”It’s amazing how a few insults can bring people together in three hours.”

”It was certainly good to hear all the names you called me. I haven’t heard ’em since I left Father and Mother.”

Sometimes, I forget that the motion picture industry even had a pre-Hayes Code era, so when a movie from the early ’30s is displayed before my eyes and mentions the (soon-to-be-forbidden) act of fornication between two guys and a gal, I can’t help but smack the side of my head like you would an old tube television that was on the fritz. Shortly after I did a bit of shuffling backwards via the remote to clarify that I did, in fact, rehear the discussion about sex, I had to stop and perform an ocular double take (wherein one blinks twice rapidly instead of doing the head gesture) and say “Wow.” Sure, we’re used to it now, but it’s downright shocking to hear in a vintage movie like Ernst Lubitsch’s Design for Living.

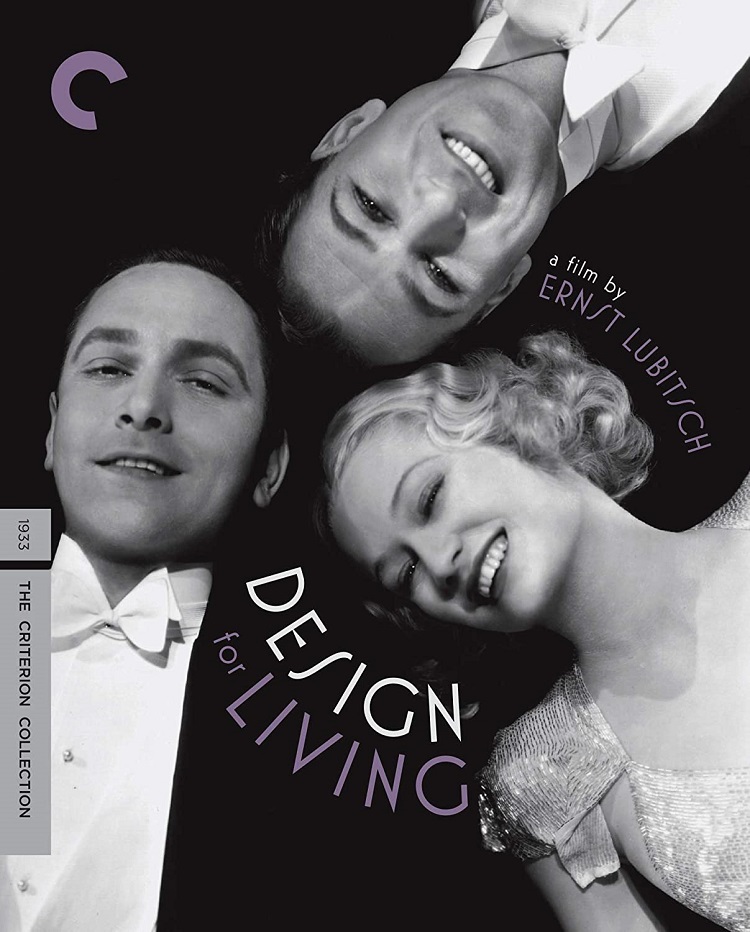

Theatre audiences that had seen the original Noël Coward play prior to the production of this delightfully risqué 1933 comedy were probably surprised more than any moviegoer would have been, as Coward’s stage version of Design for Living (which successfully opened on Broadway earlier the same year) was not terribly shy about the “ménage à trois” factor this moving picture adaptation hardly even implies. Of course, to compare the play with the movie would be wholly similar to weighing in the parallels of palm trees and polar bears: Lubitsch and his handpicked screenwriter Ben Hecht completely rewrote the entire affair. Instead of three upper-class twits, we get a trio of carefree bohemian-esque folks.

We begin with young, beautiful working girl Gilda Farrell (Miriam Hopkins) making the acquaintance of two unconventional, fellow Americans — Tom Chambers and George Curtis (Fredric March and Gary Cooper, respectively) on a train in Paris. Hitting it off almost immediately, the guys and gal form an unconventional relationship, wherein Tom and George each secretly woo Gilda — something that doesn’t settle well with her employer, the very prudish and posh Max Plunkett (Edward Everett Horton), who furtively harbors feelings for the girl himself! When Tom and George discover Gilda has been seeing the both of them clandestinely, they strike up a “gentlemen’s agreement” — to wit they vow to be close friends, but with “No sex.”

Yeah, right.

The Criterion Collection brings us this marvelously suggestive pre-Code romp into the world of complex relationships via an all-new HD transfer taken from a 35mm fine-grain master positive. While time has not been altogether endearing to the source material, Criterion has done a wonderful job eliminating debris and damage here, giving us an all-around first-rate presentation. The original monaural soundtrack is included here in a very crisp and more-than-adequate English LPCM 1.0 form, with optional (SDH) subtitles accompanying. Special features include “The Clerk,” a clip from 1932’s anthology piece, If I Had a Million, directed by Ernst Lubitsch and starring Charles Laughton. There’s also a select-scene commentary with film professor William Paul (author of Ernst Lubitsch’s American Comedy) as well as featurette “Joseph McBride: The Screenplay,” wherein the film scholar discusses the adaptation of the Coward play.

Speaking of Coward, the late great fellow himself is on-hand to introduce a filmed version of his original play in a vintage episode of ITV’s Play of the Week from 1964. Finally, there’s a booklet housed within the Blu-ray’s case featuring a well-written essay by critic Kim Morgan, which rounds out an impressive release of this superbly directed and acted classic.

Highly recommended.