The first couple minutes of Mind Game contains, after a brief scene of a girl being chased onto a subway train and getting her leg caught in the door, a montage. It lasts a couple of minutes, and contains scenes from various lives, put together without context, without any real sense of which character is which, who is who or when or where. Segments from TV shows are interspersed with scenes from daily life, and memories that are later shown to be incomplete.

A similar segment plays at the end of the film, and while most of the context for who, what, and where has been filled in, it’s still a mind-boggling cascade of information. Mind Game is an animated film from Japan directed by Masaaki Yuasa, who recently helmed the Netflix-original anime Devilman Crybaby. While anime literally just means animation from Japan, it carries with it certain expectations and limitations (particularly in character design) that are too cramped to contain a film of Mind Game‘s scope.

The story centers around a young lay about in Osaka, Nishi, who wants to draw manga, and who wants to win back the heart of Myon, the girl he’s been crushing on since he was a kid, but who just told him she’s getting married. He meets the fiancé at Myon’s family restaurant, where her sister Yang is working behind the counter. A pair of yakuza come in (men we saw chasing Myon to the subway at the very beginning of the film) – one of whom is a deranged soccer fanatic who beats up Myon’s fiancé, threatens to rape Myon, and eventually jams his gun in Nishi’s butt and blows his brains out, literally.

Nishi goes into an afterlife, meets a continually shape-shifting God, and while he’s told to go into a portal and disappear, he goes the opposite way. Time reverses, he gets the gun (ingeniously grabbing it with his glutes) and turns the table on the Yakuza. Then he, Myon and Yang go on the run in the yakuza’s car, and after a long car chase… end up eaten by a whale. Life in the belly of the whale takes up most of the rest of the movie, where they meet an old man who has been there for 30 years.

Retold thus, it seems a strange but straightforward story. But Mind Game is anything but straightforward – narratively, visually, tonally, Mind Game is constantly shifting, every scene packed with odd, seemingly meaningless details that connect to other seemingly meaningless details in seemingly unrelated scenes that come together in a tapestry of almost dizzying complexity.

The anarchic visual style is the most immediately obvious departure from most anime, and most animation. Most of it has a scruffy, sketchy quality – anime tends to have strong line work and very clearly defined (if rarely very distinctive) character design. Mind Game‘s characters have more in common with the lumpy pencil-work of Bill Plympton. Close-ups on faces are sometimes rotoscoped photographs, other times the blanker, simpler designs of more traditional anime styles. The visual style is continually shifting, often several times in the same scene. There’s a love scene in the film where the two characters intertwine, their bodies distort into all kinds of different combinations of insect parts or tentacles (though not in a Cronenbergian-body horror sense) as they crawl up ceilings and fly through the sky in the throes of their passion. Sometimes, they are just meshes of messily brushed paint.

The danger of this sort of wild visual experimentation is that it can all be done for its own sake, without much to back it up in terms of story or theme, just animators making random shapes for their own amusement. The first time I watched Mind Game that seemed to be the case. There was so much happening on the screen so often that it felt less like a feature film and more like a 100 minute audition for an animation studio. On subsequent viewings it became clear that much of what seemed random was actually considered – entire sequences of the film that have nothing to do with the plot do have to do with the development of the characters, even if the film never explicitly puts the connections together. That’s the audience’s job.

Thematically, the film is about appreciating life. Understanding the small things that exist all around one are little miracles of someone else’s hard work. Introspection can only get one so far, and eventually one has to connect with the outside world with courage. But like everything else in the film (except for that ever-changing visual style) it’s not laid on too thick nor explicitly mentioned. Mind Game is a mind-bender. It rewards patience and careful watching, even as it makes that sort of watching challenging through its kaleidoscopic visual and narrative.

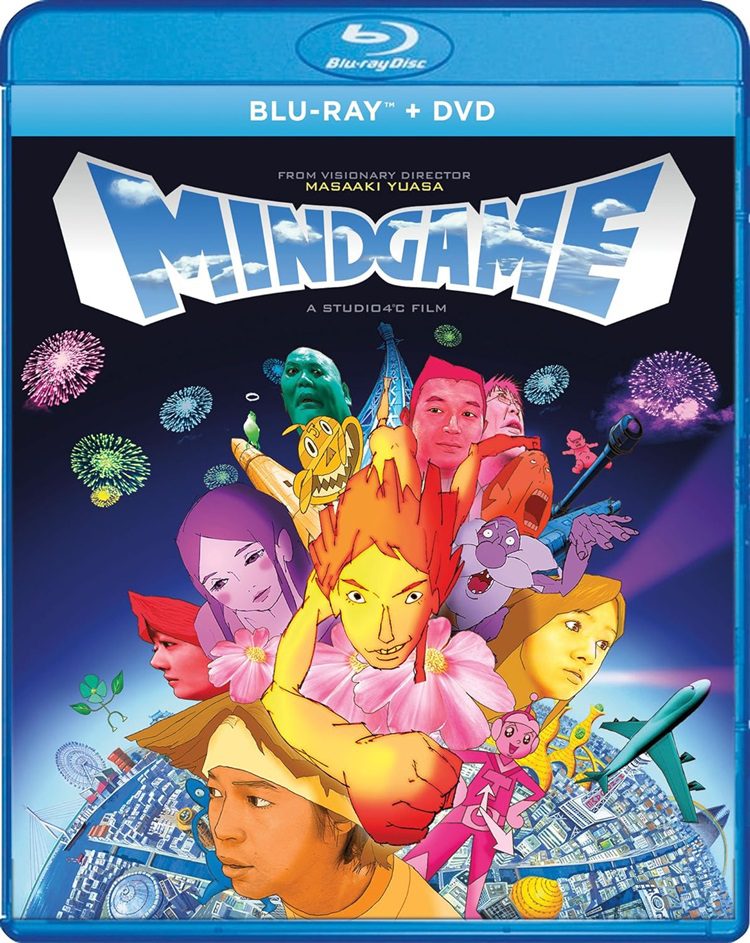

Mind Game has been released on DVD and Blu-ray by GKIDS, a label that has been doing yeoman’s work getting classic anime films onto American stores. The film has only Japanese audio, with subtitles available in English and French. It’s unrated, but definitely not for kids. The extras include the film’s trailer, production galleries, and a feature-length animatic, which is the preliminary test animation and storyboards that precede that actual finished animation. Most illuminating, it includes 30 minutes of commentary by director Masaaki Yuasa on a small selection of scenes. This is a unique commentary, since the director is going through the scenes, usually not being played at full motion, while he describes both what’s going on and his intent, sometimes winding the footage back to make his points. The commentary made clear to me that there’s a lot happening on screen that simply doesn’t translate to English. It’s too dense. It also made clear what I had begun to suspect from my later viewing, that the apparent randomness on screen was actually planned, considered, and relevant.