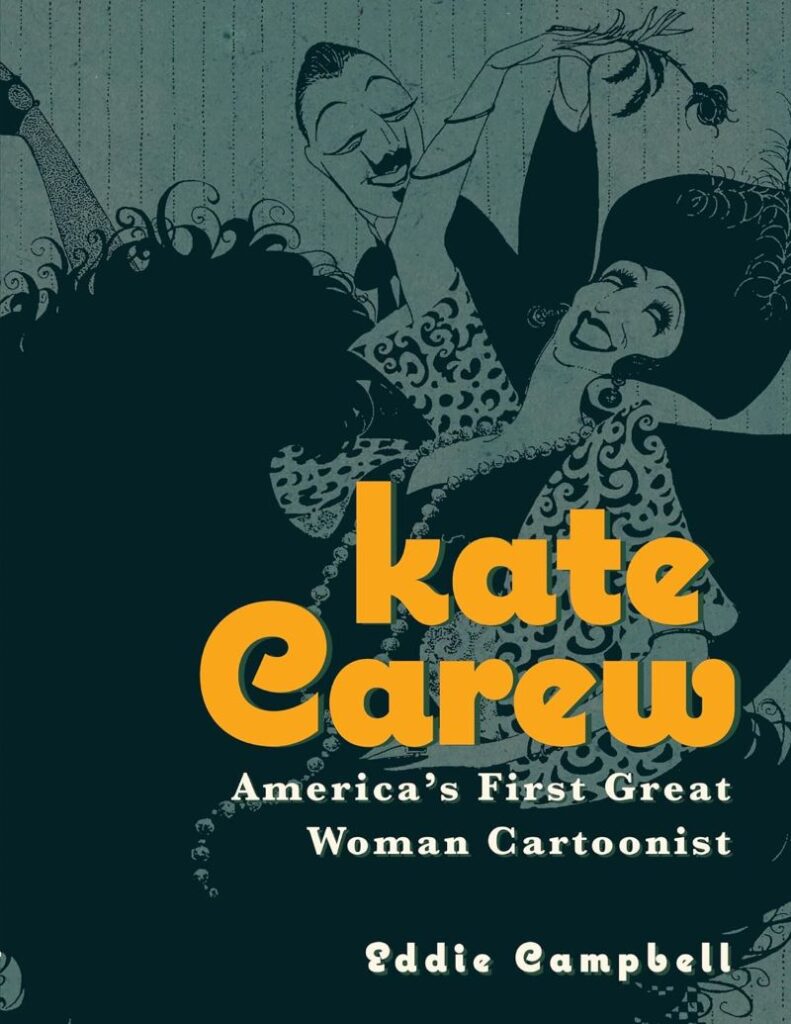

At the start of the 20th century, when female employment of any kind was a rarity, Kate Carew was an absolute unicorn as a trailblazing newspaper cartoonist. Starting from illustration assignments, she eventually shifted into comic strips and illustrated interviews with famous subjects. Recognizing that most people have never heard of her, fellow cartoonist Eddie Campbell (From Hell) has compiled this richly rewarding new overview of her life and works.

Buy Kate Carew: America’s First Great Woman Cartoonist bookComing from Fantagraphics, readers may assume that the book is primarily a collection of Carew’s comics and illustrations. While the visual collection is present, it’s interspersed between Campbell’s exhaustive biographical text about Carew’s life and career. This results in a book that feels more like an illustrated biography than an art compilation. Campbell has been down this road before, most notably in his book about Jack Johnson and early comic strips (The Goat Getters, also from Fantagraphics), making him uniquely qualified to take another trip through decaying and disappearing newspaper archives circa 1900.

It’s clear that Campbell took a deep dive into Carew’s past, striving to unearth and present the most comprehensive and definitive appreciation of her work, a goal he very much achieves here. He was assisted by Carew’s granddaughter, Christine Chambers, who provided him with unprecedented access to archival material and her own childhood memories. She recounts how she viewed Carew as just a typical grandma, with assorted paintings around the house offering no clue that Carew was a trailblazing newspaper contributor with decades spent in the public eye.

While Carew’s total comics output was fairly paltry, mostly confined to one short-lived weekly strip, her innovative approach to illustrated interviews of famous subjects clearly drove the graphic-arts medium forward. Among her notable newspaper interview subjects were the Wright Brothers, Jack Johnson, Picasso, and Mark Twain, with her sketches helping to bring their likenesses into the country’s living rooms before newspaper photography was viable. She also incorporated herself into the interview sketches, drawing a comically wide-eyed avatar called Aunt Kate who became her most recognizable calling card. This unique mix of actual famous figures, fictionalized cartoon interviewer, and humorous interview text marked a defining moment in both journalism and comics.

It’s interesting to note Carew’s change in styles as the years and newspaper technology progressed, moving from heavily cross-hatched realistic drawings to comical “big head” caricatures to charmingly cute comic strips to the assured, expressive clear line of her illustrated interviews. She spent her later years largely abandoning ink, focusing instead on painting for her own amusement as she shifted her style yet again. This vast array of artistic approaches makes it difficult to identify her signature style, but also highlights her impressive range and ability to adapt to shifting market dynamics and her own changing interests.

Even if you’ve never heard of Carew, Campbell’s book is an incredibly well-researched piece of investigative journalism guaranteed to make you a fan. Aside from her own struggles as a female artist in a male-dominated newspaper world, the book is also an illuminating look back at the progression of the print industry and the notable figures of the time who are still famous today.