The Films

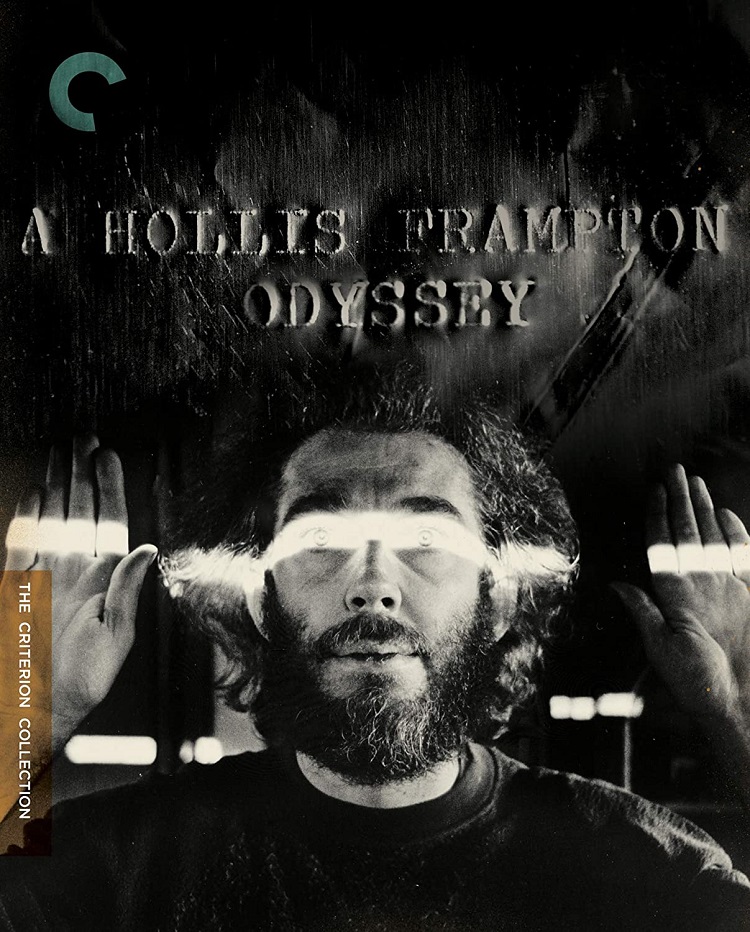

There isn’t much experimental film represented within the Criterion Collection library, but when the good folks there do decide to highlight an avant-garde filmmaker, they go for broke. Following up 2010’s sterling three-disc Blu-ray set featuring the films of Stan Brakhage, Criterion offers up A Hollis Frampton Odyssey, a varied collection of 24 films Frampton made from 1966 to 1979.

This is probably an even more audacious release than the Brakhage collection — Frampton’s films often aren’t as immediate or visually breathtaking as the hand-painted, hand-scratched kaleidoscopes of color seen in a number of Brakhage works. They can be incredibly oblique, filled with arcane references and esoteric wit. They can be painfully deliberate, holding a shot for what feels like an eternity. They can also be absolutely transfixing — a window into the mind of a brilliant artist — and the sheer unavailability of these major works elsewhere makes this disc one of the most important releases of the year.

Divided into four sections, the disc begins with a collection of six early films — some of Frampton’s earliest forays into the world of 16mm filmmaking after a career as a poet and still photographer. Some of these, like Process Red and Maxwell’s Demon, show the path of a filmmaker trying to find his way, shooting what interests him and juxtaposing it in unconventional ways with other images and stock material. But there are some highly idiosyncratic works here too, like the stop-motion Carrots & Peas, its bright, vivacious images of the titular vegetables accompanied by an alienating backwards-run soundtrack, and Lemon, a nearly static shot of the fruit with a slowly shifting light source revealing new dimensions to it.

Section two is devoted wholly to Zorns Lemma, an hour-long work that is astonishing for the amount of vast city imagery it incorporates and hypnotizing to experience. The bulk of the film consists of one-second shots of New York City signs, logos and billboards, with Frampton running through a 24-letter alphabet in order, over and over. As the film proceeds, he begins to substitute each letter with a shot of a normal activity — a child in a swing, an egg frying in a pan, a man’s hands peeling an orange — until all 24 letters have been replaced. The brief flashes of imagery create an enormous amount of dramatic tension — who would have thought an orange being peeled could seem so fraught with possibility? — and the myriad signs offer a fascinating tour of urban iconography all on their own.

Section three features selections from Frampton’s Hapax Legomena, an ambitious seven-film cycle that would’ve been nice to see here represented in its entirety. Nonetheless, we get three diverse portions of the cycle, each capable of standing alone. The most fascinating to me is (nostalgia), a collection of a dozen still photographs accompanied by narration by the legendary avant-garde filmmaker Michael Snow as Frampton and burned to a char on a hot plate in deliberate succession. The implications about memory, the physical nature of art, and the temporality of an image are given an additional beguiling twist by virtue of Snow’s wry narration, mismatched with the image that’s actually on the screen. Also included from Hapax Legomena are the clever but patience-trying Poetic Justice, a static shot of papers describing shots from an erotic screenplay piling up an a table, and Critical Mass, another fragmentation of sound and image that features Frampton working with actors for the first time.

The final section is but a small sampling of works from Frampton’s final unfinished project, which he died in the midst of. Planned to be comprised of more than 800 films running around 36 hours and shown over the course of one year, the Magellan cycle corresponded with three phases of what he called the Magellan Calendar. One can only get the barest sketch of what Frampton had in mind with this small handful of samples, but the creative ambition shown here is extraordinary.

The Blu-ray Disc

All 24 films included on the disc are presented in 1080p high definition and 1.33:1 aspect ratios. The condition the elements are in is almost uniformly excellent, with very little in the way of damage obstructing the images. Criterion’s presentation here gets you as close as possible to celluloid without the presence of the real thing. The rich, detailed images and clean, intact grain structures make you feel like you’re sitting in a darkened screening room, with only the whirr of the projector missing. The films all look fantastic — it’s unlikely you’ll encounter a repertory screening of these in the vast majority of cities, so having them presented like this here is a real treasure.

Audio is uncompressed monaural on the films that aren’t silent, and it’s generally just fine. Some hiss and crackle is there, but it’s a clean experience overall.

Special Features

Brief audio remarks by Frampton are available for a majority of the films and help offer some context alongside the more academic observations included in the excellent booklet. Excerpts from a 1978 interview with Frampton at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago are included, as is the audio of 1968 performance piece A Lecture, featuring narration from Snow. A series of images is matched to the audio in an attempt to replicate the experience. The disc also includes a selection of artwork from Frampton’s xerographic series By Any Other Name.

The aforementioned well-appointed 45-page booklet includes an essay by Ed Halter; film notes by Bruce Jenkins, Ken Eisenstein and Michael Zryd; and notes on film preservation and the difficulties of transferring Frampton’s work to a digital realm by Bill Brand.

The Bottom Line

A boldly uncommercial and an absolutely essential release from Criterion offers a thorough, fascinating introduction to a major player in the world of avant-garde filmmaking.