If you were to say I would love to see a Technicolor noir western directed by Jacques Tourneur, set in Oregon, I would say you are darn tootin.’ I would love to see it and see it I did.

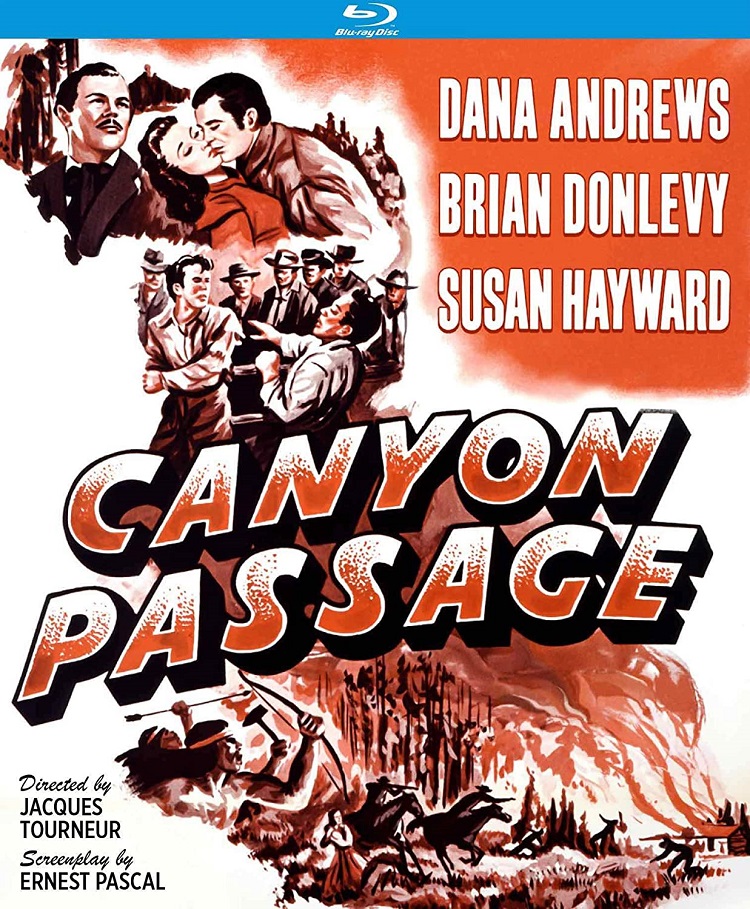

Canyon Passage (1946) is that rarest of things: a good art western disguised as a B-movie, buckling at the seams to beat the revisionist wave of westerns by about twenty cool years.

But of course—no such motive existed.

Rather, Tourneur delivered a crisp, 92-minute oater that combines several genre elements. Rape, poker, murder, lust for gold, love triangles, Indian attacks, cabin-raisings, bar brawls—they are all here.

Where Canyon Passage excels though—like it belongs in more jaded company—is its relatively stark depiction of a frontier town on edge. Tourneur’s film is not so much a quest story as it is a diagram on how Jacksonville, Oregon in 1856 might assume a state of civilization.

The three leads, pack-mule express owner Logan Steele (Dana Andrews), banker George Camrose (Brian Donlevy), and Lucy Overmire (Susan Hayward), anchor us. George is engaged to Lucy, who goes with Logan on their way home to Jacksonville. Despite George’s claim on her, Lucy seems more in love with Logan, who might reciprocate but courts another girl in town. Logan will not betray George. A compulsive gambler who bets the gold dust to which he is entrusted, George is a close friend.

Surrounding our uneasy trio are random, inevitable agents of chaos: potentially crippling games of chance at Lestrade’s gambling den; the shadowy pine forest and jagged cliffs; the Indians who want their land back; Bragg (a leering and amazing Ward Bond), a burly figure of id whose appetite for sex and violence makes him, and all who oppose him, an easy target.

Torn between rambling and putting up roots, Logan embodies the film’s curiosity. Not only does he refuse to betray a friend, he will pay that friend’s debts. He also does not seem to care much about defending his honor, until the other men in town practically demand he fight Bragg. Nor is Logan a weakling—he is strong, unafraid to use his gun, or his fists, but only if he must.

Tourneur draws the other leads with this same depth. These are adults, overly witty perhaps—and that quality derives from being actors of their time, looking and sounding like they just flew in from the Rainbow Room and spent two hours in makeup and hairdressing. But Tourneur digs the ambiguity. Every major character has an angle, has a little (or, a lot of) darkness in them; and only a “thin margin” keeps them, and Jacksonville as a whole, from imploding.

By no means is this a perfect film. The cinematography is a wonder, as is the lived-in production design. I especially like the way parts of Jacksonville seem built at choppy inclines, as though we are witness to a town birthing itself in a barely tamed wilderness. In every interior there is some detail, some rustic-looking article, which conveys the level to which the filmmakers want to present a town composed of hand-me-downs and pine.

