Written by Kristen Lopez

Seven years have passed Wes Anderson’s fantastic Fantastic Mr. Fox, the last time a work by author Roald Dahl was adapted for cinemas. And even more time has passed since director Steven Spielberg created works for children. Dahl and Spielberg should equal success, so then why is The BFG so paint-by-numbers? Held up alongside past Dahl adaptations, Spielberg’s formulaic presentation loses the novel’s sense of quirk. Though the source material doesn’t yield itself up to an utterly terrifying feature, a la The Witches, the entire affair will appeal to young children, and young children alone.

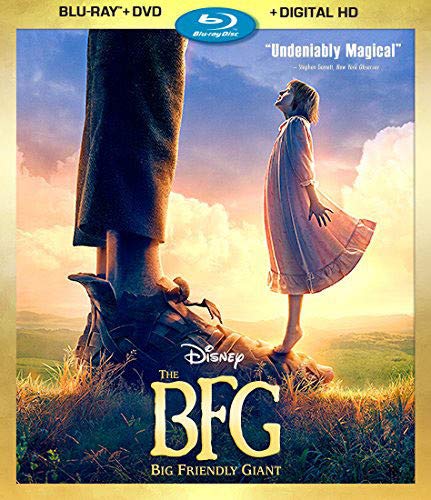

Sophie (Ruby Barnhill) is a young orphan desperate for a friend. Up late one night she discovers England is visited by a “big friendly giant” (Mark Rylance) who takes Sophie back to Giant Country. Once there, Sophie discovers the BFG is responsible for putting dreams into people’s heads, but her dream soon turns into a nightmare when the other giants discover her presence and are intent on eating her.

All of Dahl’s films are silly on the surface as a means of worming morality tales and/or championing the unexpected in the average into children’s heads, whether it’s Charlie Bucket’s goodness in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory or Matilda’s intelligence in Matilda. More pressingly it’s impossible to separate The BFG from the recent Brexit decision, with England leading the charge here to unite countries against the giants, making it rife for think pieces. Spielberg’s basic message is embracing the sense of unity and believing in the impossible, but it sounds, because it is, very generic.

Despite the film’s whimsical storyline and expert set-dressing, the characters are ciphers – representations of whimsy and fun without any depth. We’re told Sophie is an orphan who hates her orphanage for reasons we’re meant to infer because of her “orphan” tag. Sophie is a blank canvas no one though to write anything on, a character we’re meant to read as possessing all the traits of every orphan in pop culture, formed and written in the moment. Almost immediately she’s kidnapped by the BFG and the film meanders in search of a story upon their arrival in Giant Country. Sophie takes to the giant immediately as a means of escaping the horrid life we’re, again, never privy to, while the BFG’s outcast status among the giants and his job of collecting and dispersing dreams is revealed.

Emotion is on the fringes, but it’s never more than illusory. Sophie’s dream literally sits in a jar waiting to be opened, but what that dream is never properly develops. Unlike that other famous orphan, Annie, Sophie doesn’t dream of a family, but what does she dream of? Friendship? The BFG certainly desires a friend, evidenced by clothes from past child companions. Sophie isn’t the first kid to enter Giant Country, but what should be an emotionally poignant moment – that of the revelation of what happened to the BFG’s last companion whom, not surprisingly, Sophie reminds him of – is hollow because it isn’t contextualized or lacks pay-off. The script possesses emotional moments but, maybe for fear of being too grim, the late screenwriter Melissa Mathison doesn’t feel showing us is necessary.

There may be a lack of emotional power, but there’s no skimping on the humor for children and The BFG aims right for the youngest children. We get the gross-out gags typical of past Dahl works with Sophie hiding in disgusting food – complete with an invented language that will remind older fans of the first time they heard the word “snozzberry” – as well as a fart gag on par with the barf-o-rama moment in Stand By Me.

As Sophie, Ruby Barnhill is a revelation elevating a stock character and presenting personality in lieu of narrative. She’s curious and determined and refuse to have people talk down to her, “don’t little missy me!” She comes up with numerous schemes on her own, although her tendency to leave things out for the bloodthirsty giants to discover does a disservice to her character’s intelligence.

Newly minted Oscar-winner Mark Rylance is wonderful as the big-eared BFG. Though not the hulking behemoth that the other giants are, he’s an outcast like Sophie and the film is strongest when the two bond with each other. Though hesitant to get close to the little girl, Rylance’s giant has a sensitive, magical core expertly captured in his motion capture performance. The other giants, in comparison, lack the humanity as well as the life-like renderings of the BFG; their CGI expressions come off as plasticine, akin to something out of The Polar Express, compared to the otherwise photo-realistic world of Giant Country.

The third act introduces Penelope Wilton, Rebecca Hall and Rafe Spall into the film that, up until this point, has been Sophie and the BFG against the insulated world of Giant Country. Though these human characters spark the late arrival of the plot, it’s handled in a sloppy way. The audience is told children have been disappearing this entire time, but there’s no previous mention – not even a newspaper article – so Sophie’s discovery of it and the resultant knowledge that it’s apparently been happening for awhile introduces a wonky sense of time that throws everything off-kilter.

Though beautiful to look at and well-acted, The BFG never rises above mediocre. It’s doubtful this will be a future classic and it’s far from Spielberg’s best film for children.