In this time where people will often sit and binge-watch an entire television series, half of the population gleefully engages in such sittings regularly, while the other half will sit and wonder why the term “binge-watch” was added to the dictionary, especially since there was already a perfectly good word selected for marathon viewings in the first place: “marathon.” But no matter what side of the vernacular you’re on, there truly is nothing quite like being able to sit down and get a good proper feel for a particular performer or series. Thankfully, even film history’s lesser-remembered talents continue to get the right sort of treatment from the Warner Archive Collection through regularly released multi-film sets highlighting even the most faded of stars.

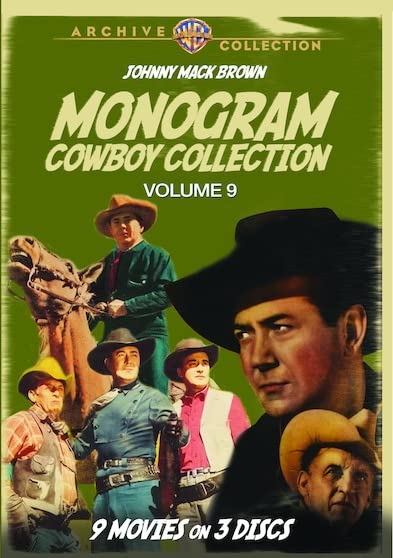

We begin this exercise with the latest entry to one of the WAC’s more regular offerings: the magnificent Monogram Cowboy Collection series. This is where we find a multi-disc set capturing various cowboy pictures manufactured and distributed for droves of matinee bijou dwelling youngling throughout the first half of the 20th Century (most of which would become hot commodities once television became a reality). Usually, the Warner Archive brings us a fun assortment of two or three forgotten legends from classic B-western (better-known as an “oater” to fans), but, as with a few instances in the past, the Monogram Cowboy Collection, Volume 9 is devoted entirely to the one and only Johnny Mack Brown.

And if there’s one cowboy picture star who deserves a solo set every now and again, it’s Johnny Mack Brown. The one-time college football hero shared the common dream of becoming a big Hollywood actor, and when Tinseltown beckoned, he followed. Alas, his career as an actor was more of the stuff reality was made of, but thanks to a little “rebranding,” Brown managed to craft a career out of very active B-western units at Poverty Row studios such as Monogram. By the time the nine quickies featured in the three-disc Monogram Cowboy Collection, Volume 9 set were released between 1946 and 1948, the portlier Brown started to look more like a 1930s Bela Lugosi pulling off a very good impersonation of Claude Akins in the 1970s.

Included in this set are The Gentleman from Texas (the only film from 1946), Trailing Danger, Flashing Guns, Land of the Lawless, Code of the Saddle, The Law Comes to Gunsight (all from 1947), The Fighting Ranger, Frontier Agent, and The Sheriff of Medicine Bow (all from 1948). Brown’s best sidekick, Raymond Hatton, appears in all nine films, eight of which were directed by Lambert Hillyer. Marshall Reed, Tristram Coffin, Bud Osborne, I. Stanford Jolley, Edmund Cobb, and Eddie Parker all pop up, along with regular Three Stooges foils Kenneth MacDonald and Christine McIntyre ‒ the latter of whom makes for a most effective villainess (something I think all Stooge fans already knew).

While the cinematic sidekick may have been commonplace in the storytelling process of the oater (if I may be so bold as to imply such films had a storytelling process), the second banana character was absolutely vital when it came to classic comedy duos. And somewhere down the rungs on the ladder of lesser-known comedic pairings, far to the north of RKO’s short-lived partnership of Wally Brown and Alan Carney, is another limited contractual partnership from the same studio: Bert Wheeler and Robert Woolsey. One wore big round glasses and was frequently seen in the company of a cigar. The other was an alluring, wild-eyed feller with the heart and mind of a child [insert Groucho Marx’s “…and I bet he was glad to get rid of it!” quip here].

Between their arsenal of impeccably timed double-entendres and the very fashionable looks the two sported, Wheeler and Woolsey essentially were what you might get if you were to pair the v1.0 prototype of George Burns along with a rather fey Dwight Frye. While Wheeler and Woolsey made more pictures together than the aforementioned Brown and Carney (one of which was actually remade by Brown and Carney!), the legacy of Wheeler and Woolsey hit a number of snags after they hit the bigtime with their first film in 1929. First, there was the time the studio decided to deliberately split the pair for solo features ‒ which failed. Then there was the introduction of the Production Code in 1933, which meant they had keep it clean.

Finally, in 1938, after appearing in 21 films together, Robert Woolsey passed away from kidney failure at the age of 50. Fortunately, the Warner Archive Collection has managed to preserve and release most of the team’s efforts to DVD-R. The latest (and perhaps last) addition to this roster is Wheeler & Woolsey: The RKO Comedy Classics Collection, Vol. 2 ‒ a three-disc, six-film set beginning with pre-Code musical comedies The Cuckoos and Dixiana, both of which were made in 1930, feature early Technicolor sequences, and are almost indistinguishable from many other musical comedies made around the same time (see: The Cocoanuts with The Marx Brothers), as they were all based off stage plays.

The next two films are the previously mentioned two solo features themselves. Everything’s Rosie (1931) with Robert Woolsey and Anita Louise is basically an uncredited adaptation of a 1923 W.C. Fields play, Poppy. Too Many Cooks (also from 1931) finds Bert Wheeler teamed up with the bubbly charms of the gorgeous Dorothy Lee, who appeared in many W&W films. Miss Lee also appears in the final two features in Wheeler & Woolsey: The RKO Comedy Classics Collection, Vol. 2 ‒ the medieval England romp Cockeyed Cavaliers from 1934 (also starring the lovely, doomed Thelma Todd) and the politically incorrect dentists in the Old West yarn Silly Billies from 1936.

Whereas the talents of Johnny Mack Brown and Wheeler & Woolsey spent the better part of their time on rural ranches or urban studios within the greater Los Angeles area for their moving picture projects, the one and only James A. FitzPatrick made a career out of traveling on the behalf of others. Over the course of five decades, FitzPatrick graduated from making independent shorts aimed at the very sort of matinee dwellers who idolized Johnny Mack Brown, to filmdom’s earliest travelogue featurettes. From 1930 to 1954, FitzPatrick hopped all over the world in order to bring American and British cinema patrons a chance to visit a far-off city or country (in Technicolor!) which were hard to visit due to timely events such as The Great Depression and World War II.

Here, in James A. FitzPatrick Traveltalks Shorts, Volume 3, we witness the final 64 shorts “The Voice of the Globe” produced, wrote, narrated, and directed, which initially saw theatrical releases from MGM. Spanning three discs, ten hours, and the course of 14 years (this third and final set from the Warner Archive Collection brings us the last travelogues FitzPatrick produced for MGM from 1940 to 1954), this collection of “one-reelers” (to those of you who still know what a reel of film was) is a great way to look at how the world once looked when humanity still possessed a bit of class, long before the Internet made it all too painfully possible for people to never want or need to leave the house for anything other than walking their dog.

Happy binge viewing, boys and girls.