After spending its first act setting up a rote narcotics syndicate narrative — freshened ever so slightly by cattle hormones acting as the illicit product — Michael R. Roskam’s Bullhead takes a turn for the intimate. Abandoning the finer details of its cop-killing conspiracy plot, the film homes in on the inner life of hulking Belgian cattle farmer Jacky Vanmarsenille (Matthias Schoenaerts) and seems to promise some grand insight into his steroid-addled, belligerent character. Roskam would’ve been better off sticking to clichéd drug plotting.

Bullhead, nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, takes a turn toward the unbearable with a mid-film flashback that reveals a disturbing moment in Jacky’s childhood at the hands of a cruel bully. The blunt literalism of his injuries is presented as a crucial element to understanding his persistent inferiority complex and out-of-control machismo. Trouble is, this kind of obvious psychologizing reduces Jacky to his one defining characteristic (or in this case, the lack of it), and from here, it’s nearly impossible for the film to offer any true insight into his actions, which don’t deviate in the slightest from preconceived notions of raging masculinity.

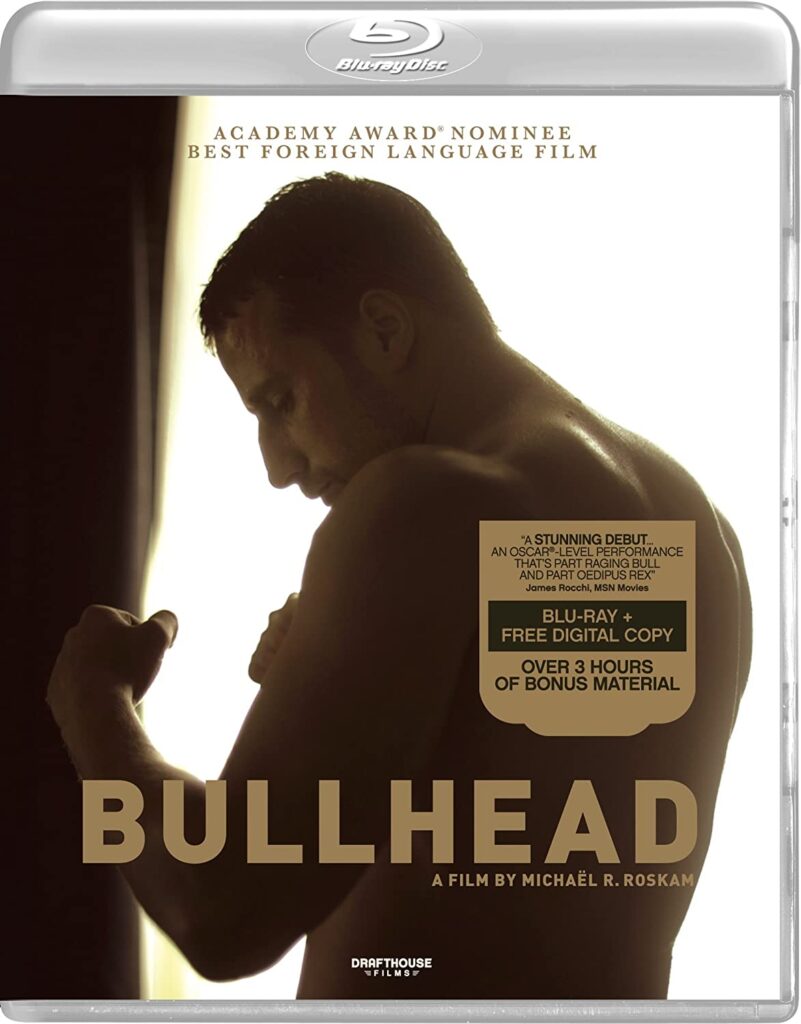

That’s too bad — while the film frames him almost entirely in terms of his sinewy physicality (shot after shot of bulging muscles glinting in refracted light), Schoenaerts possesses a modicum of vulnerability that gives us a better glimpse into Jacky’s interior life than Roskam’s screenplay ever does. His clumsy pursuit of a childhood crush (Jeanne Dandoy) and his tentative reconciliation with a former friend (Jeroen Perceval) — both of whom were critical parties in his past trauma –allow opportunities for Jacky to seem almost human.

Ultimately though, that’s not in the cards — Roskam can’t resist the central man/meat metaphor at the heart of the film. Cross-cutting between a herd of tightly packed cattle, pumped up on growth steroids and the similarly juiced Jacky, the character is reduced to a large slab of flesh. Somehow, Bullhead sees this comparison as indicative of the character’s tragic nature, and the film’s absurdly heightened conclusion confirms the operatic aspirations.

All of this sound and fury distracts from the fundamental shoddiness of the screenplay — scenes are strung together with little connection, and the hormone-trafficking subplot turns out to be mostly clutter. But even with tidier construction, Bullhead’s ham-fisted characterization would ensure it’s about as meat-headed as Jacky himself.