Director Tomu Uchida’s sprawling 1965 crime drama has finally arrived on home video for the first time outside of Japan. Based on a 1700-page novel, Uchida boils the story down to an still-epic three-hour film. Anchored by a riveting lead performance by Rentaro Mikuni, the film tracks the story of a killer and the cops pursuing him over the length of a decade.

The film opens in 1947 as a freak typhoon sinks a passenger ferry between Hokkaido and mainland Japan, resulting in hundreds of deaths. The chaos at the nearest port provides ample cover for three evil men to loot and burn a pawnshop and then escape in a small boat. When the local small-town detective begins searching for them on a neighboring island, he discovers their burned boat and two corpses, leaving one crook in the wind with no clues to his whereabouts.

Meanwhile, a loopy young prostitute named Yae encounters a starving man named Takichi on a train and provides him with the small kindness of rice balls to eat, leading him to follow her home, seduce her, and eventually give her a small fortune when he quickly makes himself scarce. This cash windfall allows Yae to retire her debts and the debts of her relatives, and also gives her a nest egg to move to the big city of Tokyo to make more money in her chosen profession. This is where the film gets a bit confusing in focus and chronology, as we follow Yae exclusively for a major block of time as she moves to Tokyo, finds a new employer, and at some point jumps forward ten years with no announcement.

Once we figure out the time jump, Yae spots a picture of Takichi in a newspaper article describing him as wealthy charity supporter, leading her to track him down to thank him in person for the life-changing cash he gave her in the past. Unfortunately, he’s living under an assumed name and has no interest in anyone knowing about his past, especially since he’s the murderer responsible for killing the two other robbers at the start of the film. Their showdown sets up the involvement of the Tokyo police, as well as the original small-town detective who first tried to nab Takichi, throwing away his career during his dogged pursuit.

The film works best when Mikuni gets to explore his duplicitous character, showing his character’s internal conflict as he tries to reconcile the wealthy pillar of society he has become with his past life as a scruffy killer. It’s also entertaining to watch the cops trying to put all the pieces together, especially when the old original detective realizes he might finally be able to wrap up his case. Not as effective is the time spent on Yae, an oddball who is portrayed as a mental halfwit. Certainly her character is crucial to the overall plot, but Uchida devotes far too much time to showing her career progression and family life, nonessential elements that do little but extend the runtime.

Uchida has a very active camera here, unfortunately a bit too active in the pre-Steadicam era. His attempts at immediacy with handheld tracking shots result in some unpleasant shakiness at times, although the kinetic camera work is a benefit overall. He also employs an odd recurring effect of turning the image negative at certain times, apparently to signify Takichi’s turns to the dark side. Overall, pacing is strong considering the length of the film, making it feel much closer to two hours than three.

The new high-definition transfer was produced and supplied by original studio Toei from the best available archival materials, with additional grading and picture restoration by Arrow Films. The film appears to have been expertly archived and/or restored, with a gorgeous high-contrast black and white picture showing no noticeable defects. Images are crystal clear in sharp detail even in the darkest night scenes, while film grain is surprisingly low. It’s a spectacular, top-notch transfer that assures viewers an experience surely even more optimized than its original theatrical release. Sound is presented in its original mono format and exhibits very little hiss.

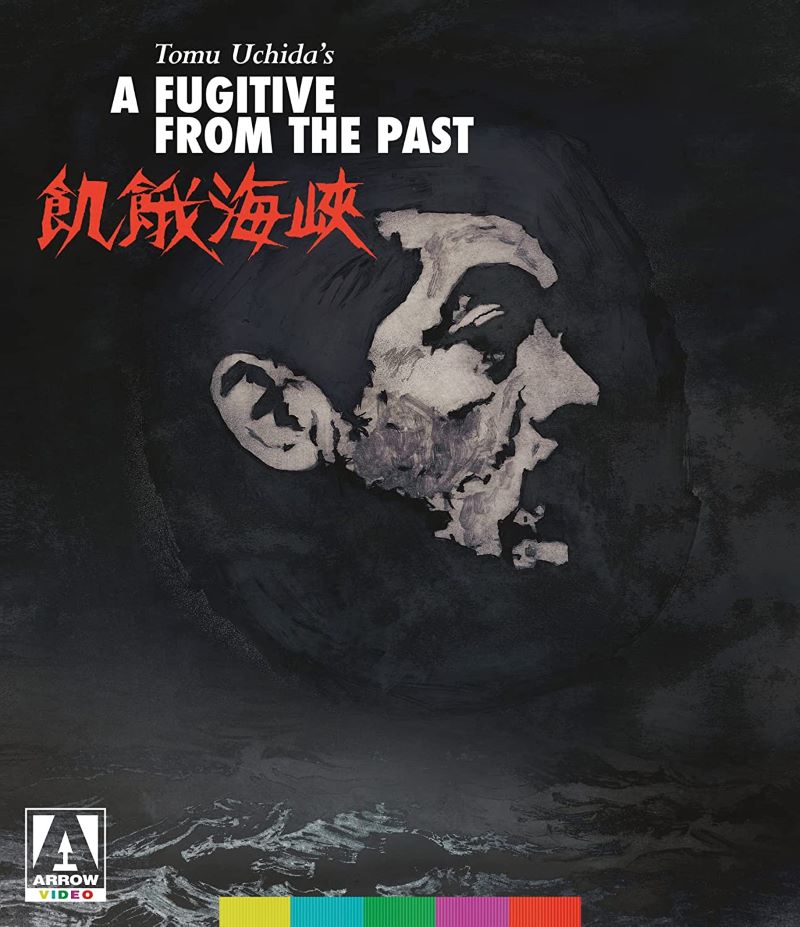

The bonus features include a lengthy “introduction” by a writer/curator who veers off into Uchida’s career and the rest of the Japanese film industry in his zeal to show off his film knowledge. Multiple scene-specific commentaries from other leading Japanese film scholars are also included, but they don’t work like one would assume. Although they seem to indicate that one scene would be shown and discussed, instead they function more like standard making-of bonus features, calling in other stills and footage to support the topic under discussion. The disc also includes the original theatrical trailer, an image gallery, and Uchida’s filmography. The enclosed booklet also contains a lengthy essay providing more background on Uchida and the film, while the case sleeve is reversible, featuring original and newly commissioned artwork.