As a masterpiece, Chinatown needed its two main creators, screenwriter Robert Towne (who won the movie’s sole Oscar) and director Roman Polanski. Of course, many of us regard Chinatown as the Great American Screenplay. But its uncredited co-writer is Polanski. Without his bleak editorial touch, the movie wouldn’t have been as focused or tight. It wouldn’t have reached the pantheon.

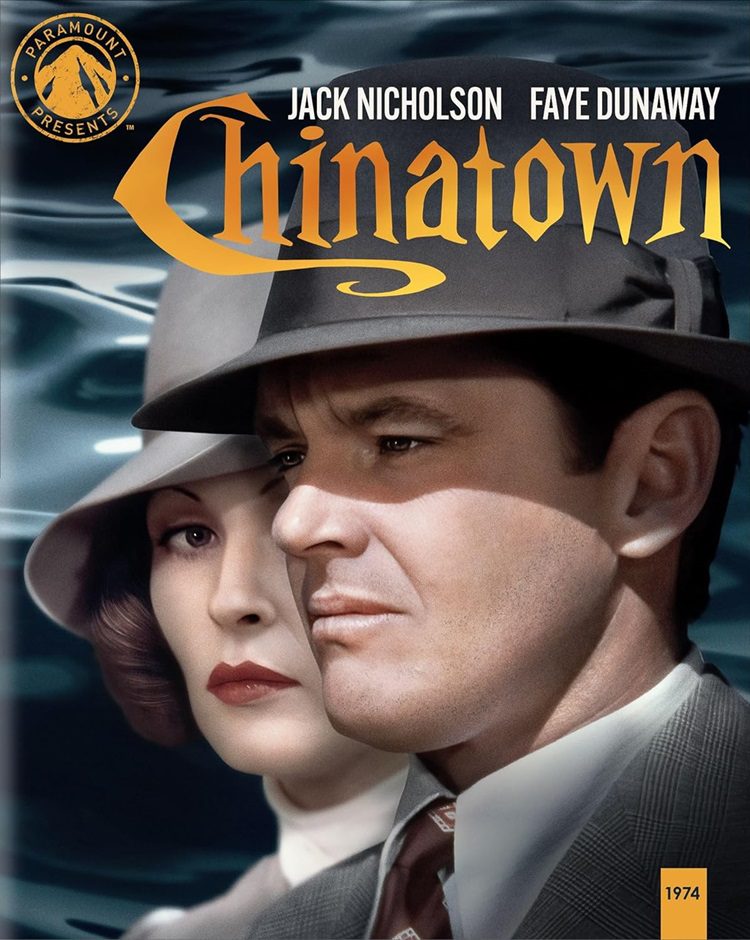

Buy Chinatown 4K UHDI won’t recite the plot. Yes, the movie’s dense. Yes, it’s about a dapper private eye, J.J. ‘Jake’ Gittes (Jack Nicholson). In 1937 L.A., Jake works a case that involves a public water scandal and a mysterious socialite, Evelyn Mulwray (Faye Dunaway). When her husband dies in a so-called drowning, Evelyn hires Jake. If only he knew what lay ahead.

Chinatown tips a fedora to the mystery fiction of Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, to film noir. Still, the movie surpasses being a simple tribute. It doesn’t ape the noir classics that preceded it. It’s after a more modern sensibility.

Polanski’s team nail the look and feel of this world. They’re working at the peak of their powers. John Alonzo’s rich, gleaming cinematography stuns, as does Jerry Goldsmith’s sad, trumpet-driven score. Dick Sylbert’s production design is a model of purpose and precision in creating a near-seamless reproduction of the past. Anthea Sylbert’s matchless costumes help fill the space.

Nicholson shines. We’re used to Jack the clown, the outsized, over-the-top personality who can border on self-parody. Each time I see Chinatown, though, I forget it’s him. It’s Jake. Subtly, Nicholson shows the character think. Dunaway, too, is unforgettable. Her portrayal of Evelyn is a masterclass in how a reserved, even chilly neurotic can unravel before our eyes, baring her vulnerability. As her father Noah Cross, John Huston radiates an evil, beady-eyed charm—what a brilliant touch it was to cast the deep-voiced bear.

Chinatown remains singular. Not only for its talent, though, or how it plays with the noir mold.

