Written by Tim Gebhart

Today’s digital media dislodged or diminished a variety of other media. Some are conspicuous: VHS and VCR. Others, such as the shriveling of newspaper movie ads, less so.

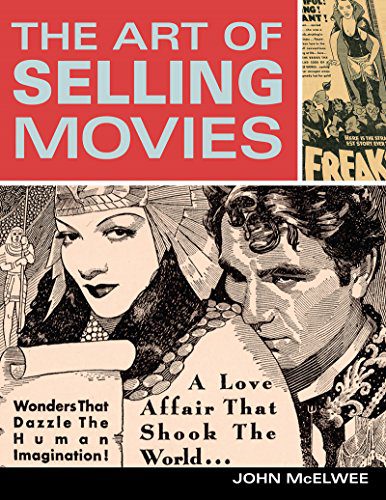

From its inception, newspaper advertising was a principal means of promoting movies. In addition to where and when a film was showing, these ads brought artwork, photos, and lively descriptions to the consumer. In The Art of Selling Movies, John McElwee looks at the history and evolution of this craft. As McElwee points out, his book isn’t about movies but the countless, nameless ad creators and their “skill, sometimes genius of pulling paid customers” through the doors of the theater.

The Art of Selling Movies surveys what McElwee calls the “Classic Era” of movie advertising, from silent films to the mid-1960s. It surveys not only stages in that history but various characteristics within each. McElwee also delves into the techniques, practices, and policies that steered this “disposable commodity” through the years. Perhaps most enjoyable for film buffs is that the coffee-table sized book is lavishly illustrated with actual newspaper ads. Each is accompanied by text describing its relation to the era and the particular topic.

McElwee first looks at the period from silent films to the 1930s. This was a time when ads were often created by local theater owners using “pressbooks” of art or tag lines provided by the studios. Theater chains, meanwhile, had mandatory ad guidelines. Regardless of who created an ad, McElwee observes, “No layout, however creative, was any good unless it sold the show.”

Selling the show in the silent film era shows that the puffery and superlatives often seen in movie promotion were there from the outset. Thus, a pen and ink illustration of dozens of people streaming into an Oakland movie house said of 1921’s Tol’able David: “Positively the greatest picture the T & D [Theatre] has ever shown.” Loew’s billed The Romance of Tarzan (1918) as “The Strangest, Mightiest, Most Extraordinary Love Epic Ever Conceived.” And playing off Theda Bara’s nickname “The Vamp,” an ad by New York City’s Lyric Theatre for Cleopatra (1917), centered on a photo of her atop and kissing a supine man with the text, “Forbidden But Now On View in the Stupendous Super-Vampire Photo Spectacle.”

Pen and ink art continued to dominate movie newspaper advertisements throughout the “talkie” era. It made sense because, at least as one movie house’s signboard said, movies with sound and speech were “the most amazing of all modern miracles.” So that, not artwork, became the emphasis . Ads were replete with phrases like “ALL TALKING.” When Douglas Fairbanks starred in 1929’s The Iron Mask, you could “HEAR Doug Talk.” McElwee notes, though, that movie goers may have been slightly disappointed. Fairbanks narrated a brief post-production prologue added to the film; the only sound during the film was an automated musical score with a few sound effects.

Regardless, the theme was consistent. Mary Pickford was “golden voiced” in Coquette (1929). Richard Dix had the “kind of voice you expected [him] to have” in Nothing But the Truth (1929). Cincinnati’s Palace Theater’s ad for General Crack (1930) proclaimed of star John Barrymore:

Yesterday a speechless shadow —

Today a vivid, living person

The Art of Selling Movies illustrates how the Depression also brought new approaches.

One reflected Hollywood before the enforcement of the Motion Picture Production Code in 1934. For example, rather than soldiers or battlefields, Kansas City’s Shubert Theatre’s first week ad for All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) featured a dressed-down flapper while the second week’s featured three scantily clad women. Meanwhile, a Paramount ad for Blonde Venus (1931), in which Marlene Dietrich plays a cabaret dancer who goes into prostitution, is built around a drawing of her in a scanty cabaret outfit. Even an ad for a musical comedy about a socialite falling in love with a riveter, The Hot Heiress (1931), featured a pen and ink drawing of the two kissing, with his hand on her breast.

