One of the great things about middle age is that you forget stuff.

This is problematic when it relates to the location of your car keys, the combination to your gym locker or the date of your future ex-wife’s birthday. But it’s fantastic when it comes to watching movies.

Now that I’m over 39, I find that I have completely forgotten the plot to movies I haven’t seen in a few years. At first this depressed me; it was a sad reminder that yet another mile marker had been passed on the road toward my mortality. But I have come to appreciate this “selective memory loss” as one of the unplanned perks of my impending dotage.

Because, if I spend enough time away from a movie I love, it becomes like new again.

This happened to me with the Dollars Trilogy, Italian director Sergio Leone’s series of ultraviolent, internationally co-produced Westerns from the 1960s. I loved these films when I was younger and watched them often in scratchy, faded, poorly cropped, frenetically panned-and-scanned TV broadcasts. Then I didn’t see the movies for a decade or so, and they receded into a shapeless, cinematic blur in the burgeoning recesses of my over-crowded memory.

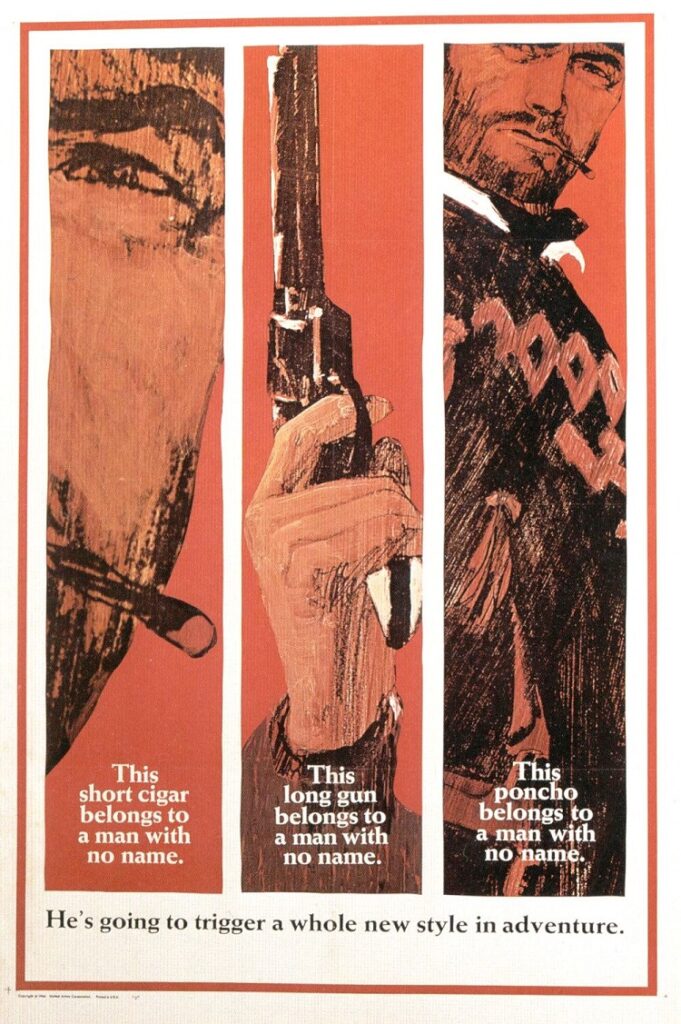

All I remembered was Eastwood’s poncho, the blaring trumpets and Lee Van Cleef riding off into the sunset with that snaggletoothed grin.

Fast forward to this week, when I watched the recently released standalone editions of A Fistful of Dollars and For a Few Dollars More on Blu-ray. I was like a Leone virgin all over again – touched (by the Man with No Name) for the very first time!

First impressions: the films look and sound better than ever – better, in fact, than I thought the source material would allow. Objectively speaking, the image quality on Fistful looks a bit muddy, particularly in the day-for-night scenes. But I chalk that up to the budgetary limitations of a movie made for $200,000 nearly half a century ago, in a format known as “the poor man’s CinemaScope” (aka TechniScope).

Thankfully, MGM did not erase the beautiful Grindhouse Era grain of the source material with digital noise reduction, or any other modern trickery. The film retains the rough-hewn, indie charm that was a key component of its success during its initial theatrical release in the United States in 1967.

For A Few Dollars More, shot a year after Fistful for three times the budget, looks sharp and stunning. The colors are vibrant, and Leone’s signature extreme close-ups – more evident in this sequel than in its predecessor – look like works of pop art.

Both A Fistful of Dollars and For A Few Dollars More are in their original theatrical aspect ratio of 2.35:1 in full 1080p high definition. Each title is available separately, in aggressively priced, bare bones packages that forego the commemorative booklets I never get around to reading.