So many colorful choices abound. We see how hard Jake works; how tedious his job can be, the ploys he’ll pull (such as when he wishes to meet with a public utilities head or needs a copy of deed ownership). Detecting for him requires craftiness, practicality, and even boldness. Nosiness. I love the realism of the nose bandages he wears for a chunk of the film. I love the way Noah Cross never gets Gittes’s name right. And I love how the past plays a prominent role in the story, yet the movie never subjects us to flashbacks or tiring exposition. Wisely, the filmmakers don’t show us everything. We get a taste of Jake’s past, just enough to drive the story forward. Set in L.A.’s Chinatown, the famous climax depicts the illogical but true reality of the place (as the film conceives it) as a state of mind.

This Chinatown-as-central-metaphor is key. More than the cleverness, the intricacy of the plot, or the talent involved, the movie’s vision—a sun-choked but dark-as-night detective thriller with full-bodied characters, that’s about total corruption and (as Towne called it) the futility of good intentions—gives it heft. The movie floors this concept. The concept is the spine.

Jake is an excellent operator. He’s a cynic who, because he specializes in ‘discreet investigations,’ trucks with touchy women and men; but he’s nobody’s cliché of the hard-boiled, tough-talking dick. He’s a nice guy with a certain code. He can be a gentleman and kick ass. You can bullshit him, but he’ll see right through it. And yet. In Chinatown, he’s in over his head. He wants straightforward answers, but everything’s a fog. Eventually, he can know what’s happening. But it doesn’t matter. Once he finds his footing, it’s clear his work is a waste of effort. The villain triumphs. He walks away scot-free. Justice does not prevail. Jake loses big.

A gorgeous dame with a shameful secret and sham poise, Evelyn lures him into a web of deceit. But she’s not malicious. She’s just trying to survive. Her cover won’t hold. She’s out of her depth navigating the tricky circumstances that arise. And like Jake, she’s lonely. At first, we might think her a classic femme fatale, the typical enchanter in film noir who’s a bearer of bad luck. Way more trickles under the surface. L.A., a false Eden, shares a similar fate. As a city, it is eggshell-fragile. It, too, is phony—a distressed front. To keep up appearances and sustain the lives of the dreamers and exiles who call it home, it needs a mess of love and care (i.e., water) to function.

Chinatown, then, focuses on illusion and contradiction—on the flaw in Evelyn’s iris. It’s about powerlessness in the face of powerful evil and ruin. The movie offers a clear but grim view. It’s a beautiful bummer, one that (aside from its droll moments) insists that everything is fucked. This sensibility, of course, is apropos of a movie from the paranoid ‘70s. But Chinatown‘s pull and impact take it beyond a well-made detective thriller with fine performances. (One joy of rewatching Chinatown lies in tracing the scattered clues.) It’s among our best American films because it’s a superb entertainment about lost and lonely, lovable characters we care about. It’s a broken puzzle about broken people.

And it’s a glimpse of a lost world. Paramount Pictures created Chinatown during a time when the buildings and cultural artifacts of the era it depicts still existed. Sure, many a film offers a similar portal; but Chinatown’s scrupulous recreation warms the heart of this native Angelino.

Thanks to Polanski, the movie embraces the darkness at its core. Polanski made other, later films of note. But he strikes me as complacent. Seldom has he shown the sure, hungry hand he did in Chinatown. Tragedy mars his life, and I’m no apologist. But Chinatown was, after a period of drift in Europe (and before he became a fugitive), a chance to show the New Hollywood crowd that Rosemary’s Baby (1968) was no fluke. That he could be a Hollywood powerhouse. He delivered. Chinatown (for my money) is his last true hurrah.

It’s a miracle this movie exists.

As part of its ‘Paramount Presents’ line, Paramount has released a new limited edition 4K UHD set of Chinatown. The 4K picture and audio are stellar. It surprised me to see that this release includes a second disc, a Blu-ray of the much-maligned sequel, The Two Jakes. (It’s fun on its own stinky terms.) Among the special features included on the 4K disc is a new appreciation of Chinatown by Sam Wasson, author of The Big Goodbye, a splendid book about the film’s production. Other features include older commentary by Towne and director David Fincher, plus mini-documentaries about the movie’s history and legacy. You also get access to a digital copy of the film.