In this day and age, wherein masses of mindless individuals with no ability to properly implement the usage of the words “literally” or “ironically” in sentences, and who instead oversaturate conversations with superfluous adverbs where there don’t need to be any (and, sadly, you don’t know who you are), there’s another saying that has only grown to become irritably irksome to hear: that of the many references to the “zombie apocalypse.” Why, in less than ten years, the saying has miraculously become older than the walking dead in motion pictures themselves. But it wasn’t always about dead folk rising from the grave in order to consume the fresh flesh of the living, bullets being administered to the heads in order to defeat otherwise unstoppable foes, and pounding progressive rock scores by Goblin.

In fact, once upon a time, boys and girls, cinematic zombies were of a much closer vein to their Haitian folklore origins. 1932’s White Zombie ‒ a title attributed to being the first feature length zombie movie ever made ‒ features walking dead that are completely unlike what we see in contemporary horror movies today. They were usually mere men and women, bound by an unholy trance and forced to do the bidding of nefarious plantation workers. As the ’40s and World War II rolled around, the beasties of this horror movie subgenre began to pop up more, commonly being used as red herrings and sometimes even just for comical effect. One of the few notable exceptions was Jacques Tourneur’s I Walked with a Zombie, the second of several gothic horror classics produced by Val Lewton for RKO Radio Pictures.

The 1950s brought about yet a new era for the reanimated dead: science fiction. Soon, mad doctors and aliens from afar were bringing recently deceased folk back to life for slightly more devious purposes. But it wasn’t until the late ’60s, when shifting winds within the political and civil systems of contemporary America allowed an unknown filmmaker from Pennsylvania named George A. Romero to turn these simple man-made monsters into something more horrific via a morbid twist in his 1968 social commentary, Night of the Living Dead. It was then, for the first time, that zombies were depicted as flesh-eating cannibalistic creatures whose very bite could infect the entire human race. And it was from there that there was no looking back how filmgoers saw the living dead.

Well, almost. After George Romero unintentionally changed the face of this particular subgenre terror for all time (the success of Dawn of the Dead and its many imitators only enabled the newly-established formula to bury the past incarnation), few filmmakers were willing to take the “old school” approach to zombie movies. But, nearly 20 years after walking corpses received a facelift (or is it a “face-rip”?), horror filmmaker Wes Craven ‒ who had hosted A Nightmare on Elm Street only a few years before ‒ decided to show them young whippersnappers how to do it right with an adaptation of ethnobotanist Wade Davis’ 1985 nonfiction account of his journey to Haiti, and certain discoveries he made there concerning once legendary voodoo zombification rites. Truly, what could be scarier than a real-life horror such as being turned into a mindless slave?

Well, one such scarier thing is having your dream job transformed into just another Nightmare from mindless studio executives. For you see, kids, The Serpent and the Rainbow was Wes Craven’s first attempt at making something that didn’t belong to the oft-controversial class of moving picture his career had become so stereotypically associated with ‒ an endeavor he would have to wait an additional eleven years for in order to fulfill (said project, 1999’s educational/music drama Music from the Heart, was the only one of Craven’s efforts to receive an Oscar nomination). And so, while the film version of The Serpent and the Rainbow was most likely beget as something akin to I Walked with a Zombie, the end result would have been better off being titled “A Nightmare in Haiti.”

Here, a greenhorn Bill Pullman takes one of his first big lead roles as a Harvard Man who is sent to Haiti by a pharmaceutical company (in a blissful, pre-Martin Shkreli world) to see if he can’t dig up a drug Haitian voodoo practitioners use to turn people into zombies. (It sounds less far-fetched on film.) But in order to do so, Bill is going to have to dig up a lot more first ‒ starting with an actual “survivor” of zombification (patterned after real life zombie Clairvius Narcisse). A shaky government regime of the time does not help the easy-going white man’s plan of retrieving what is considered to be a rare holy practice of the land, as we soon find out once bad guy extraordinaire Zakes Mokae ‒ who, in addition to his charming demeanor and good looks (to say nothing of his skills with a hammer and nail), is also an evil voodoo sorcerer (or, bokor, if you want to get really technical).

And while most of The Serpent and the Rainbow is set within a fairly conceivable universe, it is as the story unfolds and villain Mokae really comes into play that the whole vehicle begins to divert into troubled, muddy waters. This is especially relevant during the last portion of the film, wherein nightmarish hallucinations straight out of Freddy Kruegerland begin to exhibit themselves in a crumbling reality. It’s a pity, too, because there’s an excellent chance The Serpent and the Rainbow very well could have been the next I Walked with a Zombie: a return to horror that we still don’t have the pleasure of seeing, especially as people who are literally waiting for that ironic apocalypse of the walking dead to happen seem to be perfectly content with direct-to-video torture porn and increasingly brainless works from Zombies named Rob.

