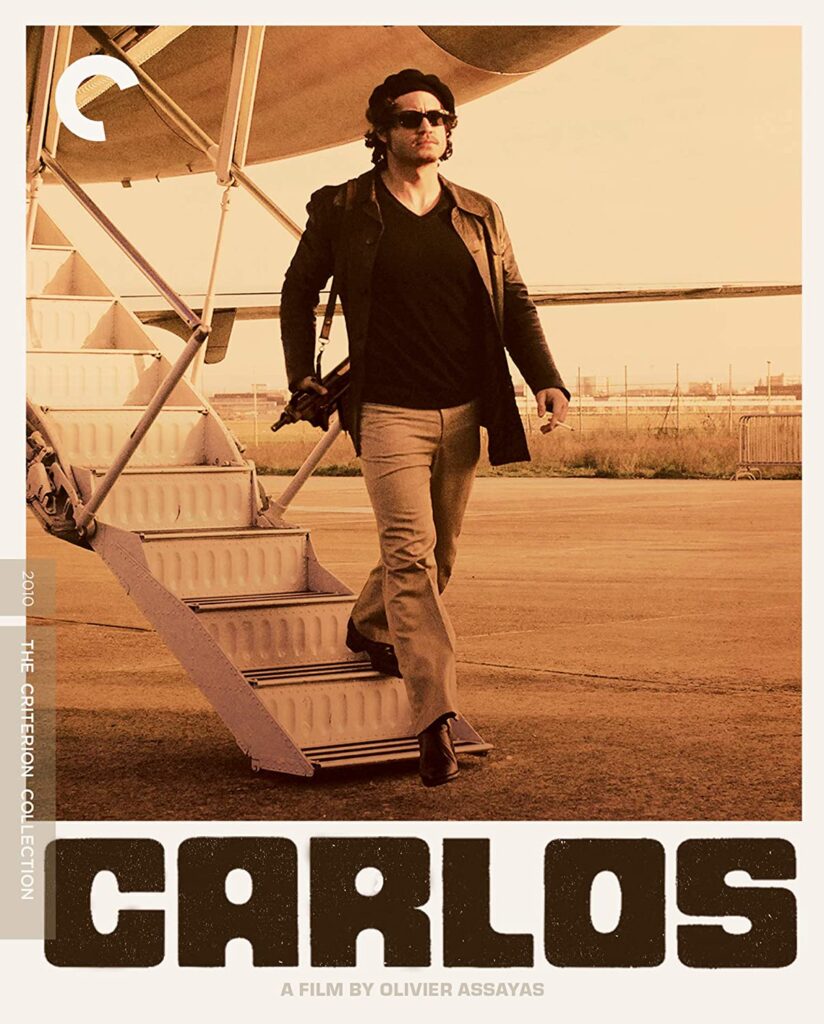

From the opening explosion of a car bomb in Paris, through the anti-climactic, somewhat pathetic ending – Carlos is a 330-minute tour de force of a film. French director Olivier Assayas’ epic treatment of the life of terrorist Carlos The Jackal has been released in a variety of forms. These range from the full theatrical and TV miniseries all the way down to a 185-minute edition shown in German theaters. As a part of The Criterion Collection, Carlos is now available in a definitive, director-approved four-disc package.

Although there is a prominent disclaimer at the top of the film stating that it is a work of fiction, this is mainly cover. The amount of research that went into Carlos is staggering, and the onscreen results speak for themselves. Assayas uses a mix of newsreel footage, and his own recreations of events to tell his story. Sometimes the two are hard to separate. For example, during a press conference regarding the OPEC ministers hostage crisis, Assayas uses actual footage, into which he has superimposed his own actor as Austrian chancellor Bruno Kreisky.

Although largely forgotten in the post 9/11 world, Carlos was once the most feared terrorist in the world. Ilich Ramirez Sanchez was born in 1949 to staunch socialist parents in Caracas, Venezuela. As Assayas makes abundantly clear, he was a Baby Boomer of a very different stripe.

