In an industry that is lately obsessed with making films available in multiple different versions, both in medium of delivery and in the actual content, it’s astounding to conceive just how disposable film was in its early days. Cinema was more curiosity than art form, and it’s estimated that nearly 75% of all the films made in the early, silent era are lost. There’s a number of reasons for this (not least of which that early film stock, made with silver nitrate, was highly flammable and could even spontaneously combust in the right conditions) but in the end it means that some aspects of the history of film, its development and proliferation, are lost to history.

Which makes all the more amazing a chance discovery in the late ’70s in Dawson City. An old gambling house was being torn down, and the local priest (who happened to own a backhoe) set to digging out the foundations. What he found, amongst the old dirt and concrete, was reel after reel of films. This story is told in Dawson City: Frozen Time, but the documentary is about so much more: the history of the city, the gold rush that led to its unlikely rise and fall (with the consequences for the local tribes and environment, often disastrous) and how that history was intertwined with the rise of the motion picture.

Gold was found in the Yukon in 1896, leading to the gold rush in Dawson City. The population of the town ballooned from 500 into one of nearly 30,000 people. By contrast, even today Dawson City only sports a population of a little under 1800. Many came to mine, and some of the more savvy, in the words of one of a Frozen Time title card, came to “mine the miners” by building stores and centers of entertainment, where the lucky could blow their newly discovered riches and the unlucky could forget their sorrows. Amongst these attractions was a movie house, and eventually more than one. Dawson City, as far north as it was, was the last stop for movies on the distribution channels and would often get its fare years after the movies had played in more populous regions south.

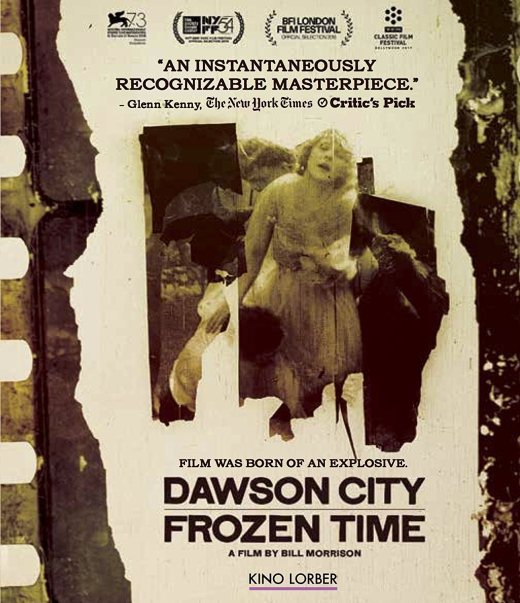

In Dawson City: Frozen Time director Bill Morrison tells this story with a combination of footage, some vintage and some of silent movies that depicted the era, and a number of photographs. There is no narration, only sparse sound effects and the ubiquitous, absorbing score by Alex Sommers, best known for his work with Sigur Ros and for his partnership, both personal and artistic, with that band’s singer, Jonsi. Cannily, the film intersperses documentary photographs and film with thematically relevant clips from silent films, many of them those which were part of the Dawson city find. Many of the photographs are Eric Hegg, whose glass plate negatives were a similar historic find, having been kept in the walls of a house and only discovered when it was being disassembled in 1949.

Exactly where the movies were found and how they ended up being buried underground should be saved for the film, but the theme of only discovering the value of something when it is late, perhaps too late, pervades Dawson City: Frozen Time, as is short sighted-ness. When eventually the man in charge of holding on to the films called the studios to find out what they wanted to do with them, he was told they would not pay for shipping, so the films should be destroyed. Many cans of film were eventually dumped into the Klondike, where so much refuse from the gold prospecting ended up. That adventure was, like so much of life in the late 19th and early 20th century, industrialized, and near the end of the film there’s a vintage overhead shot of the Dawson city area, the terrain for miles scraped into barren waves of sediment by the machines that came, took the gold, and left.

Which may make the film sound like a tendentious political lecture, but it never falls into that trap. The only interviews in the film are of the contemporaries who discovered or helped to restore the eventual treasure trove of old movies found underfoot in Dawson. Most of the story is told in pictures, and words on the screen, letting the viewer draw his own conclusions. Running at just over two hours, Dawson City: Frozen Time is deliberately paced, but the beauty of the visuals and music and the unusual story were fascinating, practically hypnotizing.

The Blu-ray release of Dawson City: Frozen Time comes from Kino Lorber. There are a few extras on the disc, including a short interview with the director, and a nine-minute post-script about the film materials and the archivists who understood their value. Also included is a number of excerpts from the Dawson City Film Find. There is also a booklet with a pair of essays, including an essay about the film by Lawrence Weschler and another about Director Bill Morrison and his other films by Alberto Zambenedetti.