Reading archives of old comic strips can be odd, because not only were these never meant to be perennial entertainment, but were the definition of ephemera, thrown out the next day with the rest of the old paper. That’s one of the refreshing things about them – they aren’t written with a modern audience in mind, and so remain suffused with the character of their times. It would be presumptuous to place weighty pretensions on any collection of old comic strips. Gasoline Alley, which started in 1918 as a gag strip about auto mechanics only inadvertently became a chronicle of American life through much of the 20th century because it had to come out every day, and it wasn’t a fantasy strip (except for the few times it was).

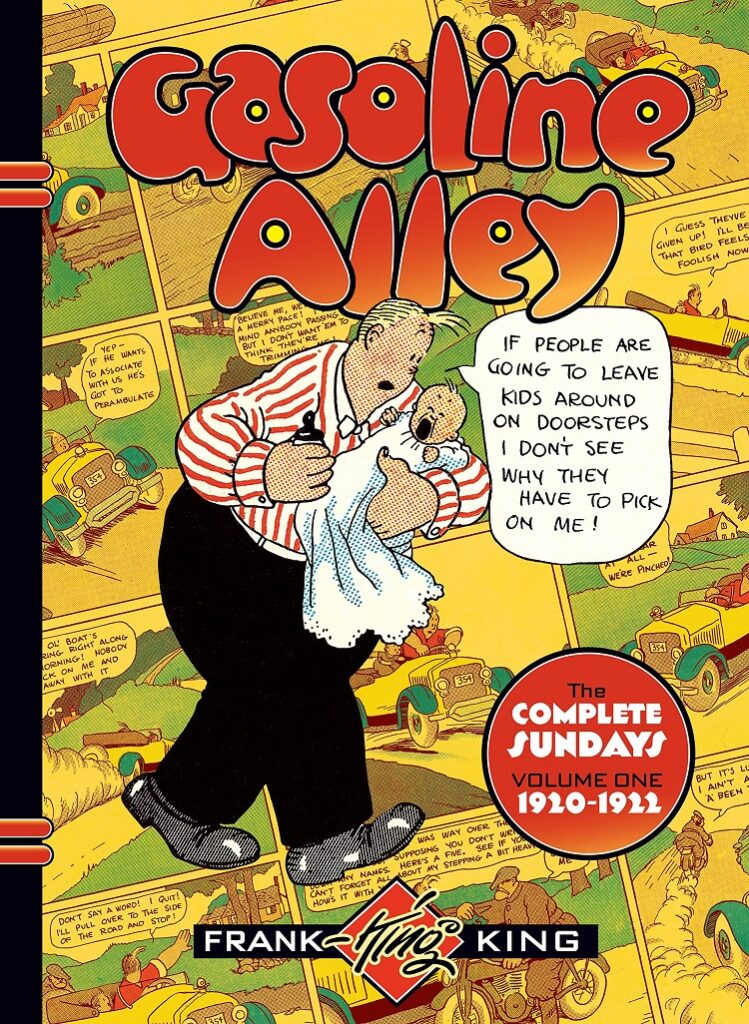

Gasoline Alley: The Complete Sundays, Volume One 1920-1922, is just what it says on the cover: a collection of the color Sundays. Gasoline Alley started on Sundays in a two-color strip on October 24, 1920. It differentiated from the daily strips by immediately pulling away from the car and driving jokes that made up the bulk of Gasoline Alley‘s content and focusing more on the domestic front. An explanatory historical essay (one of several fine text pieces at the front of this volume) places these strips in context: Frank King, Gasoline Alley‘s illustrator and writer, reasoned a strip with kid antics would be more popular than car jokes in the Sunday papers. So he wrote stories about the kids of his regular characters.

While the dailies rotated their focus on Gasoline Alley‘s large cast, the Sunday strips quickly become focused on Walt Wallet. His character design makes him look like he was intended to be the star from the beginning – all the other men around the Alley have cramped faces, with lines that point inwards, with wrinkles and creases and other details. Walt has a round, broad, open face, with less detail but more expression.

Which made him the perfect character to use when Frank King wanted to expand the cast with a new baby. Since Walt’s role on the strip was being a bachelor, King just left a kid on his doorstep. It’s from that moment, when Walt adopts little Skeezix (cowboy lingo, meaning “orphaned calf”) that Gasoline Alley shifts its focus on Sundays entirely to the adventures of Walt and his kid. The tenderness of their relationship, as Walt goes from schemes to giving the kid away into complete devotion is sweet without ever being tainted with gross sentimentality. Skeezix keeps Walt up at night, is a pain and a worry, but as he grows up, Walt grows with him.

And he does grow – Gasoline Alley made the rare choice in comic strips to advance the character’s age in real-time. Skeezix would grow older. In this collection, he’s eventually walking and saying his first baby words. This gave King the opportunity to really let the characters evolve, and while there isn’t a lot of strict continuity in these early years (at least not in the sense that a Soap Opera comic would be nearly incomprehensible to outsiders in the middle of an arc) the characters do have specific, continuing adventures of several weeks, sometimes just gags, sometimes adventures, especially later in the volume. The early Sunday Walt strips were based around attempts by his friends (and their wives) to overcome his perpetual bachelorhood. Walt would deftly avoid these social pitfalls, making his escape with some variation of the phrase “I know when I’m well off!”

Which to modern eyes barely looks like a punchline. Gasoline Alley is a comic strip; it is mostly made up of jokes, but humor from the past rarely translates directly. I was amused by some of this collection, laughed out loud a couple of times, but its value isn’t in it laughs: it’s in the twofold pleasures of getting a glimpse into the American past, and getting to experience the growing quality of Frank King’s art.

After more than half a year, the two-color palette was bumped up to a full four-color process, and King’s art increases in depth and complexity to match the new visual opportunities. Several of the Sunday strips involve complicated dreams and fantasy sequences, as when Walt gets visited by gnomes in the forest, drinks with them, then goes on a long mountain hike, using his own body as a bridge for the little people to walk across. It all occurs over the space of 12 panels, as do all of these Sunday strips. King didn’t play with the shape or format of his page the way George Herrimann would in his Krazy Kat Sunday Strips, and his landscapes tend toward naturalism, though King was perfectly capable of rendering a surrealistic art style if he wanted to (on June 4, 1922’s strip, the title graphic includes a highly stylized backdrop, with Walt saying “Gee, Skeezix! We’ve happened into some modern scenery!”)

There are some aspects of the comic that feel decidedly unmodern, in ways good and bad. The bad comes with the most obviously dated material, and that is in the character of Rachel, the nanny that Walt hires to take care of Skeezix. She’s black, and looks and talks like negative African-American stereotypes of the time. Rachel is not a stupid or demeaned character. She comes after a number of inadequate (and, to my sparse reading of the dailies, white and stuffy) nannies, and she’s the one who he keeps.

But the material doesn’t need warnings and apologias, because it’s hard to imagine just handing this book off to a modern kid and having them go at it (particularly given the very grown-up price tag.) And it’s primary pleasures are those most likely to be appreciated by an adult, art-loving audience: a window into an America of the past, a view of an evolving art style that meshes precisely with the limitations and opportunities of its medium. Gasoline Alley collections have a tendency to have trouble getting too far out of the gate, and no complete collection of any phase of strip is readily available. Gasoline Alley: The Complete Sundays, Volume One is a great start to a Gasoline Alley collection. Here’s hoping it moves forward without popping a tire, or running out of gas.