The first director a Western audience thinks of for classic samurai films is Akira Kurosawa. After all, his Seven Samurai is routinely (and with good reason) listed amongst the greatest films ever made. About a third of his entire output of films were samurai period pieces. He is one of two directors who gets an entire chapter to himself in Alain Silver’s The Samurai Film, an important book on the subject. The other director is Hideo Gosha, who directed this pair of films, Samurai Wolf 1 & 2.

Gosha’s samurai came from a more cynical worldview than Kurosawa’s, and no one could call Kurosawa a Pollyanna. While samurai were nominally from a higher warrior class, in Gosha’s world they rarely seemed to have any connection to any code of honor or chivalry. They’re just the guys with the swords. And in this duology, that main guy with the swords describes himself as a vicious wolf.

We first meet our titular wolf, Kiba, munching on rice. Bowl after bowl, the grains sticking to his face. He’s out-scruffying the scruffy sword for hire in Kurosawa’s Yojimbo. But when the innkeeper finds out he has no money to pay for his rice, he offers to work it out in trade, and turns out to be a decent handyman. There’s no mystique to this wandering swordsman, and little romance. What he does have is some honor (and, as the film plays out, he seems to be the only one who does.) Wandering from the inn, he finds some men he’d passed earlier in the day dead on the road. He takes the time to cart the corpses back to town. They’re postmen, and the Wolf finds there’s a conflict between the town’s post office and another government official, Nizaemon.

He wants the post office for himself, and is trying to steal it from its proprietor, a blind widow, Chise. She immediately finds the Wolf intriguing and implores him to stay and help in her struggle. He initially refuses, but when the postmen foolishly try to fight with Nizaemon and his hired swords, the Wolf intervenes. And when the post gets a contract for the delivery of 30,000 gold coins from the shogun, he’s hired outright to protect it. But after the Wolf kills Nizaemon’s ronin, he has another hire up his sleeve – a ruthless samurai murderer.

How Western does this sound? Because every bit of Samurai Wolf feels like a Spaghetti Western, maybe with udon instead of spaghetti. And like a Spaghetti Western, Samurai Wolf has subplots and intrigues where everybody in town has some sort of interest in the approaching gold. And, of course, everything turns out terribly, so by the end of the movie the population of the town is one, maybe two people.

Samurai Wolf 2 has no continuity with the first film except for Kiba, and even less connection to a civilized world. Kiba rescues woman from a group of men harassing her. She turns out to be feeble-minded, and when Kiba fights her harassers off, they swear revenge. But after that misadventure, he comes across a prison convoy, and one of the prisoners is the spitting image of his long-dead father.

There’s no chance it’s him – Kiba saw his father die, and the prisoner is much too young. But he’s too entranced by this father figure to leave the convoy on its own. He follows them, and it’s a good thing since the convoy is attacked by men looking to kill this father figure, Magobei. He was working for a clan that found a hidden gold mine, and they decided fewer people needed to know about it. They framed him for a murder but couldn’t wait for the officials to do the job, lest he talk.

At the same time, the master of the swordsmen Kiba fought off to save the girl wants to challenge him to a one-on-one duel to prove his swordsmanship is better. Oh, and the girl happens to be the daughter of the man who wants Magobei dead.

It seems like a needless series of coincidences, but it actually helps to control and simplify the plot and purify the film’s action. Everything is focused between these three factions: the gold stealers, the swordsmen, and Magobei. Kiba weaves through the middle. But Kiba doesn’t scheme, and he doesn’t plan. All he’s interested in doing is getting to know Magobei, and that thrusts him into the middle of the conflict.

Both films are heavy on action and propulsive forward motion. Wolf 1 has more set pieces and some more self-consciously “arty” sequences. A nighttime duel between Kiba and the ruthless samurai is punctuated with Chise playing her harp. Wolf 2 is more straightforward, but both are brisk movies, neither’s running time exceeding 75 minutes.

When they were released, Gosha’s gritty, somewhat dirty vision of samurai cinema was not that well received. His costumes were simple. His settings were rustic and dusty. There’s very little nobility on display, and little hope. The resemblance to Spaghetti Westerns extends to the setting, especially in the second film, which takes place mostly on scrubby hills and sandy dunes. No towns, no forests, no grandeur. And the violence is suitably bloody. The black and white cinematography still contains many an arterial spray and bursts of blood.

Ironically, though Kiba calls himself a vicious wolf, he’s the only character in the films who ultimately is not completely out for himself. He might be a wolf, but he’s not a lone wolf – he seeks a pack. And it might be the central tragedy of the films that he can’t find one. In both movies, a murderous samurai figure tells him that he will become like them after a few years, without mercy. And the films hold out little hope that it will not be true.

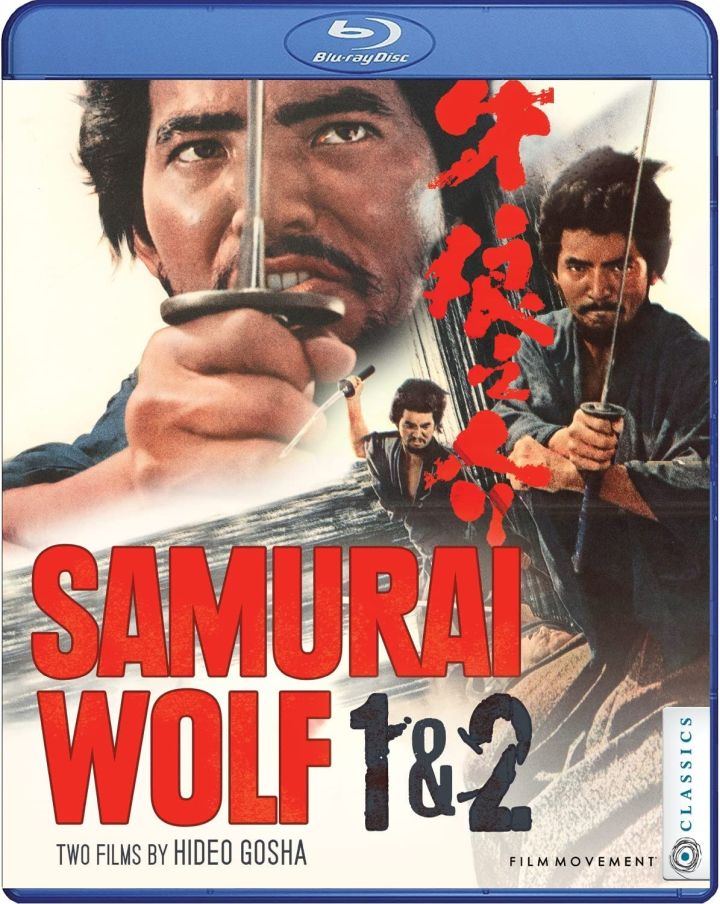

Samurai Wolf 1 & 2 have been released on Blu-ray by Film Movement Classics. Both films are on a single Blu-ray disc. Extras include a commentary on the first film by critic Chris Poggiali. There’s a featurette “Outlaw Director: Hideo Gosha” (16 min) featuring his daughter Tomoe Gosha. Also included is a 20-page booklet with an essay by Robin Gatto.