And they both sound great, which is an important consideration for anyone who appreciates the groundbreaking work of composer Ennio Morricone. The films are presented in English in 5.1 DTS-HD Master Audio surround sound mixes, as well as in mono for the old school purists.

Most of the special features are interviews ported over from previous releases, a few of which appear to have been shot in 4:3 and blown up/cropped to accommodate 16:9 monitors. This is ironic, considering that both films suffered the reverse of this indignity for so many years on television.

Of the special features, the best by far is the commentary track by Sir Christopher Frayling, author of Something To Do With Death, a popular Leone biography. Frayling is a delightful cross between British headmaster and geeked-out fanboy, and his commentaries are must-watch/listen, even for commentary-haters (like me).

A Fistful of Dollars was the first of the so-called Spaghetti Westerns, though not the first Western produced for the Italian market. According to Frayling, 25 Italian, Spanish and West German co-productions were filmed in the Andalusia region of southern Spain between 1962 and 1964 – as the number of Hollywood Westerns was dwindling precipitously.

Between 1950 and 1964, Hollywood’s Western output fell from approximately one of every three films released, to less than one in ten. As the genre devolved into formulaic horse opera and migrated to episodic television, Leone saw an opportunity for reinvention, particularly for foreign markets where demand was higher than ever.

And thus, The Man with No Name was born.

Filmed in the Spring of 1964, Fistful was an unlicensed (and, it turned out, legally actionable) remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961) with 34-year-old Eastwood playing the Old West equivalent of Toshiro Mifune. As an unnamed drifter (someone calls him Joe, but that’s clearly a nickname), Eastwood is the opposite of Mifune’s slapstick Samurai and, while he hews closely to the laconic leading man archetype that viewers had come to expect, the Stranger is a true counterculture anti-hero in every sense.

At the beginning of Fistful, the poncho-wearing Stranger rides in to the Mexican border town of San Miguel, where he insinuates himself into a turf war between two warring clans: the Baxters (representing the corrupt establishment) and the Rojos (the lawless, mafia-like gangsters). It was a storytelling masterstroke on Leone’s part to pit the Anglo family against the Hispanic, particularly for an American audience in the throes of headline-generating racial strife.

The Stranger plays both families against the other, and in the process reunites a beautiful woman with her husband and child. But don’t let that good deed fool you. Over the course of 100 minutes, Eastwood’s character breaks just about every rule in the Motion Picture Production Code, and ends up killing most of the cast.

In fact, the character’s questionable morality led ABC to shoot a five-minute prologue for the TV premiere in 1977, wherein Harry Dean Stanton attempts to provide motivation for the Stranger’s morally ambiguous behavior. Unfortunately(?), Eastwood was not available for (or interested in) this revisionism, so the sequence was shot entirely with a stand-in who was a foot shorter than the man for whom he was doubling. The prologue is included on the Blu-ray, along with an interview with notoriously odd director Monte Hellman (Cockfighter, Two Lane Blacktop), who seems vaguely embarrassed by the whole affair.

Where Fistful was more of a straight-up (albeit paradigm-altering) Western, For a Few Dollars More is somewhere between an homage and a send-up. It’s broader, funnier, and more stylish than anything in its predecessor. Eastwood returns as the Stranger, this time referred to as Manco, due to a leather gauntlet he uses on his gun hand. Now he’s a bounty hunter, faced with competition from the Man in Black, a.k.a. Colonel Douglas Mortimer (Lee Van Cleef), an older, more methodical hired gun with a vendetta.

Both men seek the same quarry, a cackling, drug-addled murderer called El Indio (played with gusto by Gian Maria Volonte, who portrayed Ramon Rojo in Fistful under the Anglicized pseudonym Jonny Wells).

The two bounty hunters initially sniff each other like territorial tomcats, then tangle in a memorable shootout wherein Eastwood’s hat receives the brunt of the damage. Finally, they reluctantly join forces, transforming the film into something of a buddy picture/action comedy, as they unite to bring down the increasingly psychopathic (and scenery-chewing) Indio.

Whether it’s the 300% increase in the budget, or the creative capital afforded by an international smash hit, Leone’s work in For A Few Dollars More seems more confident and assured than in Fistful. He doesn’t just poke fun at genre tropes; he both lampoons and redefines them.

Having earned the time and the funds to achieve his uncompromised creative vision, Leone delivers a film that today feels positively seminal. For a Few Dollars More is nearly perfect, positioned between the spare work that preceded it and the increasingly outsized Leone extravaganzas that were to follow.

For me, reacquainting myself with A Fistful of Dollars and For A Few Dollars More on Blu-ray has been a treat – sort of like visiting with old friends who are aging with remarkable grace. If only I could say the same for myself…

Wait. What were we talking about?