Julie (Dominique Labourier), a young woman with big, curly red hair, sits on a park bench distractedly reading a book on magic. Her feet create runes in the dirt while she observes kids playing, a bird chirping, and a cat prancing. Another young woman, Céline (Juliet Berto), extravagantly dressed, passes by. When she drops her sunglasses, Julie jumps to the rescue. She squeals and “yoo-hoos” at Céline to no avail. Céline drops a feather boa and other items. They chase each other through the streets of Paris’s Montmartre district like Alice following the White Rabbit.

Eventually, Céline checks into a motel and doesn’t come out, leaving Julie to wander off on her own. The next morning Julie stalks about the area and finds Céline in a restaurant. She returns the dropped items as if they were nothing and leaves. Later, Céline shows up at the library where Julie works but doesn’t say a word. She only sits in the kid’s section making lots of noise. She traces her hand in one of the books while Julie puts her fingers into a stamp and leaves prints all over some papers. The two never discuss the games they are playing together. Their bond is an emotional one, connected through playfulness.

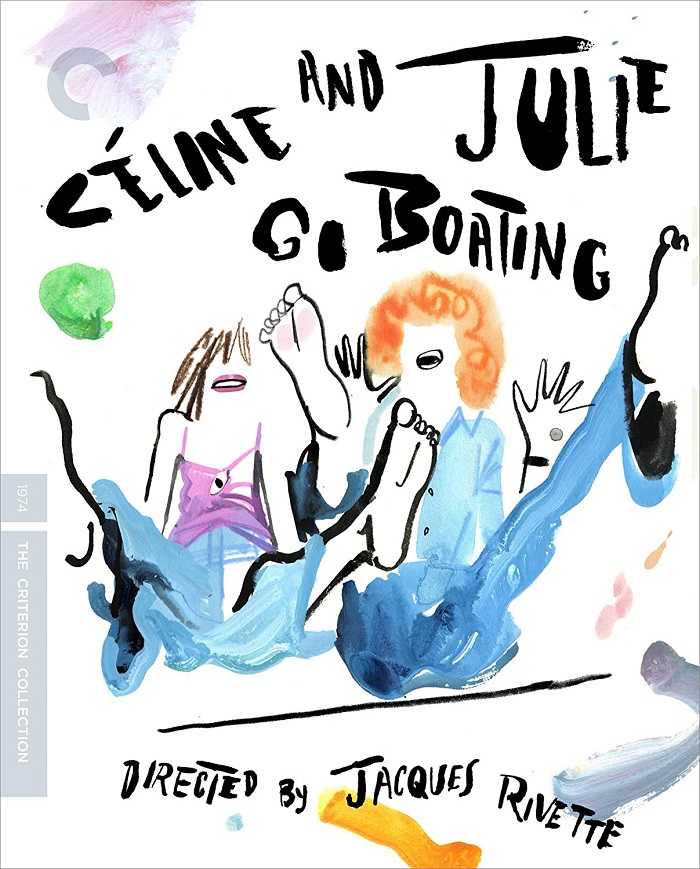

Céline and Julie Go Boating was the fifth film by French director Jacques Rivette. Like a lot of his films, or at least the few I’ve seen, it is a strange, bewildering, long film that invites a variety of interpretations. Unlike many of his other films or at least the few I’ve seen, it did not rely heavily on improvisation but was carefully scripted. It was very much a collaboration with his actors. They would get together each day, having most of the story already plotted out, and put together the scenes they were to create that day. Then within the confines of those pages, they would fill the screen with lively performances. Labourier and Berto were friends in real life and it shows in their performances. Much of the film feels like the two just hanging out.

After that auspicious beginning, the film continues into spectacular strangeness. Julie quits her job and the two move in together. They tell each other elaborate stories making it impossible to tell where truth ends and the stories begin. Céline tells her friends that Julie is a famous American heiress who lives in a mansion with a heart-shaped pool and is going to make her a star. Julie shows up to an audition meant for Céline (she is a magician) and completely botches it. She sings a strange song then berates the audience for being there.

Julie walks to an address Céline gave her in one of her stories. She knocks on the door and it opens. Later, she is pushed out of the house and stumbles to a taxi. Her head aches like she’s been drugged and she can’t remember what happened on the inside. There is a piece of candy in her mouth and she doesn’t know how it got there. At times, she gets flashbacks of what happened, just snippets at first. The next morning Céline shows up at the house and the same thing happens to her. Julie meets her when she stumbles outside and the two discuss what might be going on. Céline also had a piece of candy in her mouth and later she discovers that if she puts it back in her mouth she gets longer flashes, like disjointed scenes in a movie, about what happened.

These flashbacks appear like an old Hollywood melodrama. There is a love triangle between a widower and two women. Tragedy strikes when a child dies. Céline goes back the next day. The two of them suck on the candy to learn more. Both of them see themselves appearing in this story as the child’s nanny.

Writing all of that down, I realize none of that makes any sense on paper. In truth, not much of it makes much sense on the screen. Rivette doesn’t feel the need to explain anything to the audience. It has the logic of a dream. Images appear on the screen and disappear just as quickly. The ladies at the center of the film exist and they don’t exist. They tell stories that may or may not be the truth. The mystery of the house unfolds and is not understood. We see those scenes play out over and over, sometimes from different angles, often in differing lengths.

It is a film that invites differing interpretations. It is about art, and stories, and cinema. It is about how we watch films and interpret them. It is about how our memories of films change over time and how we interact with them. It is boldly feminist. It is about how these two women pull each other out of their dull stories and create new interesting ones. It is about their laughter. It is a lesbian romance or a profound friendship. It is fascinating and absorbing, overlong and dull. It is all of these things and none of them. It is a film I highly recommend, while also recognizing some people will absolutely hate it. It is a film I look forward to watching again. I wonder how my interpretation will change.

Criterion has outdone themselves with this release. It features a new 2K digital restoration and uncompressed monaural audio. Extras include an audio commentary from critic Adrian Martin, a two-part documentary by Claire Denis about Jaques Rivette, new interviews with the filmmakers, and other archival interviews about the film. It comes with the usual booklet featuring an essay on the film and a 1974 piece by Berto.