Disneyanity isn’t a theological work of compare and contrast or how Disney and world religions stack up against one another. It isn’t a bash on religion either. It also is not an in depth look at how Walt Disney himself truly felt about the topic; note, though, there is no church on Main Street, U.S.A. at Disneyland. What Douglas Brode does explore well is Disney’s outlook on feminism and equal rights while arguing that Disney movies can provide a sense of spirituality which for some “can no longer be found” in the traditional houses of worship.

Throughout the book, Brode cites the work of Joseph Campbell (The Hero with a Thousand Faces) and Sir James Frazer (The Golden Bough) to highlight connections between myth, magic, religion, spirituality, and Disney. The result of those connections is “Disney Magic,” that enchanting feeling many get walking through the turnstiles at Disneyland and as Brode states is close to “the same element that draws visitors to the Vatican.” Brode, however, does not suggest that either is an exact replacement for the other.

Brode does a fine job of analyzing Disney movies from Steamboat Willie (1928) to Soul (2020), as well as many forgotten gems such as Tonka (1959), Pedro (1942), and The Living Desert (1953). Noting and highlighting the spiritual messages that may be hidden there, which is entirely in the eye of the beholder, he even mentions how the more risque later works of Touchstone like Splash (1984) and Sister Act (1992) fit into the Disney catalog of films. His knowledge of these productions is interesting and informative. The author mixes fun facts with insight as to why Walt (and the Disney Company) chose to tell certain stories over others and examines how some were altered to fit the times and reach a wider audience in an ever-changing world. He points out that many stories and fairy tales had been altered from their original form to suit that place in time long before Disney released their version.

Brode’s perspective and thoughts on the Disney version/vision of these well-known archetypes is what I found most interesting about Disneyanity. He starts with the trope connecting mother nature (often presented as trees) to feminism and the goddess, which is seen many times throughout Disney films, animation and live action alike, as good, wise, and loving. This may explain the presence of the Wiccan good witch role seen from Trick or Treat (1952) to Mary Poppins (1964) and all the other numerous fairy godmothers that whirl around in Disney movies. There are, of course, bad witches as well, which provide the cinema world with some great villains. Strong females held key roles in many Walt Disney movies: Old Yeller (1957), Robin Hood (1952) and Davy Crockett (1954-55) are but a few. These strong women set the stage for the female heroes of the future in the films Mulan, Brave, and Frozen where the female lead could stand tall next to any male hero.

Disney’s take on the western TV genre of the 1950s is yet another fascinating part of the book. The Disney version is always based on true events even if the facts are cleaned up and altered a bit to better fit the Disney image. Davy Crockett started it all off and stands as the most well known of these adventure serials shown on the Disney hour each week. The Davy Crockett we all know so well comes from this representation: the hero from Kentucky who “knew every tree,” fought Indians and bears and died a valiant death in America’s version of the 300 at Thermopylae, the Alamo. Disney later aired The 9 Lives Of Elfego Baca (1958-59), a legendary (maybe because Disney made him so?) Hispanic lawman, lawyer, and politician. There is a scene there that shows Baca saying a prayer to the Virgin Mary, one of the very few times Disney would display religion on TV or film. Another Disney trailblazing show was Tales Of Texas John Slaughter (1958-61) where Tom Tryon, a known gay man (a topic Brode touches on slightly in other Disney works) plays the lead role. In a bold move for the time, Disney chose James Edwards to play Slaughter’s real life African American ranch foreman; there wouldn’t be another African American in a prominent role in a TV western for years to come.

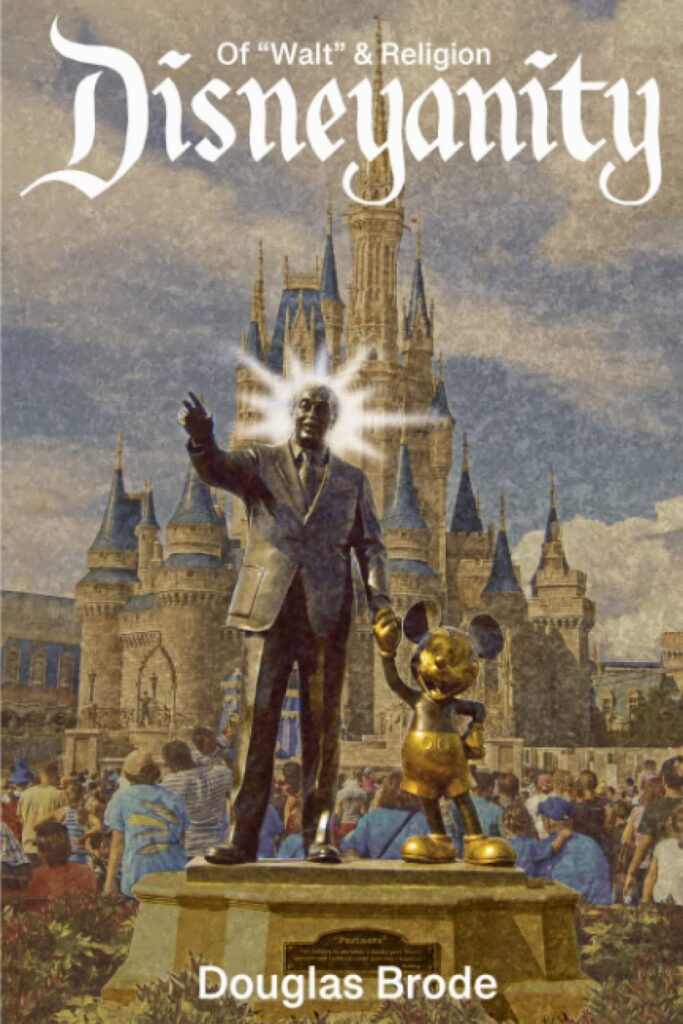

Disneyanity: Of “Walt” and Religion is an interesting and fascinating read that explores themes of spirituality that may be found throughout Disney films and television shows but that really all depends on how much one wants to read into things. Douglas Brode’s movie-by-movie breakdowns make it easy to revisit when needed, although it makes it a bit difficult to read straight through from cover to cover. While not a complete catalog of Disney movies, I appreciate Brode’s effort, knowledge, and perspectives which have given me a whole new outlook on the Disney film universe. Definitely a book that I’ll reference more than once while browsing Disney+.