I have no choice but to dismiss you. It breaks my heart, but I can’t expose my guests to your firearms. It may be wrong of them, but they value their lives. – Marquis Robert de la Cheyniest (Marcel Dalio) to his trigger-happy groundskeeper, Edouard Schumacher (Gaston Modot).

Anyone who’s even remotely familiar with the Internet knows that it’s pretty easy to find just about anything you’re looking for — from snow tires to prostitutes. It’s also very common to see something shocking on the ol’ Information Superhighway. Why, within mere minutes of his demise, images of the late Muammar Gaddafi were being spread around the world via phones. The same can be said of movies (though how Gaddafi and cinema play into the same article is beyond me, and I apologize if I’ve already confused you if you found this by typing in “Gaddafi death photos” into your search engine — but, then, you could probably use a little change of pace, so there): you can find almost anything on the ‘Net — providing you know where to look, that is.

You can imagine then what film historians Jean Gaborit and Jacques Durand must have endured in the mid ’50s (when we only had a regular Highway, and not an Information Super one) when they pieced together the nearly-lost 1939 Jean Renoir film, Le Règle du Jeu: a movie that had been heavily cut, banned and bombed on (literally) since its own Parisian premiere by governments — reigning, invading, or otherwise. Scouring all of France, Gaborit and Durand were able to reconstruct about 98% of Renoir’s original cut, and threw in well over 10 minutes of previously unused footage (with Renoir’s approval) to make up for that missing 2%.

