Written by Kristen Lopez

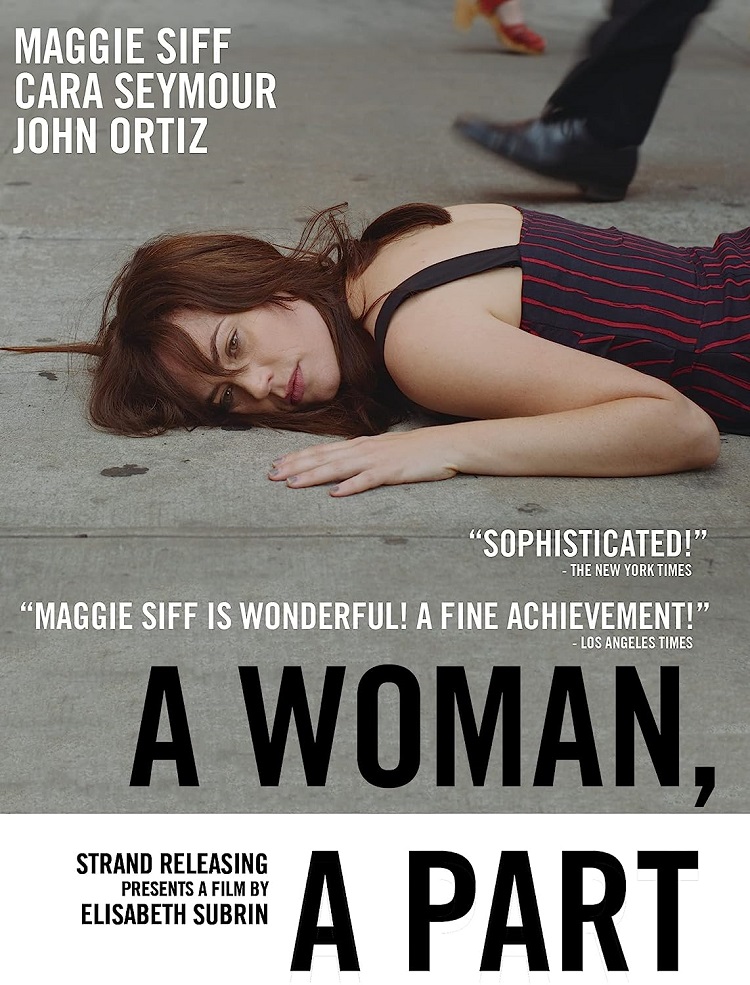

Whether it be directing or writing features, or just leading movies of substance, audiences are frustrated about how women are faring in the world of entertainment. Director Elisabeth Subrin’s debut, A Woman, A Part explores the different facets of the female personality with an aim towards demanding added nuance regarding women in cinema, creating a “women’s picture” without the pejoratives associated with the term. As the title implies, women are more than parts trotted out for a token bit of estrogen on a poster, and though Subrin’s assertions are life-changing, the presentation will please indie fans.

Anna (Maggie Siff) is a forty-something actress of a popular television series undergoing a crisis in every element of her life, whether it be personal, professional or existential. She decides to go back to New York, home to her theater roots, only to discover the friends she had before fame came calling are stuck with their own problems.

Subrin, who directs and wrote the script, compartmentalizes individual narratives for one grander whole, the “parts” her title implies. Anna’s Hollywood life is an endless series of brunches and meetings, with the occasional failed date in there for good measure. Waylaid with an auto-immune disease in the last year, Anna has lost her verve for acting despite it being the one thing she presumed would make her happy in life.

Maggie Siff, previously of Sons of Anarchy, sells the film’s woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown, an actress both apart from life and sick of playing a part in her career. Her face is a blank canvas, which, at times, leads to questioning her emotional intensity, but having watched Siff strictly as the waffling support system on SOA for several years gives her the chance to work with something different, and maybe toss out a sly critique of her own performance on the show she’s best known for.

Much is made of the ways women are shoehorned into stereotypical parts lacking any semblance of depth or individuality. A Woman, A Part works best when critiquing Hollywood as opposed to telling its own story. Anna is desperate to infuse her television character with something that makes her more than “a profession;” her reading from past scripts, where all the dialogue would definitely fail the Bechdel test resonates with anyone who’s asked why Hollywood can’t write decent women characters.

Anna’s return to New York introduces the film’s own tableau involving Anna’s friends. As much as this is Siff’s story, the basic tenets of her character see her doing little more than deconstructing and commenting on her friends’ issues, but the issues of others are more compelling. Cara Seymour and John Ortiz as Anna’s friends Kate and Isaac, respectively, yield subtler messages about femininity that are probably more relatable to the common audience. Seymour as the feisty, searching Kate takes the film by the reins and does fantastic work.

Staunchly dependable as the sole male character of any substance, Ortiz’s character bears something more interesting opposite Dagmara Dominczyk as his wife, Nadia. Nadia, as the housewife who gave up work, acts as a strong, if underutilized foil to Anna. Her declaration that she doesn’t want to be Isaac’s rock because “the rock is boring” beautifully sums up the film’s entire message – that females shouldn’t have to be supportive, but receive support of their own. Khandi Alexander also steals her few scenes as Anna’s agent.

Subrin’s screenwriting makes up for the typical indie foibles and techniques employed, with the handheld camera giving us a gritty propulsion. Some of the metaphors are a bit pointed, like Anna swimming in a sea of script pages, all boasting wasted women, but these issues will only stand out to those who consume independent cinema regularly.

A Woman, A Part opens the door of female representation in cinema, approaching the topic narratively and asking why women can’t be more than their femininity.