“Prophecy is dirty and ragged”, says Vaughan, while complaining about the cleanliness of the tattoo he gets on his chest. It’s of a steering wheel, part of his attempt connect himself, as much as possible, to the object of his sexual gratification, and obsession. He loves cars, but not when they drive. He loves them when they, as the film’s title says so simply, Crash.

Where Vaughan and his obsessions come from is obscure, but he becomes the central figure in the life James Ballard (James Spader) after he survives a car crash. The driver of the other car does not – he’s thrown through the windshield, and lands in Ballard’s front seat. When Ballard looks across the way, into the other car, he sees the dead man’s wife, Helen, who immediately bares one breast. The next time they meet is in the hospital, as Ballard’s leg is healing but is still pinned to a brace. The time after that is at the car impound lot; moments later, they’re having sex in the front seat of Ballard’s new car – incidentally, the exact same model, down to the color, that he was driving when he crashed into Helen and killed her husband.

Apparently, the immediate rush of the impact of a car accident has, for these jaded individuals, overtaken the other more quotidian aspects of danger that random illicit sex entails. That used to be Ballard’s turn on, since he and his wife would regularly couple with strangers, and then come back home and bang each other while they discussed the details. This seems to be more the wife Catherine’s turn-on than his, and every time they come together there’s no eye contact. Just chatting and thrusting. But this new experience with Helen and the car accident has Ballard in its clutches. With her, he attends a show put on by Vaughan. It’s a recreation of James Dean’s fatal car accident, at full speed. Vaughan narrates it from the passenger seat.

It’s a bizarre scene in a film filled with bizarre scenes, from David Cronenberg whose entire oeuvre has been delving into the bizarre, the deviant, the psychosexual, and the just plain weird. Though he’d come on the scene in the ’70s making movies that straddled science fiction with some of the most outlandish body horror seen on the screen to date, Crash signaled a change in his focus, and a move in his career away from the horror genre (with the exception of his next film, Existenz.)

Crash was still outlandish, and horrifying – hell, it won a special jury prize from Cannes for Audacity. But it takes away the more easily grasped generic aspects of his previous films and confronts the viewer with a stark, odd vision that has no exploding heads or mutating men, just sexuality strained by the pressures of the late 20th century. In essence, the film’s car accidents are more meaningful than the direct sexual encounters, since at least the crashes make some sort of permanent difference. They leaves marks much less ephemeral than the swapping of body fluids.

I’ve made little attempt to describe the plot of the film because there’s little to describe. After the car accident and the connection with Vaughan, Ballard falls in with his coterie of accident victims, all of whom have bought into his strange new fetish. They sit at his friend’s house watching tapes of car crashes, occasionally sexually gratifying each other as they do. Vaughan himself has no home, other than his car. There’s some small momentum in the story as Ballard finally wraps Catherine into the world, which might be enough to punch through her cold, superior facade which may be too much for her to bear.

But the film is largely a series of sexual encounters, punctuated with near misses in cars, or actual accidents. It has an almost mesmeric rhythm as it moves from foreplay (watching a crash video, sitting in a car at a showroom and tearing part of the seat, etc.) into the action. And the action is very mechanical. The tight maneuvers of actually getting two adult bodies into position in a small car to engage in the sexual necessities is all part of the action. The discomfort and inconvenience is all, as they say, part of the kink. And deliberately uninteresting for anyone who doesn’t share the kink (which is to say just about the entire human race.)

What is remarkable, watching the film for the first time in nearly 25 years since it was released to massive controversy, is how remarkable it isn’t. Society has caught up (or degenerated) to the level of Crash‘s ragged and dirty prophecy. Dehumanized and mechanical sex is central to the film’s theme, but so is the addictive quality both of perversity, and the encouragement of it by peers. Vaughan alone is just a crazy guy. Vaughan with his accident victims all egging each other on into the next level of danger, the further degree of commitment to an insane, dangerous, and perverse ideal becomes the leader of a movement. It’s not an uncommon sight in the world of social media, where any bizarre idea, however self-destructive, stupid or perverse, has a constituency.

That is my interpretation and response to the world Crash presents, but Cronenberg never stoops to moralizing. He presents his characters and their abnormal actions almost clinically. Crash, all about sex and obsession, is, with the exception of the character of Vaughan, deliberately devoid of passion. The near constant sex is mechanical, awkward, and perfunctory, except when it’s violent. It’s a fascinating movie, but not engaging. Not involving. Definitely not fun. It’s an important film in Cronenberg’s canon, the foregrounding of the sexual interests in his work unleavened by science fiction aspects. It was interesting to revisit it, though there’s a reason I’ve seen Shivers or Videodrome or even Existenz several times, and this is the first time I’ve revisited Crash since its theatrical debut in 1996. It’s fascinating, but grim, cold, and relentless.

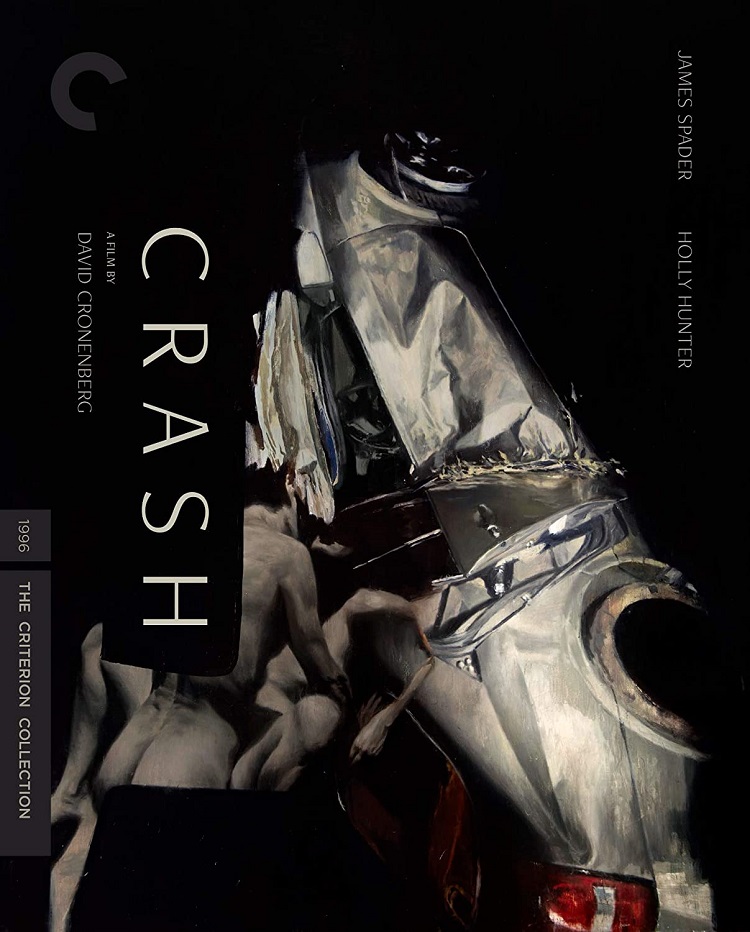

Crash has been released on Blu-ray and on DVD by the Criterion Collection. Extras on disc include a full-length commentary by David Cronenberg (from 1997). There are also several video extras: a press conference from Cannes (38 min), a lecture by Cronenberg and Ballard from the British Film Institute (102 min), and press kits footage (9 min) There’s also trailers, and an essay in the included pamphlet by Jessica Kiang.