Every era gets the horror monsters it deserves, I think. In the ’30s and ’40s old literary monsters were brought to cinema in the form of the Universal classics: Dracula, Frankenstein, and movies beyond, with one foot in the present and one in the past. The time periods of the movies were always vague – main characters dressed relatively contemporaneously, but somehow lived in ambiguously ethnic European villages. The lord of the manor may wear a modern suit, but the peasants next door had lederhosen, torches, and pitchforks always at the ready. Modern horror revolves around zombies or haunted houses (subtextually, modern comforts are an illusion that are no protection against the real dangers in life, and in fact make us helpless when pitted against them.)

In the ’50s, nuclear horrors held sway, and the monster, either an alien invading earth or a side-effect creation of the terrors of the atomic age was king. These were movies where, instead of tombs and misty moors, horror was found in laboratories and shuttle launches. It was in this context that one of the earlier Italian forays into science-fiction horror was produced: Caltiki the Immortal Monster.

Starring a Canadian who lived in England, an Italian bombshell with an Irish stage name, and a German playing the human antagonist, Caltiki was shot in Italy and so, naturally, set in Mexico. This was to take advantage of the Mayan pedigree of the story. The historical Mayan disappearance is central to the film’s mythos. Our hero John Fielding (not a Mexican) is on an archeological dig with several colleagues when they discover the tomb of the mysterious Mayan goddess Caltiki. Several members of the expedition are killed when, from these ruins, a blob-like monster emerges from an ancient pit. Fielding, as level-headed as any of the explorers in Prometheus, sets the whole damn thing on fire and runs away.

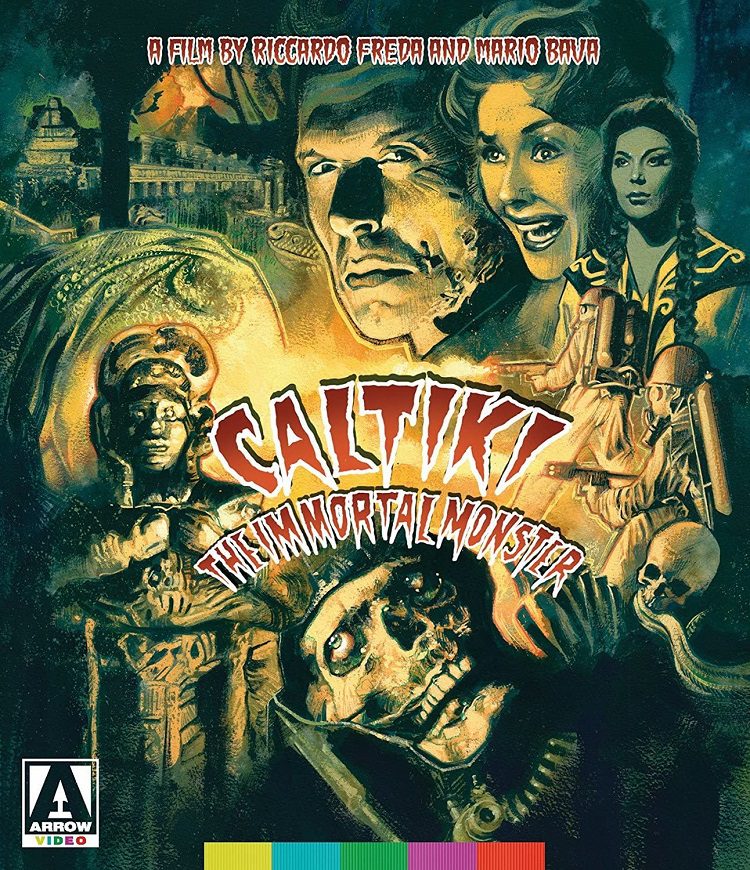

Except that part of the creature is attached to his partner Max Gunther’s arm. In one of several impressive gore shots (especially for the time), the creature is rolled away from the arm, revealing a fleshy mass of eaten skin and exposed bone. This is a remarkably grisly shot, and one of the many contributions to the film, whose credited director is Riccardo Freda, of Mario Bava, who was the special effects director, as well as the film’s cinematographer.

For Italian movie buffs, the story behind the camera may be more interesting than what’s on screen. Freda was a friend and colleague of Bava’s who decided to essentially force Bava into directing by abandoning the film with weeks of shooting left to go. Bava completed the movie, and thus was able to move into credited directing, at the young age of 45. The exact machinations that happened behind the scenes are detailed in extensive extras on this Arrow Video Blu-ray, which includes an appreciation of the movie by British cinema expert Kim Newman, and several Italian featurettes.

But tempting as it is to look at this movie as just a historical cinematic artifact, that would give short shrift to what happens on-screen. Because while Caltiki may follow well-trodden paths with elements borrowed from American and English science-fiction monster movies, what bears noticing is how damn well made this silly little movie is. For one thing, Caltiki moves. There is, short of a rather silly Caribbean dance scene that has no place in a movie set in Mexico, very little fat in Caltiki‘s 76-minute running time. It is not paced relentlessly like a modern action movie, but with lean efficiency. Every scene lasts just long enough to have its full impact, and not a second longer, and the movie still has time to mesh themes about cosmic horror, greed and obsessive love, police chases, car chases, jailbreaks, children in peril, and enormous blobs of goo eating a house.

None of the characters are particularly memorable (that is rarely the point of this kind of movie) but fulfill their on-screen jobs without being embarrassing or irritating, which is enough. Gerard Herter’s Max Gunther probably makes the strongest impression, since his character is an amoral rat. He gets attacked by the creature by coming too close, trying to collect stolen gold from the tomb. As the thing takes over his mind, it turns him from a mild miscreant to an unrepentant killer.

But the big star is, undoubtedly, Caltiki herself. In the story it is a unicellular organism that, when bombarded with certain kinds of radiation grows exponentially, and feeds on everything in its path. On film, it looks like a giant blob of writhing flesh. While the audience does have to do some work suspending their disbelief, it never feels ridiculous. It always manages to look slimy and writhing and kind of alive. These special effects, and the more invisible but no less important matte painting tricks which create the vast Mayan tombs the archaeologists explore, were all created by Bava, and are memorable in a genre and era where monsters are mostly good for a laugh.

There is a fun mix of the old and the new world in Caltiki, which has in more recent assessments led reviewers to identify Lovecraftian elements. Caltiki and Cthulhu aren’t so far apart, lexically. But Bava didn’t write the script, which was written by Filippo Sanjust (who also was a set designer) and he didn’t direct the dramatic scenes, that was credited director Riccardo Freda. But between these three creators they have crafted a decidedly entertaining film. Calling Caltiki a lost masterpiece wouldn’t make sense – it doesn’t strive for that. It strives to be a lean thrill-packed monster movie, and mightily succeeds.

Caltiki the Immortal Monster is an Arrow Video release, and is completely packed with extras. Two versions of the film are on disc – the standard film in 1.66:1 aspect ratio, and also a transfer with mattes removed in 1.33:1. Bava’s special effects shots were done in this aspect ratio, and then matted when they were edited into the film. There are two commentaries by different Bava scholars (Tim Lucas and Troy Howarth) which are both worth listening to for their information on the production and the historical context of Caltiki in Italian cinema. The film contains both English and Italian audio (both are dubbed.) Besides the Kim Newman video discussion mentioned above, there are some interview with Italian critics about Caltiki and Italian genre films in general.