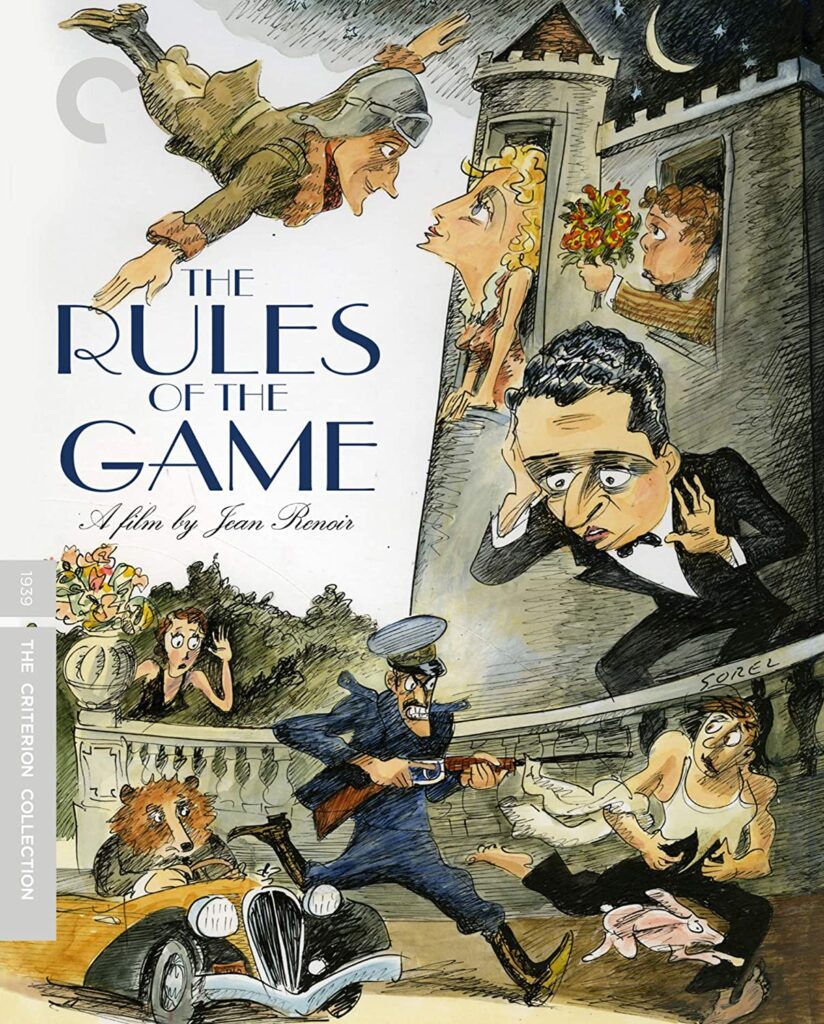

Looking at the feature today, you have to scratch your head and wonder what everyone was so upset about — as The Rules of the Game’s jabs at the elements of high society then are less discordant than anything you can find on YouTube today. The “comedy of manners,” inspired by French playwright Alfred de Musset’s Les Caprices de Marianne, tells of a grouping of French society’s upper crust (and the servants that wait upon them hand and foot) in the days shortly before the start of something called World War II.

We begin with the heroic achievement of André Jurieux (Roland Toutain), who lands his plane before an anxious crowd after flying nonstop across the Atlantic in just 23 hours. Upon learning that his plight of flight has not been exultant enough for Christine de la Chesnaye (Nora Gregor) — the woman he is in love with, and whom he performed the whole daring duty for — to show, he quickly turns into your average, lovesick Frenchman. It turns out Christine is determined to call off her minor (and open) affair with the aviator, an act of adoration towards her quirky husband — Robert, Marquis de la Chesnaye (Marcel Dalio), who collects the world’s most disturbing music boxes — to call of his affair with his mistress, Geneviève (Mila Parély).

Despite the desire to call off their extramarital liaisons, the Marquis and his wife wind up inviting their respective rendezvous cohorts to a grand hunting party at their country estate. Christine invites André at the behest of Octave (Renoir) — who is not only a mutual friend, but was also a close friend of Christine’s father. Geneviève’s invite, however, is entirely her own doing: Robert is too weak to say “No” — and too nonchalant and involved in his own self to really care. Meanwhile, the Edouard and Lisette Schumacher (Gaston Modot and Paulette Dubost, respectively), who serve as the groundskeeper and maid, endure an ordeal of their own when a flirtatious poacher (Julien Carette) sticks his nose into their marriage by trying to stick his tongue in Lisette.

It’s hard to believe, but things get even more complicated from there. As I had mentioned before, it’s almost bewildering to think this movie ignited the indignation of the masses upon its release — what with the numerous mind-numbing television shows today that depict such things as cheating spouses in a celebratory light. That said, however, it only takes one viewing of Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game to see something that even the least-nauseating reality TV shows could never ensnare: heart. Their individual peculiarities and/or prejudices notwithstanding, the characters here are deeper than the Mariana Trench — something only a master like Renoir could both conjure and capture amid the movie’s many moments of comedy and drama alike.

Previously released by in 2004, The Criterion Collection gives The Rules of the Game a High-Definition upgrade in a presentation that makes it hard to believe the print used in this transfer was reconstructed from numerous elements. Sure, there’s some grain here and there — as well as some wear and tear — but that’s to be expected considering the film’s history. The movie is presented in a pillar-boxed 1.33:1 aspect ratio with a crisp and clear monaural French soundtrack with removable English subtitles. The remarkable outcome Criterion has given us is commendable for that reason alone, while the assortment of special features only adds to the remarkableness.

The bonus materials, all of which were included in the 2004 Standard-Definition release, beginning with an audio commentary written by Renoir scholar/associate Alexander Sesonske, which is read by filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich; an introduction by the late Monsieur Renoir himself (which was filmed in the ’60s); and comparisons of the various cuts of the film by historian Chris Faulkner. Additional features include a chapter from the 1966 French television series Cinéastes de Notre Temps wherein Renoir is interviewed by filmmakers Jacques Rivette and André Labarthe; the hour-long introduction of David Thompson’s BBC documentary on Renoir; and assorted other bits and pieces about the production of Le Règle du Jeu — including a 40-page booklet by Alexander Sesonske.

Highly recommended.