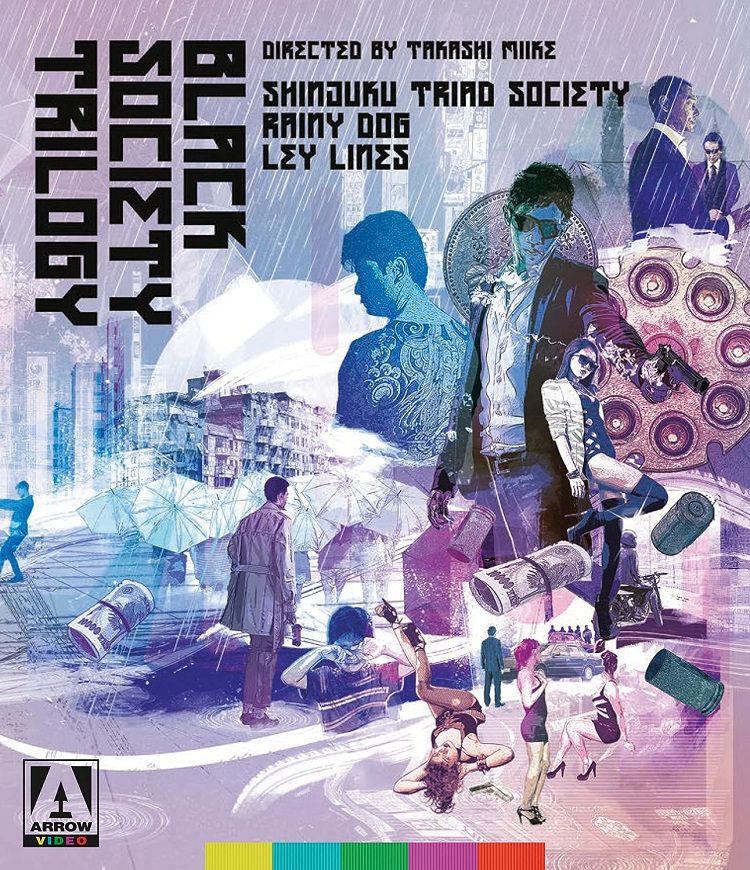

Takashi Miike is the Japanese director who will, seemingly, film anything. And anything does not just mean he’ll put the ugliest or craziest images on screen, but he will try literally anything. Hyperbolic nastiness, vicious violence, creepy sex including necrophilia? Yes. A madwoman chopping off a man’s foot with piano-wire to teach him a lesson? Sure. A children’s fantasy film with talking umbrellas? Why not? Or, in the so-called Black Society Trilogy, three (relatively) restrained movies about the difficulty of being an outsider, even in the outsider society of organized crime, where the need for family both sustains and destroys its outwardly tough, inwardly vulnerable protagonists?

These three films, Shinjuku Triad Society (1995), Rainy Dog and Ley Lines (both 1999) are only a trilogy in the loosest sense of the word – taking place mainly in the Shinjuku ward of Tokyo or in Taiwan, they share no running characters or plotlines, but are brought together thematically. They also showcase a remarkably restrained visual sensibility… for Miike. Which means they’re stranger and less tethered to reality than most filmmaking, but they do not go in for the full bore insanity that characterizes many of his other efforts. Instead, they focus on the characters and their shifting loyalties as they navigate the life of a racial outside in a relatively homogenous society.

Loyalties are intrinsically linked to heritage in Shinjuku Triad Society, where the bad cop shows his mob lawyer brother he loves him by beating him unconscious and stuffing him into the bullet train to go visit his parents. The broad strokes of the story involve the cop Tatsuhito trying to clean up the streets of Shinjuku. Not for the law abiding citizens, though: he’s a dirty cop who wants to push back the Chinese Triad gang who’re taking away turf from the local Yakuza who pay his salary. Complicating the matter is Tatsuhito’s heritage: he’s part Chinese, and is constantly reminded of the fact. Overlapping layers of identity are presented throughout the movie. Tatsuhito is a violent thug who wants to stop criminals. His main antagonist, Wang, is a deranged mob boss who may or may not also be Tatsuhito’s brother’s lover, and who is also of mixed heritage. He runs a vicious, ruthless gang, but funnels his money to a hospital in his native Taiwan (which also might be just a front for a child organ theft ring. It gets complicated.)

The outline is of a straightforward crime drama, but Miike is rarely straightforward. When a suspect won’t talk, Tatsuhito brings in a judo expert to throw the man around, and then sodomize him, which gets him to open up because he likes it. There’s a chase in the first third of the film where Tatsuhito runs after a car on the open road, and like T-2000 keeps up as it dashes down the streets. My favorite bizarre scene involves Wang and his Japanese associate informing a local madam that they’re giving her a smaller cut of the prostitution proceeds. Both Triad men simply repeat the same 3 lines, over and over again. And then Wang rips out one of the woman’s eyeballs. Shinjuku Triad Society is a perverse mix of humor and horror intertwined with a weirdly touching portrayal of men missing family connections.

