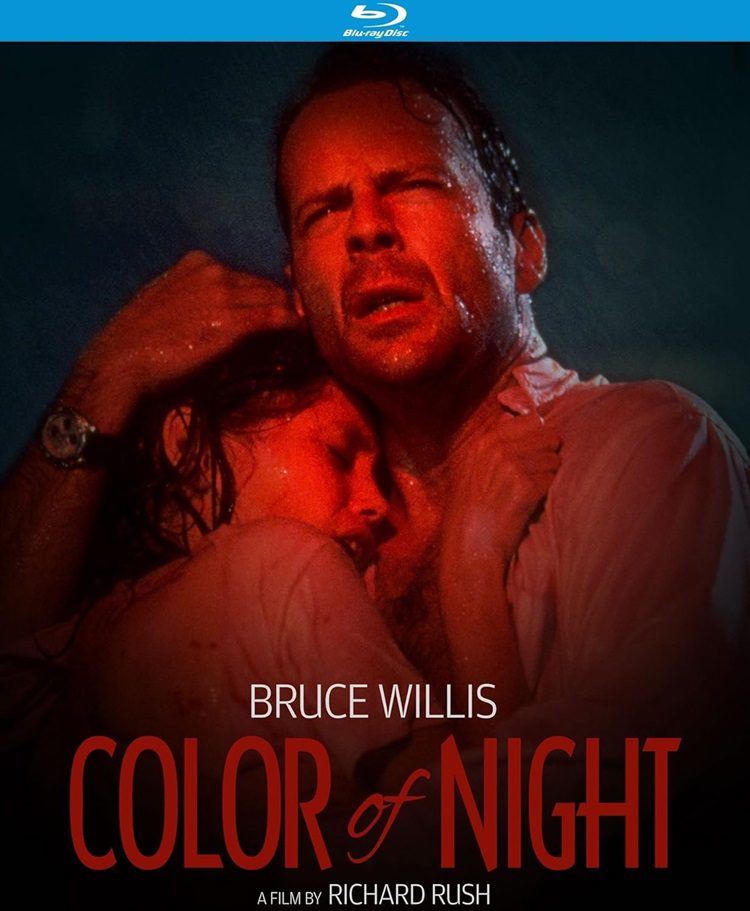

Much like director Richard Rush’s 1980 cult classic The Stunt Man has never been the sort of film one could easily classify under just one genre, his following feature Color of Night isn’t a movie anyone can describe as being merely “good” or “bad.” For it is both of these things, and yet, neither. As unforgivably ’90s as you could possibly ever hope to get, Color of Night is an unbelievably goofy psychological thriller with a heavy focus on sex ‒ and very little else.

Making little to no sense throughout the bulk of its two-hour-plus runtime, Color of Night finds a pre-Pulp Fiction Bruce Willis ‒ uncertain where his career was after the box-office bombs that were Hudson Hawk and The Last Boy Scout ‒ as a psychiatrist who has an issue with the color red (which, when viewed today, causes one to wonder if even M. Night Shyamalan’s one and only “good” film was just a con job); as we witness in the opening of the film when a suicidal patient (Kathleen Wilhoite) leaps out of his top-story office with the nice big street-facing window right onto the pavement below.

Needless to say, this puts Willis’ Dr. Bill Capa in a deep state of depression. But it’s somewhat difficult to discern all of that, since it’s Bruce Willis we’re talking about. The fact that Color of Night features what I personally felt was Dominic (The Outer Limits) Frontiere’s weakest score, as well as a laughably bad theme song ‒ “The Color of the Night” ‒ by Lauren Christy only add to the unintentional charm.

Fortunately, that all changes once “Dr. Billis” jets off to sunny Southern California to visit his good friend (and fellow psychiatrist), Dr. Bob Moore. The latter is played by a freshly out-of-work Scott Bakula, whose award-winning series Quantum Leap had only ended the year before. Bob welcomes Bill into his group therapy session ‒ which is where one of the true genuine pleasures of the film can be obtained, for the ragtag motley crew of neurotics are brought to eccentric life by a nymphomaniac Lesley Ann Warren along with three of the greatest character-actor heavies to ever hail from the ’90s: Lance Henriksen, Brad Dourif, and Kevin J. O’Connor.

