Of the spate of Japanese movies that infiltrated the American consciousness at the beginning of the 21st century, when the industry was in a sadly short-lived renaissance, most, like The Ring and The Grudge were by relatively young filmmakers. One, however, was the surprise swan song of a septuagenarian who had been making movies all his life: Battle Royale, directed by Kinji Fukasaku. That’s the movie where naughty schoolkids are sent to an island to do televised battle to the death.

It was also the last film that Fukasaku would make (he died in the middle of directing the sequel, his son taking over) and the end of one of the longer careers in Japanese filmmaking. Any student of Japanese cinema will know that the industry has seen high peaks and deep, deep ravines, commercially speaking. Few directors were able to consistently remain employed from the early ’60s right into the ’90s, but Fukasaku had the instincts to attenuate his talents to the times. Maybe his latter day films tended toward the innocuous, up until the full throated madness of Battle Royale. But for a long run in the ’70s, while many other filmmakers were stuck in programmatic milieus or in making soft core pornography to keep working, Fukasaku launched a wholesale revolution in the Yakuza movie genre.

This started with Battles Without Honor and Humanity, a five film series that examined post-war Yakuza without the rose-tinted glasses and chivalric myths that were the staple of the genre. Those films, which showed ferocious, underhanded tactics and general scumminess of the Yakuza were a sea change in the depiction of Japan’s indigenous crime families, upending genre conventions which would normally depict Yakuza as a kind of nobility once-removed – latter day Samurai in a world that had turned its back on brotherhood and honor.

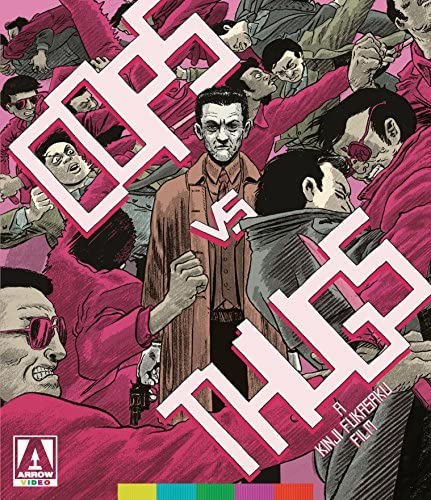

Cops vs. Thugs, which Fukasaku directed between films in his second Battles series, re-unites him the original series screenwriter Kazuo Kasahara. In researching Battles, Kasahara interviewed several Hiroshima gangsters and used their personal stories to fuel his screenplays. Cops vs. Thugs was similarly based of Kasahara’s interviews and observations, this time of the interactions between the Yakuza and the police. Instead of being a straightforward cops vs. robbers story or a tale of police corruption, it reveals a crooked but personalized system of relationships between these two opposed but inextricably linked cadres, and how the modernization of police work, just like the modernization of business, squeezed out the old players but did not necessarily remove the corruption at its heart.

Cops vs. Thugs stars Bunta Sugawara, also the star of all the Battles films, this time cast as a cop, Detective Kuno, who has a tight relationship with interim Yakuza boss Hirotani. Hirotani is trying to keep the family afloat while his boss is in jail. Kuno and Hirotani have a history – the cop kept the yakuza out of jail despite his confessing to a murder, because he liked his manners.

There’s an equanimity between cop and Yakuza. The gangsters drink with the cops, and if they commit some crime that demands somebody be sent to jail, the gangsters will supply a fall guy (usually a volunteer). This is not to say they do not directly conflict, and when a cop decides he hasn’t been properly respected, they can be brutally violent to the Yakuza. This is demonstrated in an interrogation scene that turns into brutal beating, where the gangster is smacked repeatedly, thrown around them room, then stripped naked. Reportedly, the actor playing the Yakuza demanded to really be beaten, which added verisimilitude to the shocking brutality of the scene.

Chaotic brutality is part and parcel of Fukasaku’s film style, particularly when making his Yakuza movies. Scenes of violence are often shot with a handheld, hyper-mobile camera, getting up close to the action, where throngs of men move against each other, throwing blows and whipping out knives. It’s kinetic and engaging, sometimes astonishingly so, when fights that look brutal enough to be real take place in long takes, without cuts or whip pans to hide the action.

What’s less flowing and kinetic is the plot, which feels intentionally murky. There are land deals and family properties being mortgaged in some scheme that’s more eluded to than elucidated: the Kawade gang is making some play, a local politician is playing both sides of the fence, and just when it looks like a gang war is going to break out a new police captain is brought in to clean up the force and put a crackdown on the Yakuza.

Kuno and this new chief Kaida cannot see eye to eye. Kuno and the old cops believe developing a relationship with the Yakuza is the only way to keep peace in town. Kaida believes in going by the book, which means dissolving any ties between the old gangs and the police, and cracking down with brutal force. This does not mean, however, an elimination of corruption in the force.

Ultimately, Cops vs. Thugs is a unique adjunct to the Battles Without Honor and Humanity series. Those intentionally dispelled the myth of the nobility of the Yakuza (without, at the same time, creating heroes out of the police force.) Cops vs. Thugs doesn’t ennoble the Yakuza or return to old clichés, but it does suggest that whatever they were, they belonged to an old Japan that was being stamped out by regimentation and corporatization.

What it maintains is the feel and energy of that series, in particular the action, the humor, the copious violence and nudity. Fukasaku’s ’70s Yakuza movies are filled with, and moved by, ideas but they never forget to be raucous entertainments at the same time. Cops vs. Thugs is about institutional corruption and the anachronism of old concepts of honor in modern Japan, but it’s got large scale gang fights, shoot-outs, a siege on a hotel, some great (and real) car crashes, and everything else you’d want in a Yakuza movie.

Arrow Video’s release of Cops vs Thugs has a good looking print (with the expectation that ’70s Japanese movies are going to look like ’70s Japanese movies – grainy and with largely muted colors.) The extras are pretty light on this release. Unfortunately (as is pointed out in the print essay accompanying the film) the filmmakers and actors in these films are rapidly dying off, so they just aren’t around to get interviews from. On the disc, there’s a short conversation about Fukasaku’s Yakuza movies by his biographer Sadao Yamana, a contextual video essay by Japanese film expert Tom Mes, and a fun but awfully brief (less than five minutes) bit of behind-the-scenes footage of Fukasaku during the making of Cops vs. Thugs, which include him discussing his purpose behind the film, then a couple of minutes of rehearsal footage of the brutal interrogation scene. Interesting, but the real attraction of this release is the film itself: tough, brutal, and a welcome addition to the growing collection of Fukasaku work available on Blu-ray.