Rainy Dog, maybe the most conventionally enjoyable of these three films, takes place and was shot entirely in Taiwan, with veteran Japanese movie tough-guy Show Aikawa playing a yakuza hitman, Yuuji, who’s waiting for the heat to die down before he can move back to Japan… until he gets two surprises, hot on each other’s heels. First, a phone call from his old confederates telling him that there’s been a restructuring in the organization, and there was no place for him anymore – he was excised from his old life. Then a woman bashes down his door to deliver a son he didn’t know he had. She’s taken care of the kid for a few years, now it was his turn.

For a Miike film Rainy Dog is straight-forward, even staid (again, for a Miike movie – there’s still a character who is introduced waking up on a building roof, then peeing off the edge and washing his face in his own urine). It rains constantly, and the drabness of the surroundings is matched by the dampness of Yuuji’s interactions with his son. The kid follows him around like the titular dog in the rain, and when Yuuji takes on a side job as a contract killer for a local syndicate, he thinks nothing of having his kid along when he shoots a man in the face (in front of the man’s own family, to boot.)

This scene demonstrates on of the key elements of a Miike movies, which is foregrounding the emotion and intent of a scene while divorcing it from strict reality. This mid-day murder, pointedly gunning down a man sitting across from his child, doesn’t end in Yuuji on a footchase away from the scene. No police pursuit, no hideouts. The intent is to show the brutality of the character’s world, how calloused he is from normal human interaction, and the tough row his son will have to hoe if he’s to get anything from this erstwhile and reluctant parent figure. It’s a plot point, not a major part of the movie. Hell, it’s probably only because Rainy Dog is a relatively slow-moving Miike movie that I even noticed the scene’s relative unreality, since there weren’t another dozen strange things occurring in the next scene to distract my brain.

Ley Lines, the final film in this set, returns to Japan and to the experience of rural Chinese-descended kids who try their luck in the Shinjuku ward. Straddling the line of Rainy Dog‘s less hyperbolic approach to story with the visual exuberance of Shinjuku Trade Society, Ley Lines is only really nominally a crime story. Yes, our three main heroes are kind of a gang, they sell drugs, make friends with a prostitute, and ultimately run afoul of the larger criminal organizations, but that’s a skeleton that the film’s true purpose, an examination of living a life looking from the outside in. Both Rainy Dog and Shinjuku Triad Society were about men in organizations. The only organizing principle for the three companions: Ryuichi, his brother Shunrei, and their goofy sidekick Chan, is that despite being born in and living their lives in Japan, they’re not considered Japanese.

They drift into some madman scheme to sell Toluene as a wonder drug, which gets them pulled in the orbit of a local crime boss. Still on the outside, the three want to look beyond Shinjuku to the greater world to seek their real fortune, maybe Brazil. But fake passports cost money, and the only people they know with money are gangsters, which leads to one of the patented Miike actions scenes: kinetic, wild, violent and bloody, and probably far more meticulously planned than they look (though on an interview on the disc, Miike does mention Tomorowo Taguchi, playing Chan, actually did fall through the plate glass window and got himself rather badly cut.)

It ends rather tragically, as do all of the movies in the Black Society Trilogy. Miike doesn’t make movies like this anymore, but neither does anybody else – in the multitude of extras available on the disc, context for the state of the Japanese film industry provided demonstrates how it was an accident of economics that directors like Miike, Kiyoshi Kurosawa and Hideo Nakata were able to distinguish themselves making these direct to video projects bursting with vitality and creativity. As long as there was a recognizable name starring and a reasonable facsimile of a genre, these movies made their money on pre-sales so the content was left largely to the directors. For large talents, this meant that before the VHS bubble burst they had a playground in which to do largely whatever they wanted. With Miike, this meant crafting wild entertainments that often had moments of subtlety and poignancy interspersed with the mayhem. These aren’t the movies on which his international reputation was built, but they do demonstrate what a cursory viewing of showier Miike movies can obscure: that his filmmaking has a very solid foundation of craft on which the madness is built.

On this Arrow Blu-ray release, the films come on two discs. There are newly recorded audio commentaries by Tom Mes, the author of Agitator: The Cinema of Takashi Miike, which provide insight and context on the films’ production, and the state of Japanese cinema when they were released. There’s also a pair of video interviews with Miike (clocking in at 48 minutes long) and with Rainy Dog star Show Aikawa.