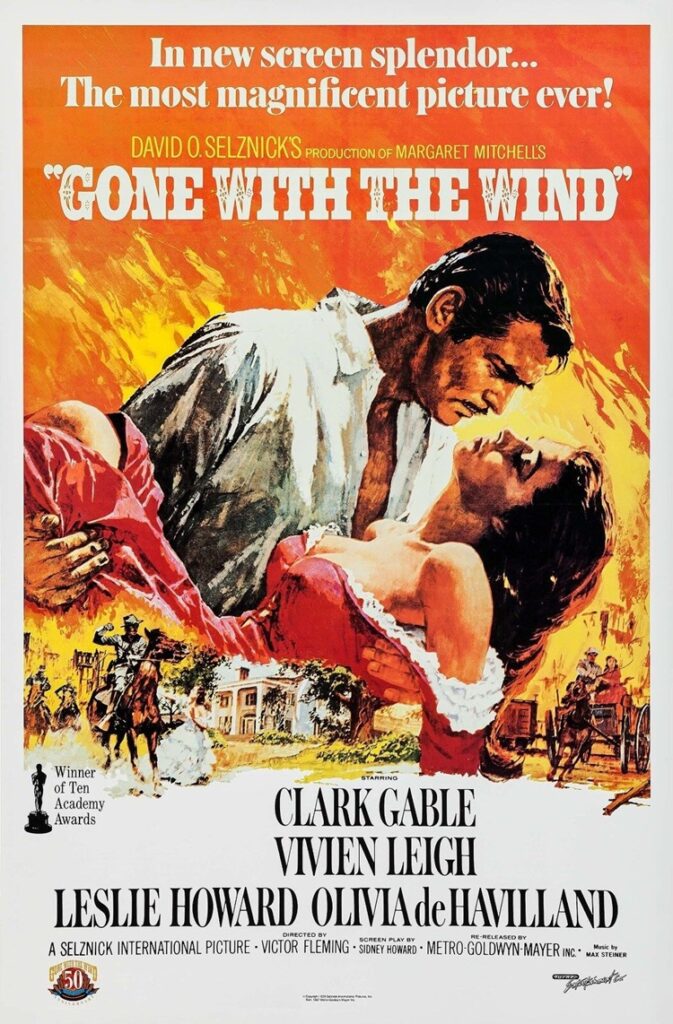

Victor Fleming’s Gone with the Wind (1939) is the filmed version of one of the most popular novels ever written in the English language, Margaret Mitchell’s impressively popular book of the same name from 1936. At the twelfth Academy Awards, Gone With the Wind was nominated 13 times, and won 10 awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actress for Vivien Leigh. Keep in mind that during the same year, Stagecoach, Ninotchka, and The Wizard of Oz (also directed by Fleming) were simultaneously up for best picture.

Buy Gone with the Wind (70th Anniversary Edition) Blu-rayAs the movie opens, Scarlett O’Hara (Leigh) is concerned with purely Southern girl things. Who is she supposed to marry now that the dreamy Ashley Wilkes (Leslie Howard) is planning on marrying his cousin, Melanie Hamilton (Olivia de Havilland)? There is a barbecue tomorrow: who will Scarlett allow to sit with her, dance with her, bring her dessert? Upstairs at the party, Scarlett is pouting because she is forced to take a nap; downstairs, the men are discussing the pros and cons of Civil War which will begin in mere days.

Once the war begins, and Scarlett knows she has lost Ashley to Melanie, Scarlett instantly gets engaged to Melanie’s younger brother, Charles (Rand Brooks), in hopes of eliciting any sort of feeling from Ashley. Poor Charles, though, is dead of pneumonia almost before the scene can change. Scarlett is sent to the Hamilton home in Atlanta where she attends a charity bazaar and wears mourning attire while waltzing with Rhett (Clark Gable), who now works as a blockade runner for the Confederate States of America. For the most part, the untimely death of her young husband, Charles, is the happiest time of Scarlett’s short, so-far, life. From here on out, nothing will seem to go well for “poor” Scarlett.

So much is working in Gone With the Wind that it becomes hard to sing all of its good graces. The actors, especially Leigh and Gable, are wonderfully cantankerous and bossy to each other. There is a sexual disparity between the two that would stay uneven if Leigh weren’t such a, well, firecracker. The music by Max Steiner and cinematography by Ernest Haller and Ray Rennahan are, of course, top notch, and the burning of Atlanta scene packs as much punch as it ever has. In no way is this a film that is feeling its age. It is a long film, and every frame, every burst of music, every aptly delivered line causes one to be enraptured.