There are a handful of uniquely talented performers for whom, once or twice or maybe three times in a career, the stars align into a magical combination of the absolutely right role in the absolutely right play, film or TV show. Everyone will have their own favorites: mine include Carroll O’Connor as Archie Bunker; Zero Mostel in The Producers; Angela Lansbury’s Mrs. Lovett in Sweeney Todd; and maybe a dozen or so more.

Madeline Kahn had the fortunate misfortune to hit this kind of bulls-eye an amazing four times within a span of just three years in the early 1970s, creating characters that instantly rocketed past “memorable” to “iconically hilarious.” For then-hot director Peter Bogdanovich, she was first the shrieking frump Eunice Burns (“Howard! Howard Bannister!”), destined-to-be-dumped fiancée of absent-minded musicologist Ryan O’Neal in 1972’s What’s Up, Doc? Then, swinging a full 180 degrees on the sexiness scale, she was Depression-era tent-show floozy Trixie Delight in Paper Moon, trading Eunice’s bray for a baby-doll voice but still losing O’Neal, this time not to a madcap Barbra Streisand but to his determined scam artist partner, pint-sized Tatum O’Neal.

For maniac Mel Brooks, himself just coming into his own as a comedic force in films, she made her every moment on-screen sizzle with sexy mirth as Lili von Shtupp, the Marlene Dietrich-ish femme fatale of 1974’s Blazing Saddles (“It’s twue! It’s twue!”). Then there was that little-known comic gem Young Frankenstein, where a night of passionate sex with zipper-necked Peter Boyle gave her Elsa Lanchester’s lightning-streaked updo from Bride of Frankenstein, setto the unforgettable strains of “Ah, Sweet Mystery of Life!” (Her Trixie and Lili won Kahn back-to-back nominations for Best Supporting Actress.)

Following this amazing streak, there were other career highs (notably Wendy Wasserstein’s The Sisters Rosensweig on stage, which garnered Kahn a Best Actress Tony Award in 1993) before she was cruelly taken by ovarian cancer in 1999 at age 57. And of course there were the requisite lows that litter even the most successful showbiz career, including bad movies (e.g. At Long Last Love), mishandled or unlucky TV sitcoms (Oh Madeline, Mr. President and New York News), with a late-career berth in a plum supporting role on Cosby.

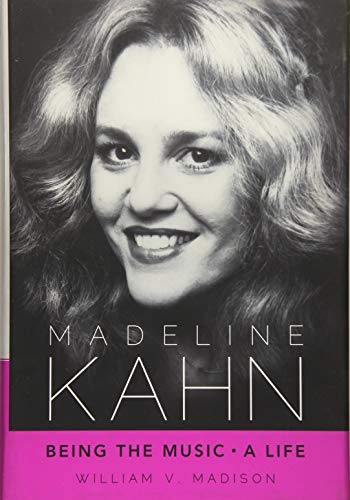

William V. Madison’s new bio of the musical and comedic chameleon, Madeline Kahn: Being the Music: A Life covers all this and more in exhaustive, sometimes exhausting, detail. Madison, a former CBS News producer, has certainly done his homework. There are well-chosen excerpts from Kahn’s own journal plus interviews with family members, friends (including frequent co-star Robert Klein), colleagues and directors, including Bogdanovich, Brooks, Lee Roy Reams (who directed her in a touring revival of Hello, Dolly!)and Eric Mendelsohn, director of her final film, the indie drama Judy Berlin.

Most of the career stuff is fascinating, particularly to a film and theater nerd like myself. Most interesting is a partisan but still fair-minded portrait of Kahn’s early exit from what should have been her big Broadway musical triumph, the 1978 On the Twentieth Century. The always insecure Kahn, faced with a vocally daunting lead role, a director (Hal Prince) not in tune with Kahn’s improvisational instincts and impatient with her lack of stage stamina, left the hit show after only a few months. Kahn’s loss was Judy Kaye’s gain: the understudy stepped in, but not soon enough to qualify for a Tony nod or to be preserved on the original Twentieth Century Broadway cast album. Kaye subsequently won Tony Awards for Phantom of the Opera and Nice Work if You Can Get It.

In Madison’s telling, the chronic insecurity that unfortunately blossomed during this episode stemmed from Kahn’s emotionally manipulative, financially irresponsible mother Paula, who more than once tried to leverage her daughter’s stardom into her own showbiz career. Fathers (biological and step) were distant, inconsistent or both, which gives context to Kahn’s skittishness about relationships with men. She had boyfriends but never shared living space with any of them until her last long-term relationship with John Hansbury, who she married soon before she died. There was also the relationship with a then in-the-closet gay actor, David Marshall Grant, which is practically an Actors Equity union membership requirement for a musical comedy diva.

For all the year-by-year, show-by-show detail and armchair psychologizing, however, I came away without a real sense of what Kahn was like as a person, as opposed to a performer. We read that she was uncomfortable with some of the coarser sexual humor of her most famous roles, and that her pursuit of performing perfection was the result of her need to keep directors/daddies interested and approving. However, these insights are more stated than illustrated, and they are often contradicted from one chapter to the next. Madison is so busy quoting from multiple sources that we don’t get enough of a big-picture take on Kahn, beyond his admiration for her talent and his sympathy for her woes.

To be fair, the author is working with two big handicaps. Kahn herself is no longer around to give her side of the story; even if she were, it’s not clear how much she would (or could) have shared. She was a reclusive, rather private person, not the brassy comedienne she sometimes played, nor a writer-performer (like her early colleague Lily Tomlin) who directly translates her own sensibility into her public persona.

This bio renewed my admiration for Kahn’s talent, persistence, and her ongoing desire to dig for the truth in even the most paper-thin and underwritten roles. That search for truth – the thinnest thread connecting even her most outrageous characters to some kind of human, heartfelt reality – is part of what made her a comedic virtuoso. Thanks Madeline, for bringing to life Eunice, Trixie, Lili, Elizabeth, and lots of other delicious damsels and dames.