While the invite seems harmless enough, Bill soon learns Bob believes one of his the nutjobs wants to kill him; something which actually happens before Bill gets a chance to get his feet wet. At the behest of a belittling, foul-mouthed police detective (Ruben Blades, who serves as comic relief in an entire movie that serves as comic relief), Bill takes over the session to out the killer. Bill also takes over living in Bob’s shoes, inviting a cute little spinner named Rose (Jane March) to come and go, but mostly come, since multiple steamy sex scenes were part of our stars’ contractual obligations ‒ to say nothing of customary for any erotic thriller produced in the ’90s.

But unlike similarly themed titles of the era, most of which were released direct-to-video, Freebie and the Bean director Rush was determined to crank up the heat for what would prove to be his first directorial effort in nearly 14 years. He wasn’t alone, either: purportedly, Mr. Willis himself unclad his member for his various interactions with Ms. March, before said part was snipped out of the finished work (any and all puns intended).

This leads us to the epicenter of Color of Night‘s long-lasting infamy: its various cuts. Richard Rush delivered his cut of the film to producer Andrew Vajna ‒ the prolific Hungarian-American film backer who brought us First Blood, Total Recall, Tombstone, and Die Hard with a Vengeance‒ in late 1993, only to have the famous producer demand it be recut. This beget a (then) well-publicized skirmish between the two over who should have final cut; a feud which escalated as Vajna attempted to fire Rush, prompting the Director’s Guild to intervene. The stress proved too powerful, however, culminating in Rush suffering a near-fatal heart attack.

Amidst Rush’s recuperation, he and Vajna ultimately decided the Producer’s Cut would debut theatrically in August of ’94, under the condition the director’s original version would find its way to home video afterward. In an almost fitting twist of fate, Vajna’s edit was one of the most critically panned films of 1994; the Rush cut became one of the hottest video rentals of 1995. Some time later, Maxim magazine stated Color of Night featured the hottest sex scene in cinema ever. Eventually, the infamous Theatrical Cut all but vanished in the shadow of the “preferred” Director’s Cut ‒ as the former muddy vision never found its way to home video.

Until Kino Lorber picked up the title for distribution, that is. A much-needed upgrade to the old budget release from Mill Creek Entertainment, Kino’s two-disc Special Edition, Kino’s release of Color of Night brings us both cuts the much maligned (but so amusingly enjoyable) erotic thriller for all to see (and maybe scratch their heads over a bit). Needless to say, the differences between the two versions are like Night and day: Vajna’s edit is slim on exposition, heavy on dumb; Rush’s vision throws in a lot of (odd) comedy, and attempts to explain the inherent silliness, but, that said, it’s still a pretty dumb movie. Then again, that’s what’s fans of the film enjoy about it!

Both versions receive MPEG-4 AVC 1080p encodes and preserve the intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. Ironically, Vajna’s 122-minute version is the best-looking of the two, as it was essentially locked away somewhere when everyone realized what a turkey it was. Rush’s 140-minute cut, on the other hand, was already rough around the edges when it debuted on home video due to the lack of care exercised while the editing war was in motion. The result here is essentially less crisp, less clear, and less Color. While it’s a bit of a pity Kino didn’t think to incorporate the superior video from the Theatrical Cut into the Director’s Cut to make a composite, I’ll take it either way.

Aurally, each version includes DTS-HD MA 5.1 and 2.0 audio selections, while only the Director’s Cut features optional English (SDH) subtitles for some reason. Both cuts sport an audio commentary for your heightened enjoyment: the Theatrical Cut features screenwriter Matthew Chapman at the helm (as moderated by Heather Buckley), the Director’s Cut includes a new recording of Richard Rush, who is joined for the session by Elijah Drenner. Additional supplemental materials for this two-disc set from Kino Lorber consist of an animated gallery on Disc One, and ‒ strangely enough ‒ the theatrical trailer on the Director’s Cut disc.

It doesn’t make a whole lot of sense, I know. But then again, neither does Color of Night in any shape or form, so just sit back, turn off your brain as best you can, and enjoy this, one of the greatest bad erotic thrillers from the mid ’90s.