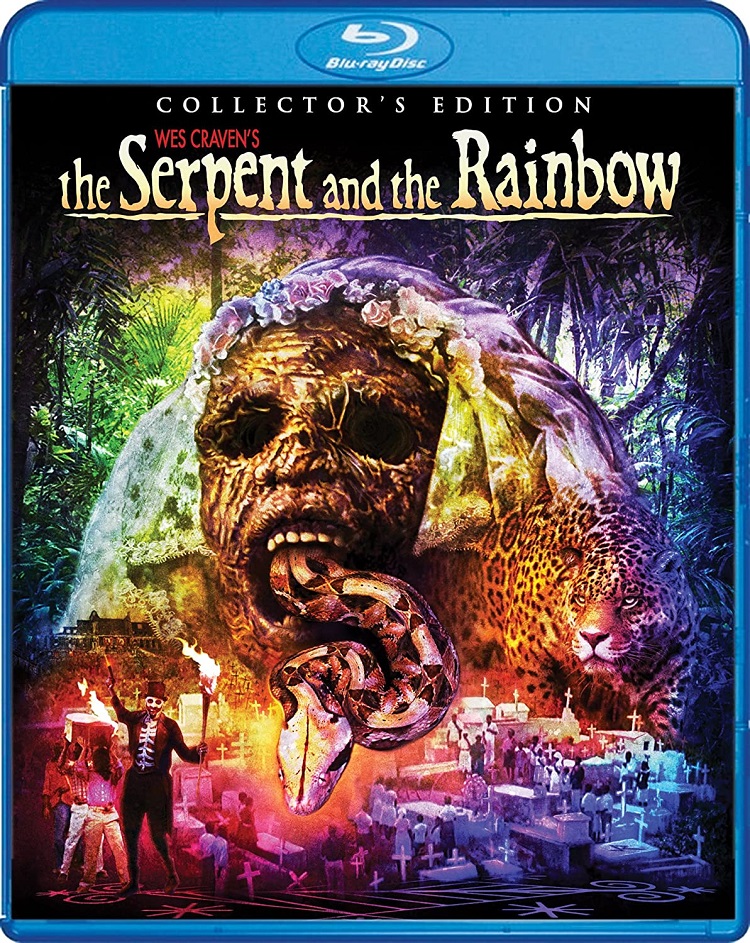

Despite the fact the suits at Universal Pictures insisted Craven transformed The Serpent and the Rainbow into a horror film (despite the fact horror movies were practically dead on their feet at the time), it remains something of a classic with most fans of the genre. And while the film ‒ which also stars Cathy Tyson, Paul Winfield, Michael Gough, and Paul Guilfoyle ‒ is as rough around the edges as the setting of the film itself (especially when I look at it again, nearly thirty years down the line), it is nevertheless fun to see these living dead walk once again via a new Blu-ray release from Scream Factory. The feature film it presented in a 1.85:1 transfer, which, despite a few flaws of its own (most likely inherent in the original materials themselves), looks pretty stellar throughout.

In addition to its new HD video transfer (it looks loads better than the previous SD-DVD issues), The Serpent and the Rainbow sports a great DTS-HD MA 2.0 soundtrack which nicely highlights Brad Fiedel’s score (which often comes close to sounding like another film Paul Winfield co-starred in, The Terminator). English subtitles are in tow here, as are several bonus features. The first is an audio commentary with Icons of Fright’s own Rob Galluzzo, who is joined by star Bill Pullman. Mr. Bill’s recollections are joyful to hear, though I regret to inform you the commentary is not feature-length: due to schedule conflicts, the actor has to bail from the recording booth nearly an hour into our feature film so he can fly out to New Mexico to shoot scenes for Independence Day: Resurgence (that’s show business for you, kiddies!).

Pullman’s comments on The Serpent and the Rainbow are (sometimes noticeably) re-edited and laid over a making-of short that features additional insight from Director of Photography John Lindley, the father and son special effects wizard team of Lance and David Anderson (the latter of whom is married to A Nightmare on Elm Street star Heather Langenkamp), and ‒ via webcam video ‒ Wade Davis himself. Another captive from the Internet, this time in the form of a low-resolution TV spot culled from someone’s home video recording, is also present. Fortunately, the original theatrical trailer included here (which is presented in open matte) hails from a much better quality source. Either way, it’s nice to have a contemporary home media presentation of this underrated (if uneven) film with extras.

In short: Traditional zombies aren’t quite dead, so don’t go burying this one just yet.