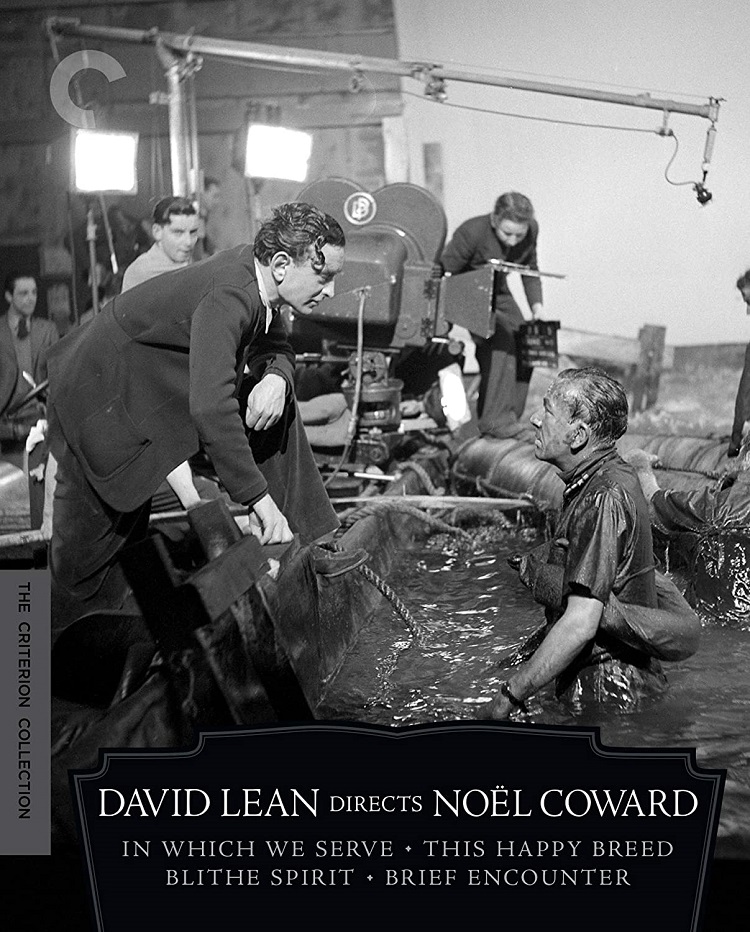

Although best remembered for his widescreen epics such as Lawrence of Arabia, Dr. Zhivago, and The Bridge on the River Kwai, director David Lean launched his feature film career helming a series of fullscreen films written by Noel Coward. Those films have now been compiled in a spectacular new box set from Criterion, providing an engrossing survey of the results of their labors. While clearly not epic in scope, each of the films contain unique delights and are all well worth seeking out.

In Which We Serve (1942) leads off the set and their feature film partnership, and also represents Coward’s most direct involvement with him serving as writer, co-director, and star. The black and white film follows the crew of a British warship as they encounter enemy resistance, abandon their defeated ship, and flash back to their earlier lives as they await rescue while clinging to a lifeboat. Coward plays the captain of the doomed ship and aptly conveys a patriotic fervor and paternal concern for his ship and crew. The other crewmen don’t fully emerge as well-rounded characters, but the flashbacks to their pre-service lives help to enforce the theme of disparate individuals uniting for the common goal of defending their country. The film seems to be mostly a product of its WWII times, and as such doesn’t convey much emotional impact now. However, it is beautifully filmed in black and white and it’s a treat to watch Coward as the dashing captain.

This Happy Breed (1944) begins in the aftermath of World War I and tracks the life of a family through their 20-year residence in a tight-knit English community. The move to color photography seems an odd choice for a film set almost entirely in a drab, cookie-cutter neighborhood, but helps to establish the bleak conformity crushing the spirit of the family’s daughter. Although she’s pursued for years by a handsome young neighbor, she spurns his advances because she believes she’s due more from life. The story checks in with the family every few years, with the conformist parents slowing down with age while their son and daughter explore their horizons, leading to disaster for both of them. Meanwhile, the neighbor boy advances in his military career and makes more of himself than the daughter ever imagined, setting up an inevitable reunion when he throws a lifeline to the wayward woman. Part social commentary, part a study of shifting family dynamics, the film excels at setting a very clearly defined stage and documenting the passage of time on it.

Blithe Spirit (1945) takes a winning departure into comedy and is the most consistently rewarding film of the set. When a wealthy married couple decide to hold a séance at their home for fun, they encounter unexpected results when they accidentally summon the spirit of the husband’s deceased first wife. She’s perfectly happy to be back with the living for the long term, and sets about making the home as unpleasant as possible for the second wife. Only the bemused husband (Rex Harrison) can see the ghost, and Lean mines their comic banter and the second wife’s extreme displeasure for all they’re worth. The already funny premise rises to the next level when the second wife dies and also comes back as a ghost, leaving the husband in the middle of two feuding spirits. The film reminded me quite a bit of the earlier Cary Grant film Topper, with a similar reliance on hilarious, fun-loving ghosts making life miserable for the living.

Brief Encounter (1945) moves back to black and white for a melodramatic tale of forbidden love. A lonely housewife with no passion in her life finds herself falling for a married doctor, with all the ensuing self-loathing and agony it entails. The pair meet at a coffee shop near a train station, with their brief encounters always ending with them departing on trains going in opposite directions, a not-so-subtle metaphor for their lives. With nothing but morality standing in the way of their illicit affair, they fall deeper in love until an impending career move for the doctor forces them to choose a path. The film is reminiscent of any number of Victorian-era novels of forbidden love, with the heroine spending more time worrying about discovery and loss of social standing than savoring her happiness.

Each of the films have been meticulously restored, not by Criterion but instead by the British Film Institute in 2008. They’ve done a remarkable job, with pristine prints that show no evidence of decay. Criterion’s new hi-def digital transfers of those restorations are rock-solid and precise, with no apparent image judder or noise. The black and white films have tremendous contrast, with inky blacks and clear definition, while the color films retain a muted color scheme that appears close to original specifications rather than risking oversaturation. Sound is also crisp and clear on all films, nicely augmented by scores performed by the London Symphony Orchestra for all films.

The DVD bonus features include an array of supplemental information such as a 1971 biography of Lean’s career, a lengthy 1969 recorded conversation between actor Richard Attenborough and Coward, and a 1992 episode of The Southbank Show on the life and career of Coward. I preferred the Lean biography, but the other features are fascinating as well. Each film is presented on an individual disc but housed in a cardstock case with plastic tray, with those cases then combined in a cardstock slipcase, not the ideal archival presentation in my opinion but certainly more eco-friendly than entirely plastic cases.

David Lean Directs Noel Coward is available on Criterion Blu-ray and DVD on March 27th, 2012. For additional information, visit the Criterion website.