Director/producer/actor Sydney Pollack (1934-2008) was one of the unsung heroes of cinematic and popular culture. His films ranged from Depression-era drama (1969’s They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?) to political thrillers (1975’s Three Days of the Condor, 1993’s The Firm, and 2005’s The Interpreter); from politically charged and doomed romance (1973’s The Way We Were) to soap operatic gender-benders (1982’s Tootsie), and so on.

Beside his filmmaking talent, he was a great character actor in film and TV, memorably playing Dustin Hoffman’s frustrated agent in Tootsie, a sympathetic cynic in Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999), Will’s loving but complicated father on the beloved sitcom Will & Grace (1998-2006, revival from 2017-2020), along many other excellent roles. Finally, he became a successful producer of many fantastic films such as The Fabulous Baker Boys, Sense and Sensibility, The Talented Mr. Ripley, Iris, and Michael Clayton. Because of this, he is forever known as being a famous Hollywood mainstay, even after his untimely death at age 73 from cancer.

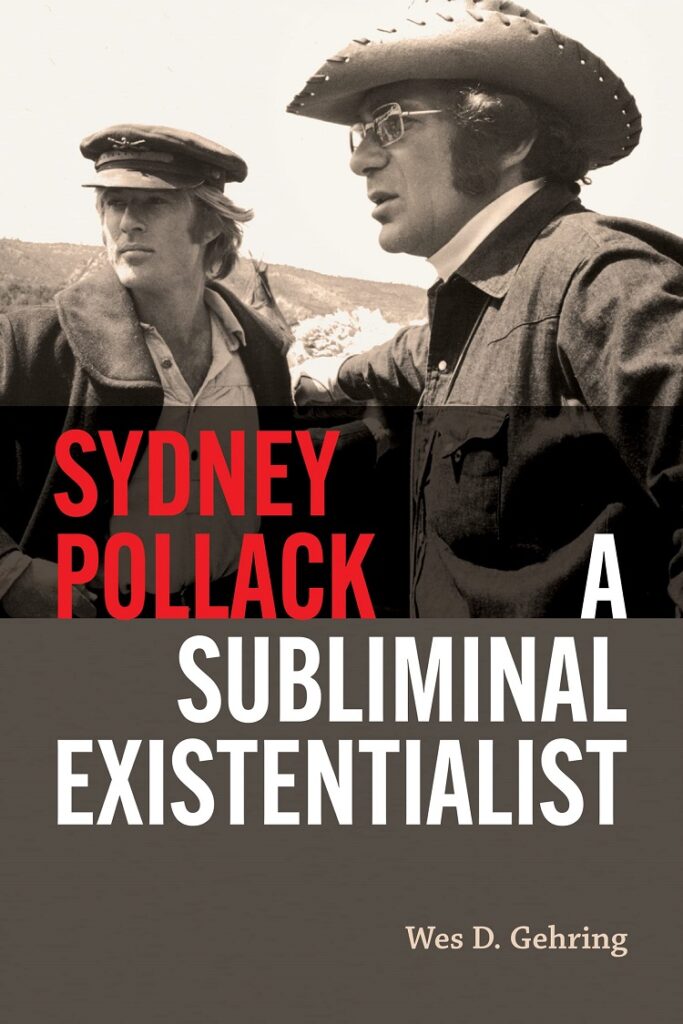

Despite all of the awards and accolades, he still happens to be very underrated, which is odd for a man of his remarkable stature. However, author Wes D. Gehring’s recent book, Sydney Pollack: A Subliminal Existentialist, provides a detailed and sharp renewal for Pollack’s obvious genius and work, by covering ten of his best films and his relationships with two legendary actors: teacher and mentor Burt Lancaster and Robert Redford, his frequent actor and muse.

Like most Hollywood biographies, the book starts with Pollack’s upbringing in South Bend, Indiana, with a not-so-encouraging father who didn’t care for his love for the theater, and a sickly alcoholic mother who died at just 41 years old. Of course, he had to escape. Where he landed is the place where he always wanted to go: New York (being a place where the Arts has reigned since forever). In this passage, there is emphasis on his high school teacher/theater director James L. Casaday, who became an important figure in his life and one who challenged him and other students with all forms of the Arts, from the opera to Cyrano.

The ten films that Gehring discusses are They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?; Jeremiah Johnson (1972); The Way We Were; Three Days of the Condor; Bobby Deerfield (1977); The Electric Horseman (1979); Absence of Malice (1981); Tootsie; Out of Africa (1985); and Havana (1990).

With Lancaster, Pollack got inspiration to become a director. He was impressed with Pollack’s calmness with handling difficult situations. With Redford, there was an instant rapport and chemistry. It’s no surprise to see this because Pollack directed him in seven films, including This Property is Condemned (1966).

There’s one particular passage about Tootsie that was very interesting because he was at odds with Dustin Hoffman on the set. However, Pollack had a method of dealing with him. He let him really get carried away with his impersonations of his character of Michael Dorsey/Dorothy Michaels. And that led to a compromise where Pollack saw that Hoffman was right about a certain scene. He figured that he used this method of agreeing with his actors, then everyone would be happy. Sometimes a director has to put aside his or her ego and work properly with their actors so that the film shoots will go smoothly and on time.

Sydney Pollack: A Subliminal Existentialist is an engrossing if slight exploration of a mammoth but still underappreciated filmmaker. When I write “slight,” it isn’t to be critical. I was just reminded that he did make other films besides the ten in the book. There could have been more details on those, such as Castle Keep (1969), The Yakuza (1974), and Random Hearts (1999). Otherwise, I was very much invested in it, and learned a lot about Pollack and his methods than I ever knew before. I think it’s a must read, especially for fellow film buffs.