Written by Anastasia Klimchynskaya

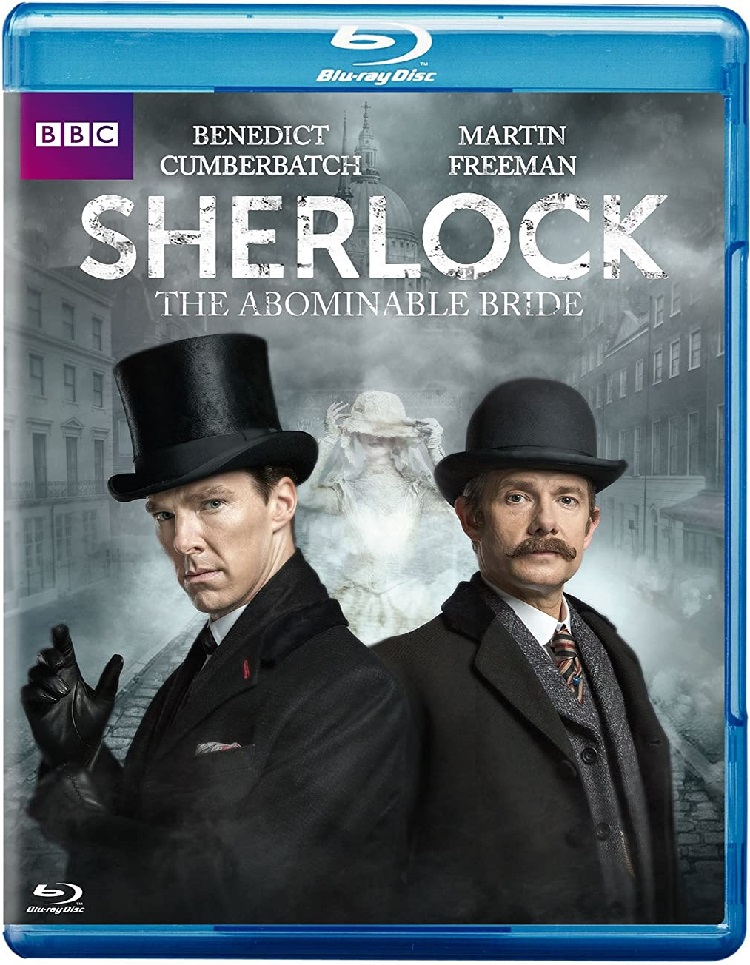

It’s becoming almost a biannual for the New Year to open with a new episode of the BBC’s Sherlock. The absolutely excellent, but excruciatingly infrequent, show usually airs once about every two years, and has now made a habit of helping Sherlockians and geeks the world over ring in the New York with complex puzzles, convoluted plots, and clever dialogue. This year was a special treat: eschewing (seemingly) their modernization of Sherlock Holmes, Sherlock went back to the Victorian period for a Christmas (New Year’s?) special. It’s an episode the hype, hysteria, and emotions around which are possibly trumped only by “The Reichenbach Fall,” because threatening to kill off your main character, as Steven Moffat did two years ago, kind of does that.

In the past couple of weeks, those reactions have quieted down some, as some viewers avidly rewatch the new episode and others simply come to terms with its existence. But it remains, I think, one of the most controversial in the Sherlock canon, precisely because it’s set in the original era of the stories (ironically).

And yet, to say that “The Abominable Bride” is merely a Victorian rendition of Sherlock Holmes would be to do it a gross injustice. The episode is about three plots in one, all of which have drawn the ire of viewers, and yet all of which are, arguably, what make it stand out.

Starting heartily in the Victorian era, with Holmes and Watson’s first meeting, the episode at first appears to be an accurate period piece. But slowly, slowly, we realize that something’s not quite right. Anachronisms slip in. Sherlock refers to his brain as a “hard drive,” talks about the “virus in the data,” and at first it flies by us, because we’re so used to that expression from a modern Sherlock, and then we realize there were no hard drives in the 1890s. It’s details like this that Sherlock has always excelled at – the ones right in front of our eyes, but the ones we take for granted, that make every viewing of the show a puzzle. And slowly, as we register the anachronism, the revelation comes that the entire story has been happening in Sherlock’s head, or, more accurately, his Mind Palace.

That’s the second of the three complex threads that come together into the plot of this episode. If I were keen on using the over-used clichés of detective stories (most of them invented by Conan Doyle), I’d call it a “tangled skein” with a “scarlet thread of murder” running through it, but I’ll leave that to Watson’s prose in The Strand. The entire world conjured up by this episode, as it turns out, is a look into Sherlock’s psyche, and it’s another thing that makes this episode stand out- how many shows allow its viewers an eighty-minute look into the protagonist’s brain while still keeping the mystery alive? Sherlock’s mind, as we learn, is convoluted, non-sensical, non-linear, and rather like a Doctor Who episode, full of “timey-wimey,” but that’s exactly a point. A brain like Sherlock’s would not produce a narrative that is in any way linear or in accordance with the conventions of storytelling, and it’s all the better for it.

This non-linear plot also furnishes the third thread of the episode: the actual mystery. At first, it appears to be a simple case of a woman coming back to life to murder her husband (and in Sherlock Holmes’ world, that is, indeed, the definition of simple). But it soon turns out that the case of a character coming back to life after blowing their brains out is a metaphor for another, much closer and much more pressing case – that of Moriarty, who, at the end of season three, appeared to have returned despite having killed himself in “The Reichenbach Fall.” It’s been a point of contention since “His Last Vow” aired two years ago, and this episode seems to have resolved that problem, which Sherlock solving the case of Emilia Ricoletti, who used a double to come back to life – and consequently claiming that “Moriarty’s dead. But he’s back.”

In short, “The Abominable Bride” is an episode that took about a hundred steps without taking a single one, and I mean that as a compliment. It threw a dozen puzzles at the viewer, but refused to solve any of them. That’s not a bad thing. With this insight into Sherlock Holmes’ mind, with its mysteries, we’re also invited to use his method. We’re given puzzles – about the character and personality of Holmes, about the ghosts from his past, about the return of Moriarty – but none of them are resolved, even as we’re given the clues to solve them all. And so this episode at once advances the story and does not – for, plot-wise, about five minutes have passed in reality. And yet in our minds, hours have passed and the plot has been advanced and the characters have been developed. And that’s all we could ask for from a story, really.

And to those that complain about the cop-out of the explanation that it was all in Sherlock’s head, I will end with several wise words from Albus Dumbledore:

“Of course it’s all in your head, but why on earth should that mean that it wasn’t real?”