Director Peter Bogdanovich is neither misunderstood nor unappreciated, I think. His claim to fame as a movie brat (though he might wince at that description) is secure. His early ‘70s trifecta—The Last Picture Show, What’s Up Doc?, and Paper Moon—cements the legend.

Those films endure.

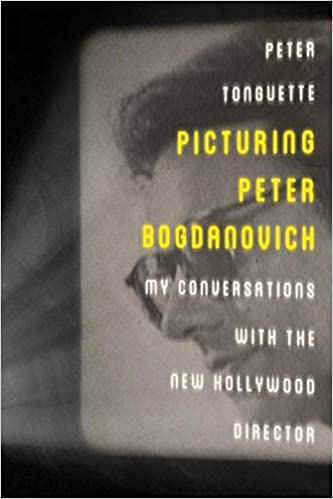

And they do so, because—as Picturing Peter Bogdanovich: My Conversations with the New Hollywood Director (Peter Tonguette; publisher: the University Press of Kentucky) makes clear—he had the talent and the ambition to direct films that could have sat alongside the classics of the old studio system of the ’30s and ’40s, but films imbued with a hipper, more adult-oriented sensibility. He’s a classicist, a snob with cred.

Long fascinated with the tragic arc of Bogdanovich’s career, I hoped Tonguette’s book would examine unflinchingly what went wrong, and when. I’m not sure it arrives at any breathtaking conclusions. In the last half of the book, though—an interview with the director, collated from multiple conversations—we get a fair glimpse into his story. It entertains enough that I raced through it in two days.

But Bogdanovich, rich subject that he is, is not a raconteur. Even if he fails to stoke his mythology or offer choice, eminently quotable remarks about his movies and methods, he is still honest. His view of his less well-received output is bracing. As a former film scholar and wunderkind who studied at the altar of directorial giants like John Ford, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, and Fritz Lang (to name but a few), his assessments of the films from his can’t-catch-a-break period are, for me, the juiciest parts of the book.

Some fascinating bits I learned from Tonguette’s book:

- Bogdanovich trained at the Actors Studio and played in summer stock well before he took jobs as a film essayist.

- On its path to becoming a cult classic, Targets, his directorial debut, required a significant amount of resourcefulness; and as a second trial-by-fire for this Roger Corman protégé, it proved that Bogdanovich had nothing handed to him; that he had the guts and stamina to problem-solve his way through a small budget and many limitations. In short, Picturing Peter Bogdanovich returns the man’s guerilla filmmaking roots to his stature. Connections and luck contributed to his rise to prominence; but, as the book illustrates, he had a lot more going for him.

- Cybill Shepherd, the director’s former beau and muse, has (in my view) an odd reputation as a dingbat. However distorted her public image may be, I don’t think she gets enough credit for the roles she played in a slew of ‘70s gems (e.g., The Last Picture Show, The Heartbreak Kid, Daisy Miller, and Taxi Driver). In the Tonguette book, Bogdanovich sets the record straight. She was an apt partner to him, an intellect who went on impulsive trips to movie revival houses, and read up a storm. She was more than just a pretty face.

- There are some awkward moments as the director speaks about his time as a “john” in Thailand, and the lengths he would go to help hookers secure a better life for themselves. I appreciate the candor here, but did not need him to remind me of the degree to which he used to be a generous donor.

Where the book frustrates is the author’s refusal to take a more critical stand on Bogdanovich’s perceived creative failures. I wanted the dialogue to be more of a tennis-match exchange, where the interviewer drops the fanboy adulation and allows his tastes and opinions to jockey with Bogdanovich’s (and to do so, of course, without sounding like a prick, as that would have been counterproductive to the director’s willingness to speak). I wanted it to be less softball and more of a gentle sparring. The first half of the book is an exhausting critical look at the filmography, Tonguette diving deep on each picture’s themes and techniques. It is impressive, but it’s a slog. He should have condensed it. Had Tonguette expanded on the interview format for publication, enjoining the director to talk more about the technical aspects of his craft, Picturing Peter Bogdanovich could have been a home run.

As it is, though, the book is splendid for what it offers: a cozy chat between artiste and sycophant. The best bits are the parts that add drama to the director’s ‘70s reign and his benighted ‘80s: the moments when he fights to make a name for himself under Corman’s mentoring; the moments when Bogdanovich realizes his ego and shortsightedness prevented otherwise intriguing films from having impact; and the occasion when he comes face to face with a brutal and sickening tragedy and must go on living and creating. These moments make the book, and his career, interesting. Bogdanovich was lucky, but he was also terribly unlucky.

And his career after Paper Moon is worth exploring. Many of those films are obscure. Today, though, the dedicated enthusiast can track them down without breaking a sweat.

Picturing Peter Bogdanovich: My Conversations with the New Hollywood Director comes out on July 21.