As portrayed by Edgar Ramirez, Carlos was a mix of contradictions. At times his fight for noble causes seems like nothing more than an excuse to gain personal glory. Early in the film, his self-absorption is fully evident. After carrying out his first hit, we cut to the man admiring his nude figure in a mirror. The physical manifestations of his decadent life are fully evident as well, as Carlos gets fat and bloated as time goes on.

As a budding “star” on the mercenary stage, Carlos is involved in a number of high-profile actions. He joins a wing of the PLO in the early seventies, where he is trained in guerrilla warfare, and was given his nickname. Curiously, he is never once referred to as Carlos The Jackal in the film.

The pivotal action Carlos and his supporters engaged in was the December 21, 1975 OPEC ministers hostage-taking in Austria. This commanded the world’s attention like nothing else he ever did. While the events themselves are a matter of history, the subtext of a post-sixties disillusion with the world is not. Carlos and his band of rag-tag accomplices are shown in a much different light than we are accustomed to. Even though the group ostensibly “wins” by being given $15 million dollars to free the hostages, the cries of “sell-out” within his own camp are deafening. Carlos The Jackal’s name has been splashed in headlines around the world, but he begins to act more like a spoiled rock star than anything else.

The hour-long OPEC sequence is the fulcrum of the film, and plays out as a movie within a movie. The ease with which this small band of self-styled revolutionaries take over the OPEC headquarters in Vienna is hard to believe today, yet it happened. What the director captures best is the mix of arrogance, fear, personal betrayal, sacrifice, and finally futility in all of this. Carlos is faced with a series of moral choices in regards to a wounded comrade, and the ultimate outcome of the action. To say that he fails every one of these tests miserably in the eyes of his supporters is putting it mildly.

OPEC reveals the emperor’s new clothes, and as the seventies crawl into the eighties, Carlos is marginalized more and more. An ugly manifestation of his decline is his treatment of women. Never one who might be considered enlightened towards his wives and girlfriends, Carlos becomes despicable as time moves forward. He treats the females in his life at best as prostitutes, and at worst with outright hatred. This is most graphically portrayed with the mother of his only child, who he abandons as cavalierly as a spent bullet casing.

Carlos has been described as the best film ever made about terrorism, and there is ample reason for that assessment. For one thing, the five and a half hour running time is completely justified, there are no dead spots. When I first sat down to watch it, I really did not think I would be able to view it in one sitting. It is an awfully long time for a film after all. But my attention never wavered, which is a testament in itself as to how engaging this movie remains all the way through.

In many ways, Carlos is bravura filmmaking. Olivier Assayas makes no concessions in telling his story. The mix of various sources is one thing, but the dialog is another. Carlos spoke five languages, and all are used here without hesitation. If there are an abundance of subtitles, then so be it.

The use of music is another area where Assayas refused to compromise. Although for the majority of the time periods represented, the post-punk sounds of New Order, Wire, and The Feelies are inaccurate – but their use work spectacularly well. The nervousness inherent in these instrumental bits complements the action perfectly.

As a Criterion Collection feature, Carlos devotes a full DVD exclusively to bonus features. These include two fascinating films in and of themselves. The first, Carlos: Terrorist Without Borders, is an hour-long documentary. The second is Maison de France, another documentary on a bombing which was not included in the film. There are interviews with Olivier Assayas, Edgar Ramirez, cinematographer Denis Lenoir, and former Carlos associate Hans-Joachim Klein. Criterion has also included a twenty-minute documentary on the filming of the OPEC raid, as well as commentaries, and a substantial booklet with essays by Colin MacCabe and Greil Marcus.

Carlos is an extraordinary movie, in every sense of the word. Like The Jackal’s car bombs, it easily could have exploded right in Olivier Assayas’ face. The fact that he manages to hold everything in place for 330 minutes is an achievement in itself. But to be able to make this subject matter so intriguing, without ever pandering to the lead is something else again. This is a remarkable film.