The bar fight between Logan and Bragg is a doozy, too. By today’s standards, it is tame, but the way Tourneur builds and edits this scene makes it a taut classic of its kind.

I applaud Tourneur for wrapping his curiosity about the human condition—about the way a nascent community coheres (and threatens to fall apart)—in a tight B-movie package. Because Canyon Passage is pre-ratings system, much of the violence happens offscreen; but seen or suggested, it is brutal, imbuing the red and green hues onscreen with a certain logic and mood.

Compared, however, to a beautiful, big-budget fiasco like Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1981)—a film that should have hewed closer to the matinee thrills and spills of old-time B-movie westerns—Canyon Passage is quick, almost too quick, about the business on its mind. Not for one second, really, does it slow down to exult in the beauty of each frame, or to ponder the folly of these settlers trying to ward off the darker forces (within and without) that would do them in. This modesty is part of the movie’s charm, just as it prevents the film from diving deeper into backstory and intent.

But action should be character—I am not sure I want more time to absorb the turns of the plot. I think Tourneur’s main concern, his actual gift, was to build and sustain a mood. To give texture—a peculiar, almost distancing sort of texture, with the characters rarely shown in close-up, or as mere symbolic props in a morality play (or, for that matter, in an overt play on the viewer’s sympathies—like I said, there is both darkness and light in some of the roles; Tourneur seems to reserve judgment except to imply that everyone, friend or foe, has an innate right to do as they will and try to survive [consider Andy Devine’s summing-up, after Indians interrupt the cabin-raising]). To this end, Tourneur succeeds. Wildly.

Some of the narrative choices, though, feel a bit cheap:

Hoagy Carmichael plays Hi Linnet, a wandering minstrel, a one-man Greek chorus. In profile, he is very much that guy—the observant beanpole with mandolin and mule, loping from one edge of town to the next. Virtually omnipresent. Reporter and spectator. Cipher. Allowing the viewer to see and hear things only he might be privy to.

Besides adding atmospheric relish, Carmichael’s presence counts for little. Producer Walter Wanger may have thought it jake to give him more than just a walk-on part; to have him add flavor and flair by singing some songs. Said songs are pleasant enough; they do not abruptly stop the story in its tracks. As it is, though, Linnet seems about as consequential a character as John Hurt’s Billy does in Heaven’s Gate, or as Bob Dylan’s Alias does in Sam Peckinpah’s over- (and under-) rated Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973). He is a knowing jester that links the leads to the town, to the viewer, and…that is all.

You could argue that Hi Linnet fits the movie’s design; that he is a conduit for the director to be “the camera eye,” passively watching the action he depicts. But I do not buy that. Cynicism, doubt, loyalty: of things said and left unsaid, Tourneur and co. display much of the tension without a need for Carmichael to be there.

I could also quibble about the anticlimactic way we learn about George Camrose’s death. He is an unlikable guy, but he grows on you. He inspires mixed feelings. When a townie (Lloyd Bridges, in the very pink of health, and a ringer for a young Ryan Gosling) tells Logan what happened, it has the effect of dropping on the ground a road apple the size of an anvil. Tourneur should have found a more graceful way to convey the character’s demise. As it is, this development feels rushed and forced. It’s lazy.

Canyon Passage is easy to enjoy, though. A stylish gun for hire, Tourneur was a master craftsman who rarely, if ever, hopped on his soapbox so hard he face-planted; and from what I can tell he never made big splashy “A” films.

Look at his credits. Made and released just after Canyon Passage, Out of the Past (1947) is one of the best film noirs. We also have Tourneur to thank for some of the most fruitful and frightening Val Lewton productions—Cat People (1942), I Walked with a Zombie (1943), The Leopard Man (1943). He also went on to do Night of the Demon (1957) and an episode of The Twilight Zone, “Night Call” (1963), further cementing his status as one of the all-time great directors of the macabre. These titles only scratch the surface of his filmography.

Recently, the Criterion Channel had Stars in My Crown (1950) available to stream. It is one of Tourneur’s most gentle efforts, a feel-good but dramatically satisfying companion piece to Canyon Passage that is among the more memorable sagebrush melodramas outside of the John Ford canon. I highly recommend it.

Canyon Passage, lovingly preserved on Blu-ray by Kino Lorber, is only slightly less distinctive than some of these credits (this could be due partly to the horror films’ highly suggestive sense of dread and the impression they made on me as a youngster). You would be hard-pressed, however, to find a more atmospheric and piney western from the 1940s.

Come for the action and scenery. Stay for, and study, the way the director uses a sense of place to inform the way he dramatizes a group of pioneers.

The Kino Blu-ray is light on features. The disc sports the theatrical trailer, and Film Historian Toby Roan supplies audio commentary.