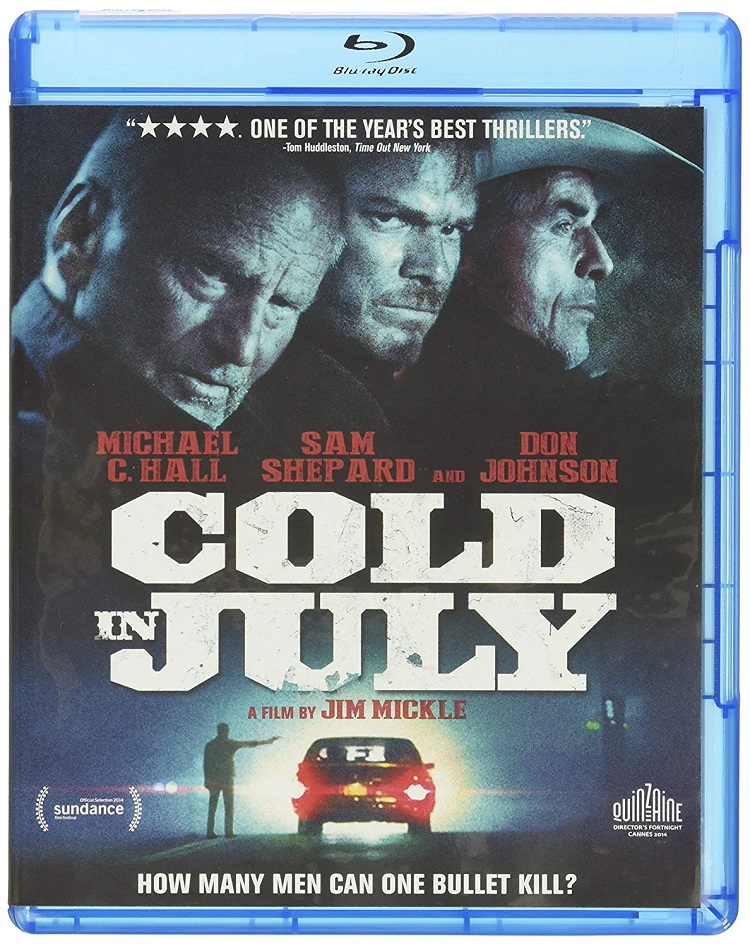

I never thought I’d be typing these words, and please believe me when I write that this is not a backhanded compliment: Don Johnson is the best thing in Cold in July. Playing a large-living private investigator who drives a fire-engine-red Cadillac with longhorns attached to the grille (the film takes place in 1978 Texas, ‘nuff said), Johnson struts into the story about 30 minutes in and provides some much-needed vigor and comic relief.

Unfortunately, Johnson’s entrance is also where the film itself takes the first of several seriously warped turns. The plot is kicked off when suburban family man Richard Dane (Michael C. Hall of TV’s Six Feet Under and Dexter) accidentally kills a nighttime intruder who, it turns out, was unarmed. Shaken and feeling guilty, Dane, his wife (Vinessa Shaw) and young son are soon being terrorized by the intruder’s violent ex-con dad Ben Russell (Sam Shepard), who is seeking revenge for the killing of a son he himself barely knew.

Hall does well by the character in these early scenes. Dane has apparently been kind of a wimp up until now, but after what’s seen as a totally justified shooting (a real Texas man stepping up to protect his home), he’s disgusted but perhaps also a tad cocky when his neighbors start to treat him with a mixture of fear and respect. So far, the film has been a tense, well-done procedural along the lines of Cape Fear; credit to director and co-writer Jim Mickle for knowing how to stage and edit a suspenseful scene or two.

However, when Dane begins to suspect that all is not as it seems and that the cops have been playing both him and the elder Russell, Cold in July starts down its road as an ever-more-twisted film noir, uneasily combining vigilante justice, Oedipal conflicts, and snuff porn. I would try to detail more of the plot but it’s so riddled with inconsistencies and blind alleys that I’m not sure I understand what happened, let alone why.

Let me make it clear that I don’t think every film has to have an A-B-C plot and clearly stated motivations to be enjoyable; in fact, the opposite is more often true. But Cold in July‘s complications aren’t in the service of anything except moving us toward a hyper-violent shootout/bloodbath finale. I’m also not opposed to violence in movies per se; in the hands of a Tarantino, a Scorsese, or the Coen brothers it can be disturbing, yes, but also comic, poetic, socially relevant, and just plain good scary fun. But Mickle and co-writer Nick Damici seem to be piling up the bodies simply for shock’s sake, which left me feeling queasy, sad. and angry.

At first, Johnson’s PI provides a voice of sanity and world-weary cynicism; he’s particularly funny using a very early-model cell phone that’s the size of a shoebox. But he too succumbs to the plot’s craziness, propelled by the taciturn and appropriately scary Shepard.

Hall is quite a good actor, and the guy who was able to make serial killer Dexter a quasi-likeable character might have been able to take us along on Dane’s journey from ordinary guy to avenging angel. It’s somewhat plausible that his initial act of violence jarred him loose from his safe suburban existence and into a dark world, but after a while his actions play as either idiotic or over-the-top unhinged, while his affect remains steadily glum. Perhaps all this is clearer in the Joe R. Lansdale novel the film is based on (I haven’t read it), where we might be privy to Dane’s inner thoughts, but the film leaves us on the outside looking in. After 109 minutes of this, Cold in July left me cold.

Cold in July opens theatrically and on VOD May 23.