindling food drive them to near madness, and yet bounds them together. Eventually, they find a crashed plane filled with canned food, clothes, and jewels. The temporary bond that formed between them just as quickly dies when they are once again afforded some comfort and the possibility of riches.

The priest forcibly removes an expensive-looking necklace out of the hands of the deaf daughter, claiming that it is a sin to steal such things, but then we watch him hide it in a tree. The prostitute puts on a fancy dress and attempts to seduce Chark. Castin has lost his mind and starts shooting up the place. What bonds they found while desperate are immediately destroyed by this surplus of food and supplies.

Buñuel plays it mostly straight but here and there he allows in some of his more surrealistic traits. Like when the snake Chark catches for a meal is instead devoured by ants, causing it to writhe strangely in a closeup. Or when we are transported to the Arc de Triomphe in Paris for a brief moment before the image turns into a postcard that Castin is holding moments before he throws it into a fire.

All of these characters, archetypes one and all, in the hands of another director may have shown eventual signs of humanity, or at least one of them would have found their heart and escaped. But in the hands of Buñuel there is only cynicism and a decisive critique of capitalism, fascism, and the Catholic Church. All stuck within the confines of a genre movie.

I’ve not seen enough of Buñuel’s work to say where this fits inside of his career. It certainly isn’t the surreal visual-scape I’ve heard so many of his early films are nor the more edgy satire of his later films. Death in the Garden is never included amongst his great films (many of which are considered to be some of the best films of all time) but it’s well worth watching and an enjoyable film in its own right.

Kino Lorber presents Death in the Garden with a 1.37:1 aspect ratio and a 1080p transfer. Extras include an audio commentary from critic Samm Deighan, an interview with Tony Rayns who gives some informative background info on Buñuel and his career in Mexico plus the usual trailers and a nice essay in the booklet that comes with it.