Hayao Miyazaki’s downbeat personal sensibility, constant self-doubt, and pessimism are nearly absent from his works. My Neighbor Totoro, Kiki’s Delivery Service, and Spirited Away are all populated by young people who, despite their personal problems, eventually do their best. Princess Mononoke is graphically violent and depicts an intractable conflict that leads to much death and suffering, but it ends with at least the possibility of reconciliation.

Miyazaki’s best work (which include most of his feature films) are palpable with this sense of tension – that the world is hard and full of problems, and that if they can’t be surmounted, they can at least be understood. That he does this while never, ever losing a sense of story and entertainment is what creates his genius. His endlessly entertaining films come not from a reproduction of successful formula but from a genuine expression of the contradictions in his heart.

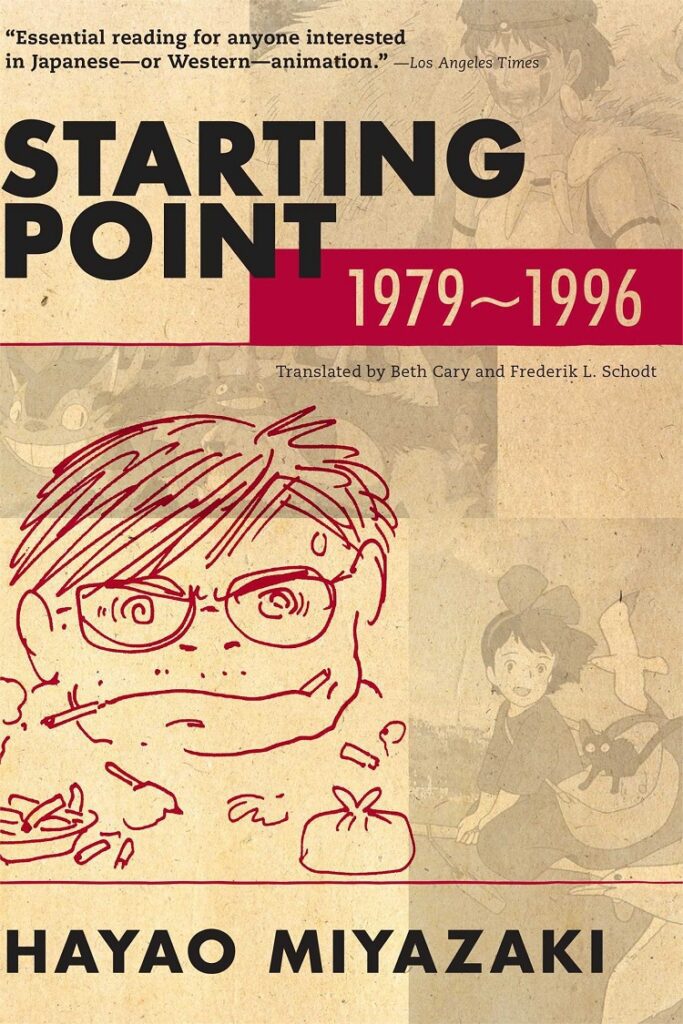

Starting Point and Turning Point, two volumes of “memoir” from Hayao Miyazaki, detail these contradictions. Neither are conventional memoirs, in that they are not after-the-fact recollections put down in prose, but collections of articles, memos, drawings, and plentiful interviews, which do not limit themselves to the world of animation, anime, or Ghibli studios (the studio that Miyazaki started with producer and fellow animator Isao Takahata just after the release of Nausicaa: The Valley of the Wind.)

Starting Point covers the years of 1979-1996. 1979 is a year before Castle of Cagliostro, his first feature film, was released, but Miyazaki had already been working in animation for over a decade. As befits a younger man’s energy, the writing collected here is diverse, including lectures given to younger animators, some pieces on Miyazaki’s own influences, and a number of reviews of other people’s animation (spoiler: nothing’s really good enough for Miyazaki, and while he doesn’t go out of his way to trash anybody else’s work – except maybe Osamu Tezuka, the godfather of manga, and a towering influence that Miyazaki had to slay to find his own voice – he is incisive in dissecting others work.) There’s no straightforward biography, but what Miyazaki reveals in a few sketches and asides in these writings paints a picture of a man standing somewhat aside from his culture who wants to simultaneously reject it and redeem it.

The constant theme of powered flight in his films (culminating in last year’s release of The Wind Rises) can possibly be traced back to his father’s aeronautical plant, which he ran during the war. Miyazaki’s constant ambivalence can be seen born in the same place, for as his father helped make the airplanes Miyazaki loves, he’s described as essentially a war profiteer whose lax standards meant a number of defective parts coming out of his factory and, presumably, planes that did not work, and ultimately dead pilots. This is about as far as these memoirs go in terms of personal revelation. There are no salacious personal details, very little mention of his wife or children (except that Miyazaki pointedly remarks he left the raising of his kids to his wife, and did not often see them when he was young). Miyazaki’s a self-described work-a-holic, and most everything interesting about him ends up in that work.