The era saw tie-in promotions with products and often the product, not the movie, dominated the ads. These tie-ins could be as close as ads for Tom Sawyer (1930) also promoting Elder Manufacturing Co.’s “Tom Sawyer Wash Wear for Real Boys.” A more long lasting trend was to combine live entertainment with a movie. This trend would last a couple decades. Vaudeville acts were common early on, musicians were popular throughout and actors would make personal appearances (although, based on the book, rarely at their own movies). Whether live performers or the movie took top billing appeared to depend on the ability to draw people to the theater. It also would produce some odd combinations. In 1944, for example, Lionel Hampton, whose band featured singer Dinah Washington, would share the Cleveland Palace theater ad with Boris Karloff and Lon Chaney in House of Frankenstein.

And like the movies, the advertisements reflected America, includig attitudes toward race. A 1935 ad for a personal appearance by Stephen Fetchit told readers he would appear in a revue with a cast of “45 sepia stars” and a “bevy of gorgeous Creole beauties.” As an “Extra,” every performance would have “Colored Amateurs.” A 1939 ad for the opening of the Circle Theatre bragged of its air conditioning and advised patrons that its doors were open “to the white and colored public of New Orleans.”

World War II clearly impacted movie advertising. An ad for Scorched Earth (1942), a film about the Japanese invasion of China, promoted the film’s “HORROR, TERROR, BRUTALITY.” It promised the audience would see “Soldiers actually fall in battle! Writhing wounded .. mutilated civilians! Screaming mobs, huddled in horror! Starving children, rioting for food! Direct bomb hits on teeming cities! Actual fighting in Shanghai streets.” The following year an ad for March of Time: One Day of War about the war in Russia boasted that it contained “Front Line Action Films from the Cameras of Dead Men.” Yet there were also flashes of wit. One ad proclaimed The Hitler Gang (1943) as the “Greatest Gangster Picture” ever made, the story of “the gang that stole a nation.”

In post-war America, advertisements added a focus on bonus elements. The growth of drive-ins starting in the 1940s brought ads promoting the number of feature films to be shown, playgrounds for kids, and electric heaters for inside the car. As television competition grew in the 1950s, Hollywood decided that “TV couldn’t be beat for convenience, but it could be dwarfed for size,” McElwee observes. Ads promoted Cinerama (“puts you in the picture!”), 3-D, Cinemascope, and VistaVision. The industry also began using “saturation ads,” promoting films at multiple venues or over multiple territories. Given the number of movie houses in metropolitan areas, the public began seeing the smaller print, less showy ads that are common today. And by the 1960s, competition with television and between houses would lead to some odd promotions. For example, the Cinema Theatre in Greensboro, N.C., offered early bird matinees — at 6:45 a.m. — “for the ladies.” Given the early hour, attendees got free coffee and Krispy Kreme donuts. Later in its life, the theater would become a pizza-and-movie house.

McElwee’s selection of ads illustrates an overlooked aspect of American fiulm history. He also occasionally discusses how the textual and visual layout of an ad were aimed at specific objectives. Despite this, The Art of Selling Movies suffers from a pet peeve of mine. A lack of or failed editing and proofreading produces several virtually inexcusable flaws.

The text of the book consistently drops the articles “the” and “a.” As a result, some sentences feel more like abbreviated dictation. This is exacerbated by odd phrasings and sometimes convoluted sentence structure, some requiring rereading to comprehend them. One of the more discordant and consistently repeated errors is that McElwee uses the verb “accompany” as a noun. For example, in discussing silent movies he says “live accompany would easily fill the void” created by lack of sound. The correct word is the noun, “accompaniment.” Each of the many times this lapse occurs caused me to suspect the book’s attention to detail. This is reinforced by the occasional instances of obvious date discrepancies between an ad and the text.

As a visual tribute to the obscure creators of theater ads, The Art of Selling Movies works. Its textual analysis, however, is marred by errors that should have been detected and fixed long before the book was released.