There is a scene relatively early in Fernando Di Leo’s classic polischietti Caliber 9 that fairly well sums up everything the film is trying to do. Ugo Piazza (Gastone Moschin) has just been released from prison after doing three years of a four-year sentence. He is immediately accosted by Rocco (Mario Adorf), top henchmen of the Americano’s (Lionel Stander), one of Milan’s mob bosses . They think he stole $300,000 from them just before he got sent to the slammer. The police give him a hard time, too. Just on general principle.

The scene in question finds Ugo at his former Godfather Don Vincenzo’s (Ivo Garrani) apartment asking for a loan to pay the hotel he’s staying at for damages. Damages inflicted by Rocco and his thugs. Vincenzo agrees and has his right-hand man, Chino (Philippe Leroy), give him 100,000 lire. At that moment Rocco busts in, takes the cash off of Ugo, and tears it to shreds. This causes Chino to start punching Rocco’s men. Then Ugo starts punching. When Rocco tries to tell Chino exactly who he is, Chino announces that he already knows, then he says his name. Vincenzo might not be the boss anymore, but his name still carries weight. Then Chino lays down the law. It is against the rules for Rocco to bust into Don Vencenzo’s home. And tear up the money given to their friend. He demands Rocco give Ugo another 100,000 and then politely demands he and his thugs hit the road. Rocco does exactly that, but then immediately runs to The Americano and tells his tale.

So much of Caliber 9 is about how the old way of doing things continually bumps into the new ways. Don Vincenzo and Chino come from a world run by the real mafia, where there were rules and people lived by a code. At one point, Venenzo laments that those days are over, that what exists now isn’t the mafia but varying gang factions. The new boss doesn’t care about the rules. In fact, when he learns of how Chino treated Rocco he demands an apology from Rocco.

The police force is also shifting. The Commissario (Peter Wolff) complains about how Ugo got out of prison a year early, pardoned for good behavior, and how the entire prison system has grown soft. He whines that they are now only allowed to obtain evidence, but interrogating suspects is now left up to the judges. But newly appointed Vice-Commissioner Mercuri (Luigi Pistilli) disagrees. He believes the Americano is but a symptom of a greater social ill, one that is perpetuated by the rich and powerful (and who work without harassment from the police).

I don’t want to get too lost in the weeds of the political subtext of this film, but at times it is almost text, and therefore important to at least mention. The film was made during a period of great upheaval in Italy, sometimes called The Years of Lead. Fanatics on both the left and right sides of the political spectrum committed great acts of violence. The American political machine worked diligently behind the scenes to ensure Italy didn’t become communist (there’s a reason the mafia boss is an American). In the middle of all of this were the people. Average Italians just trying to get by. So it is with Ugo. Sure he was a gangster, but the film goes to some lengths to show us he had no other choice. When you are stuck in poverty, and the government offers no assistance, it is hard not to turn to crime. But now Ugo wants to just be left alone. But he is constantly harassed by both the gangsters and the cops.

Fernando Di Leo directs it like a hard-boiled action film. It begins with that bag of $300,000 going through a series of hand-offs – from a man on a train to a woman in a church square to another man on a subway car. All of this is done in broad daylight, yet another symbol of how times have changed (crime is done in the open now, not in secret and in the dark). When Rocco finally gets the bag, he finds it full of blank sheets of paper cut into the size of dollar bills. We then see him run to each person who handled the gag (except for Ugo who has already been arrested for another crime at this point) and beat the living crap out of them. He finishes them off by tying them up and blowing them to smithereens with some dynamite.

The film rushes from scene to scene, only stopping occasionally to take in the sights (or to leer longingly at Ugo’s girlfriend Nelly (Barbara Bouchet) do her go-go dance routine). But mostly it is a car chase, or a shoot-out, or a bit of fisticuffs. So while there is plenty of political subtext going on, if you are just interested in some good old action, you’ll get plenty to see here.

Personally, I found all the politics really enhanced my second viewing of the film. The action is great, but getting a feel for what the film is saying about not just Italy in the early 1970s but how society is constantly progressing and battling it out between the old ways and new, really deepened my movie-watching experience.

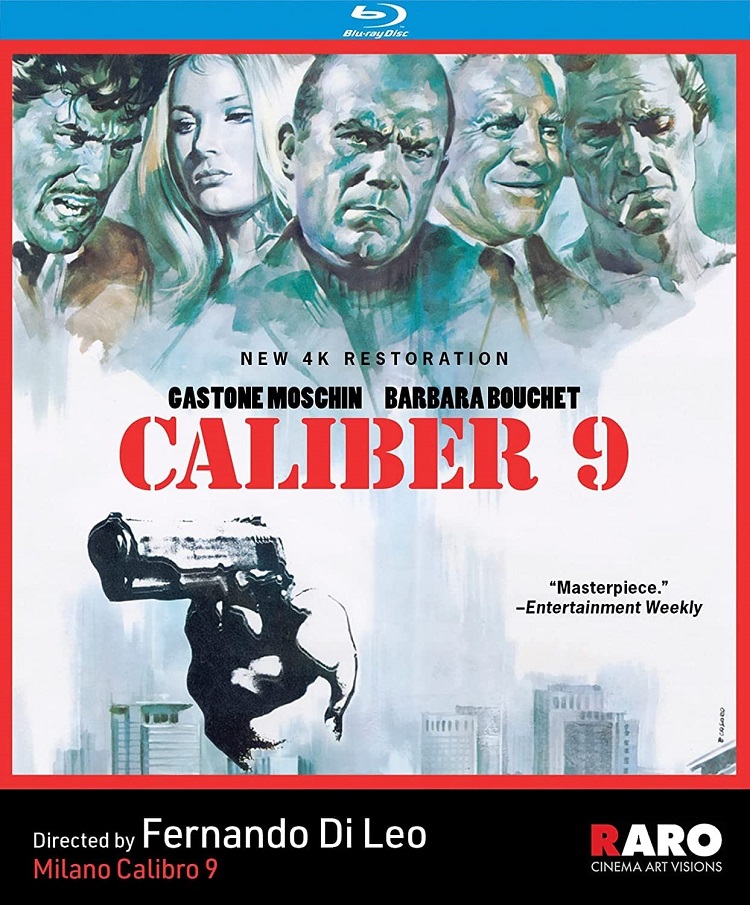

Raro Films in conjunction with Kino Lorber presents Caliber 9 with a restoration that was completed in 2022 and it looks terrific. Extras include an audio commentary from film historian Rachel Nisbet, an alternate English language track, a making-of documentary, a couple of features on Di Leo and Giorgio Scerbanenco who wrote the book the film is based upon, and some still photographs.