H.G. Wells has had a number of books turned into classic films, including The Island of Lost Souls (1932), and The Time Machine (1960). His direct experience with the cinema was less than satisfactory however. Wells’ only full-length feature film was Things To Come (1936), which has just been released on DVD as part of the Criterion Collection. It is one of the strangest films I have ever seen, for a number of reasons. No matter what you may think of it in the end though, it is a truly unforgettable piece of cinematic history.

The two-bit synopsis of the film is that Wells looked into his crystal ball and predicted the next 100 years. It actually begins in 1940, on Christmas Eve, with war being declared throughout Europe. The location is Everytown, which is a stand-in for London. The war drags on for so many years that eventually everyone forgets why they are fighting. We enter a new Dark Ages, and in 1966 a disease called the Wandering Sickness decimates the population the way the Black Death once did. Those who are infected become the new enemy, and when The Boss (Ralph Richardson) decrees that they be shot on sight, he wins the favor of the people.

The Boss is a petty dictator, but his era will not last long. During the war, just about all of the existing technology had been destroyed. One day, a futuristic plane flies into Everytown, piloted by John Cabal (Raymond Massey). He is part of an organization that calls itself “Wings of the World,” comprised of the technological elite. Cabal is arrested, but his fellows release him, and basically take over. The years 1970-2036 are a time of massive building, very much a technological revolution, as opposed to an industrial revolution. At the very end, as a giant space-gun is being prepared to shoot people to the moon, some neo-Luddites voice concerns about too much progress. This is met with a speech about balancing the two sides for humanity’s future as the colossal Wagnerian musical score reaches its climax and the film ends.

That ending may sound balanced, but the orgasm of building, of how technology will lead the way to a glorious future has to be seen to be believed. We must remember that this movie was made in 1936, when the idea of replacing old dirt roads with modern paved roads was just one very obvious example of how important progress was at the time. I guess the real surprise is that Wells put any thought of restraint in the movie at all. The whole point of Things To Come is that technology will lead to paradise. The trouble is that the world of 2036 as presented here scared the crap out of me. One can only imagine what audiences thought about it at the time, some 77 years ago.

The biggest problem I had with the film was the dialogue. There is just too much, way too much. Wells was a writer, who was trying to make a film about philosophy. You can write out those thoughts in a book, but having your character verbalize them in long speeches is the kiss of death for a movie. I was very much reminded of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead (1949) in this regard.

As for the look, the temptation is to refer to Fritz Lang’s classic Metropolis (1927), but Things To Come was actually intended to be the anti-Metropolis by Wells. The author wanted to present a positive vision of a technological future, which is quite the opposite of Lang’s film. Still, there were not a lot of options in visualizing futuristic high-tech on film at the time, and there are some superficial similarities. What I came away with was the neo-socialism of the old WPA films and newsreels of the time, in terms of look and design. The robotic marching of German soldiers in Triumph of the Will (1935) is also very strongly referenced.

As for the philosophy, “neo” is the operative prefix, and Wells has it both ways. His dream society is both neo-fascist and neo-socialist. The elite of scientists, doctors, and engineers rule the land. It may be intended as a benevolent form of rule, but it is clear that their power is absolute. If people like The Boss have to be crushed for the future of mankind, then so be it. We are all supposed to work together in harmony, and the government will take care of us. It is pretty obvious that capitalism has been left behind. In the end. I was just flabbergasted to realize that Wells’ vision of Utopia was a world of happy human robots.

That Things To Come is meant allegorically is confirmed in the final scene, with the space gun. In 1936, it was already a well-known fact that voyages to outer space would be in some form of rocket, not by being shot out of a huge gun. Wells knew this, but could not resist the symbolism of turning those deadly guns that had killed so many into a force for good, so he went with the space-gun idea.

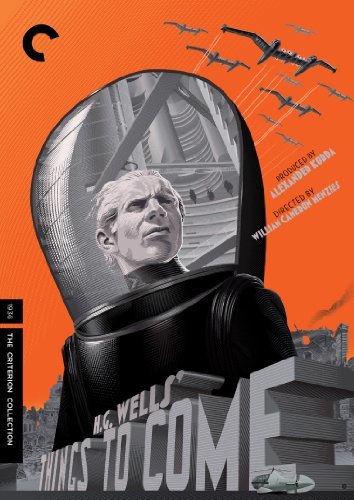

I didn’t coin the description “an illustrated lecture” about Things To Come, but I agree with it. H.G. Wells was a living legend at the time, and was given far too much control over this film. It is hard to believe that producer Alexander Korda would permit this, but he did. Where this movie will probably never lose its fascination for people is in the look, as it is quite impressive. You can see how important this was right from the top, with the hiring of William Cameron Menzies as the director. Menzies was a designer, not a director, and was far more interested in the visuals than in the acting.

In the bonus feature “Christopher Frayling on the Design” (27 min), the cultural historian discusses a number of the design elements of the film. He also mentions that Wells and Korda had first met in 1934 to discuss the project, then titled “Whither Mankind?” Their negotiations went on for quite a while, with Wells winning a great deal of concessions that Korda would not have normally given over.

The music is another very important aspect. In fact, it is really too much at times. Apparently this is an area where Korda actually reined Wells in somewhat though. Wells’ original idea was for the dialogue to be written to the music, like lyrics in an opera. In “Bruce Eder on the Score” (16 min), Eder explains how Korda flatly refused to allow the music to be written first, and the movie then made to fit the score.

There are a couple more intriguing short bits. The Bauhaus artist Laszlo Moholy-Nagy was involved in the production of the film, although only about 90 seconds of his work wound up being used. An additional four minutes of footage was later found and are presented here. This footage was later utilized by Jan Tichy for a video installation titled Things To Come 1936-2012 which runs for two minutes and thirty seconds.

The final piece is a bit of fascinating audio history. A single-sided 78 rpm, which was used to record some ideas, was found in the collection of a former Korda employee. The scratchy four-minute recording features a reading about the Wandering Sickness, plus notes regarding camera placements and shots for these scenes. The male voice is unidentified.

As Geoffrey O’Brien mentions in his essay included in the booklet, “Whither Mankind?” about Things To Come, “No one who sees it ever forgets it.” I believe that to be an understatement. Only someone with the stature of H.G. Wells could have made this picture, and it is one of the most fascinatingly weird movies ever. The philosophy behind it is basically insane, and the visual depiction of the future is amazing. For anyone with an interest in film history, Things To Come is a must.