When presented with a new Hollywood memoir by lauded playwright/screenwriter/director David Mamet, one might logically expect the results to follow one of two paths:

- A chronological journey through his full Hollywood career, tracking the highs and lows from production to production

- A selection of focused essays delving into specific facets of interest regarding his process, collaborators, and lessons learned

This book is neither of those options. Instead, we are presented with a meandering missive that is at times a Festivus-like airing of grievances, a stream-of-consciousness string of brief and frequently contextless industry anecdotes, and random asides that have nothing to do with the film industry. Even within individual “essays”, his attention is so fractured that he hops from one train of thought to a completely unrelated wisp of an anecdote to another, with no apparent point to be gleaned. Thus, the reader’s enjoyment is inherently tied to just how much unfiltered Mamet one can tolerate.

Mamet has written far more non-fiction books than fiction, and in fact has covered his perception of Hollywood previously in other books, including the closest comparison, Bambi vs. Godzilla: On the Nature, Purpose, and Practice of the Movie Business (2007). However, the hook here is meant to be that he has reached the end of his film career, and so has no remaining reservations about burning down the mechanism that kept him gainfully employed for so many decades. If only it were that simple. Rather than take direct aim at any named parties that have aggrieved him, he deals in a frustrating style of generalities, alluding to abusers rather than calling them on the carpet. For example, on agents: “the truth is, if you’re hot you don’t need an agent; and if you’re not, the agent doesn’t need you.”

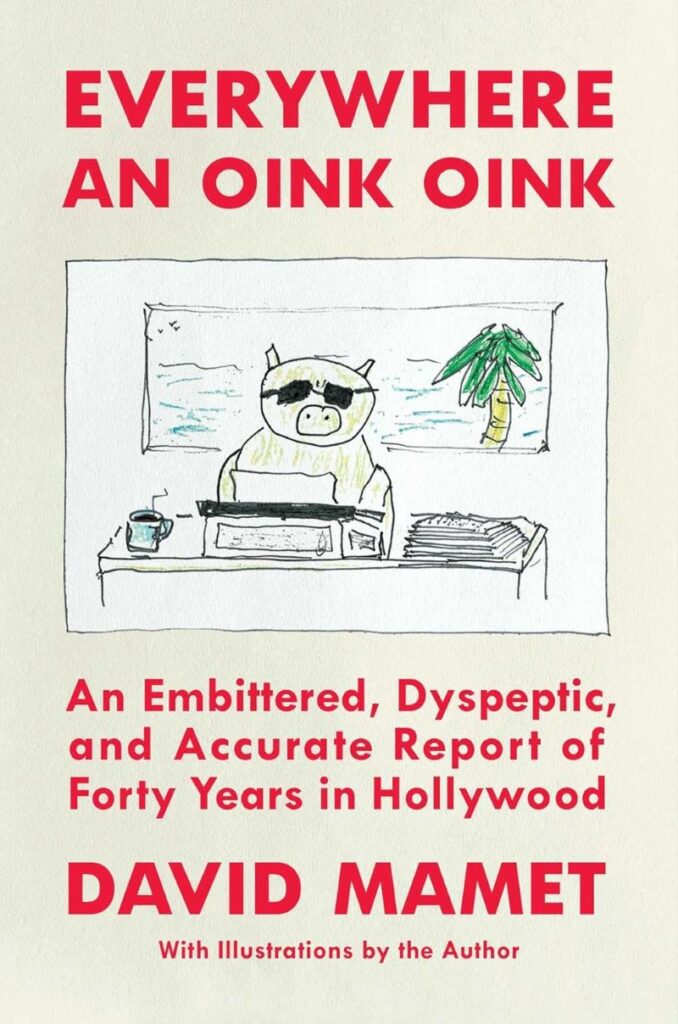

As for his accompanying illustrations: as an artist, he’s a great writer. The general format looks like rough drafts for The New Yorker one-panel gags, as drawn by an elementary school student. None of them are particularly funny, and are usually more groan-inducing, like his pitch for Gandhi II: “He’s back! And he’s more at peace with himself than ever!” I won’t even recount what P stands for in his bawdy Cookie Monster gag.

And yet, there’s still some entertainment to be had here, much like one looks forward to the politically incorrect bombs dropped by grandpa at Thanksgiving dinner. Mamet has two primary foes that he returns to over and over throughout the book: producers and diversity. In his mind, producers are all idiots who know nothing about movies and ruin everything they touch. Unfortunately, he’s not naming names. More bizarrely, he repeatedly takes aim at the rise of diversity in casting and every other department in Hollywood, blaming color-blind employment for ruining otherwise fine productions. He touches on his conservative politics contributing to his fall in Hollywood, and if this is his hot take on diversity, I can understand why. While never explicitly labeling himself a Republican, his book comes perilously close to wearing a MAGA hat.

After reaching the age of 75 while writing this book, Mamet fully comprehends that the youth- and progressive-obsessed film industry has left him behind. In one of the most telling passages, he laments that he is “now the Hermit of Santa Monica, shunning a world that has moved on, and to which his name is as the mention of Herodotus to illiterate youth.” He mourns the loss of departed friends, especially actor Ricky Jay, much as he mourns his obsolescence in an industry that aspires to no longer tolerate the racist and sexist environment he came up in. His favorite topics in the book turn out to be second-hand tales of Hollywood lore from long before he even entered the scene, revealing his longing for the good old days that are never coming back.

At just over 200 pages including illustrations, Mamet’s book is a breezy ride that can be comfortably completed in a few hours. While his afterword thanks the editors at his publisher, there’s very little evidence of any real attempt at editing his jumbled torrent of text. Only a couple of essays around the midpoint settle into any cohesive flow, with the rest a scattershot assemblage of whatever crossed his mind at any given moment. While it’s refreshing to have a product that is very clearly unfiltered, and Mamet is known for his uncompromising vision, this is one case where some custodial assistance could have benefited the work. As it stands, we’re left with the ramblings and grumblings of a legendary talent as he watches the sunset of his career.