Miyazaki’s films largely refuses to paint any character as an out and out villain (Castle of Cagliostro and Castle in the Sky being notable exceptions, and his personal antipathy towards the military clouds his ability to make soldiers and generals into real human beings) but he doesn’t do so out of any naive sentimentality, and his opinionated, sometimes acidic writings demonstrate he has a bite. They also show he believes that his films carry a great responsibility to be something more than entertainment. For instance, in the memo where he describes the story of Kiki’s Delivery Service to his production team, he declares his “goal in completing this film is to send an expression of solidarity to young viewers who find themselves torn between dependence and independence.”

His other production memos contain similar sentiments, where it is clear that a thematic purpose exists for each of his films, and that these, indeed, come first. Ghibli films are a powerhouse now, but they were not always unquestionably a commercial force, and the pressure to balance creativity with commercial viability is present in all of Miyazaki’s contemporaneous writing. Nearly every film he makes is accompanied with a statement that this is probably the last film he’ll ever make, that he can’t do it anymore.

The theme of legacy, and having to do something important for his perenniel “last film ever” become more prominent around the time of Princess Mononoke, which is covered extensively in Turning Point. While Starting Point is thematically organized (sections are titled “On Creating Animation”, “People”, “My Favorite Things”, etc) Turning Point is split into a separate section for writings relevant to each film’s era: Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle, and Ponyo. This organizing principle is a little misleading, since while the writings occur around the time of each film’s release, they are not all directly related to it. The writing in the Howl’s Moving Castle section hardly touches on that film at all (which disappointed me, since I find it an underwhelming film and was hoping to see more insight into why Miyazaki decided to turn a fine novel with Diana Wynne Jones’ typical tight plotting into a mess. The best I could glean were a few oblique comments about disliking George Bush and wanting a movie that would be unsuccessful in America. Mission Accomplished, Hayao).

But some organizational issues aside, Turning Point is a fascinating volume in its own right. In these earlier years, Miyazaki is a man coalescing his influences and creating his way of working. Turning Point documents a veteran looking simultaneously back on his work and forward to his legacy, and while its scope is smaller than the previous volume, it goes into its individual subjects more deeply. The highlights include some transcribed talks with Miyazaki and a number of Japanese historians, discussing the era that Miyazaki recreates in Princess Mononoke. The film intentionally breaks with the typical societal representation of Japanese historical films – there are hardly any samurai, and very few peasants. Iron workers and a tribe of people left over from the Jomon era (Japanese prehistory) and other groups hardly ever seen in Japanese film make up the main cast. In his discussions with historians, Miyazaki is frank about what is researched and what is invented from whole cloth, and about how the issue of human encroachment on the environment is handled in the film.

It is easy to judge Miyazaki as a kind of environmental activist in his films, but his own words show he is not given to making easy judgments, and readily acknowledges the trade-offs between leaving the natural world alone and making it possible for humans to live. As Turning Point goes on Miyazaki’s pessimism apparently grows, and post-9/11 this manifests itself as a fairly facile condemnation of all conflict. He speaks out against nationalism and then in the same breath talks about how much better the Japanese mentality is on conflicts, and then in the next dismisses the Japanese as “foolish”. These are not the polished arguments of a master rhetoritician. They are the shifting thoughts of an artist still in conflict with his material, and trying to better express himself.

There are a number of documents in Turning Point about the special shorts that are made just for the Ghibli Museum in Japan (the design of which is also charmingly documented here). These little movies will never be shown outside the museum. Having this guaranteed venue allows more experimentation, in the sense that the director is explicitly looking to animate in ways he has not done before, without as much worry about the narrative, or commercial appeal. A short about a water spider is a chance to figure out a new way of making things look interesting underwater; another short about a girl finding a house is all about representing sound, including animating Japanese characters onscreen for sound effects.

The proposal for Ponyo, one of the last documents in the book (except for an afterword by Miyazaki where, with his typical good-natured pessimism, basically says he wishes these memoirs did not exist) includes not only a description of the story, but an explicit set of goals for the new visual style with simplified characters and a focus on motion. This volume predates The Wind Rises and Miyazaki’s apparently real retirement. Turning Point is a testament that, to the end of his career, Miyazaki has never rested. He has never stopped thinking about improving his art.

Both of these volumes (and I can’t see the point of having one without the other) are translated by Beth Cary and Frederik L. Schodt, veteran translators who have rendered Miyazaki’s words in clear, lucid prose. I’m in no position to compare the English to the original Japanese, but these books rarely evoke the sense of being on the end of a long line of people playing Telephone that can plague Japanese translated works. Both are part of Viz Media’s Ghibli Library series, and they belong on any animated film lover’s bookshelf.