Michael Zahs, a retired history teacher and the subject of the new documentary Saving Brinton, is the very definition of someone who is a gentle giant. His large stature and lengthy beard give him a rather intimidating appearance, but when you hear him speak and get an insight into his life, he’s a lovable teddy bear. He’s the kind of person from whom you could learn a lot, and not just because he once taught history in high school.

As we get a look inside his home in Ainsworth, Iowa, we see that he loves to collect things. It has gotten to a point in which just about each corner of his home is covered with some type of artifact he found and took into his possession. To many, a lot of the stuff Zahs owns could be considered junk. They have no value to them, and they don’t see the point in keeping it around. But Zahs sees each item as having a value of some kind to someone, and he’s hoping that at least one other person will find it as interesting as he does.

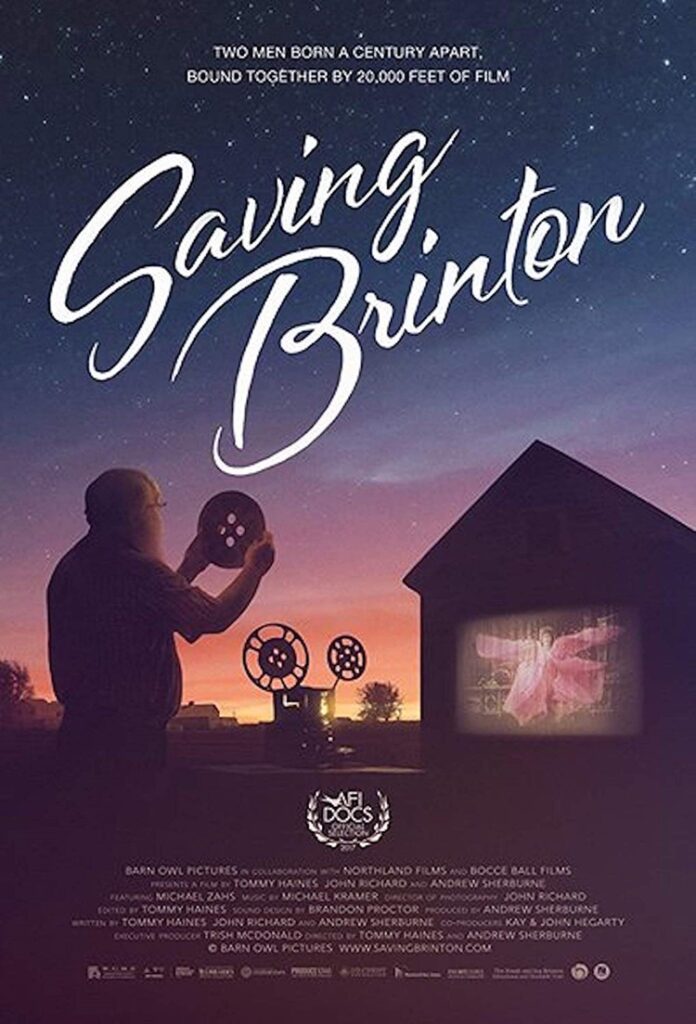

Saving Brinton looks at a particular moment when Zahs comes across some old nitrate film reels in a farmhouse basement. The most significant thing about these reels is that they were amongst the first moving pictures to be introduced to the world. A lot of these early motion pictures are long gone due to decay or catching on fire, so Zahs’ discovery is a wonder to behold. And if it wasn’t for his finding, this collection was scheduled to be sent to the dump.

The person to whom these reels belonged was one Frank Brinton, who, during the early 1900s, traveled throughout the Midwest showcasing these films and introducing them to the cinema world, which was in its very early stages. Some of the films that Zahs came across include footage of President Teddy Roosevelt and two short features from Georges Méliès that were thought to have been lost to history. Not only does Zahs come across these reels, but he also comes across the projector which Brinton used to show the images. As he exclaims in one scene, “This is pre-movie.”

His passion for things of the past is felt in Saving Brinton. To whereas many people might call him a “collector,” he prefers to be called a “saver.” Throughout his life, he has learned how to save everything. Part of the tour of his house includes showing the room that contains all of his tools for building log houses. It’s truly fascinating to see how much stuff he has, and how dedicated he is to making sure it finds a home.

The Brinton collection came into his possession just three days after he and his wife were married in 1981. It takes up an entire room, and, for years, has been sitting there in the hopes that someone else will find value in it and keep it somewhere for preservation. Although Zahs has held annual festivals in the small town of 600 people since 1997, he sees that this material could capture more interest if he could just find the right people who will take good care of it. It’s not until 2013 that someone’s interest is captured, and Zahs’ story becomes internationally known. His collection of Brinton material, which also includes old posters and catalogs, garner the attention of the Special Collections department at the University of Iowa, the Library of Congress, and a Méliès expert in France.

It’s important to preserve the past for generations to come, and when they look back and see how certain things evolved, they, too, can be fascinated by it all. Saving Brinton doesn’t force its message down the viewer’s throat, but, rather, it graciously states how important it is to not let things be lost to history. We may be able to read about it, but to see something that was from a certain period is more intriguing. This is why it’s great to have people like Zahs exist, so that they can hang onto something until someone finds a way to properly preserve it.

Saving Brinton does lose some focus when it tries to become a more detailed profile of Zahs by showing him going to visit his ailing mother or hosting a class reunion. I understand that filmmakers Tommy Haines and Andrew Sherburne were trying to capture his spirit and how much of a kind-hearted and devoted person he is outside of his collection, but these moments don’t feel like a natural fit for the documentary’s overall message. Aside from that minor gripe, this is a charming documentary that will please those who love cinema and those who love preserving history.