The strange allure of musty, humid air and untold perils that only an untamed marshland can offer has fascinated many a mere mortal ever since man first ventured into such beautiful, disease-ridden quagmires. But the equal abundance of a wide variety of life (whether it be that of an animal, plant, or parasite) is rarely examined as much as a swamp’s keen ability to suck the life out of any creature with nary a lick of sense in its noggin. And so, most of the movies set in a bayou usually tend to be of either hicksploitation or monster origins. Recently, the Warner Archive Collection unveiled two entirely different swamp features from the ’50s ‒ neither of which had seen a release on home video before the WAC wandered deep into the boggy depths of cinema to recover them.

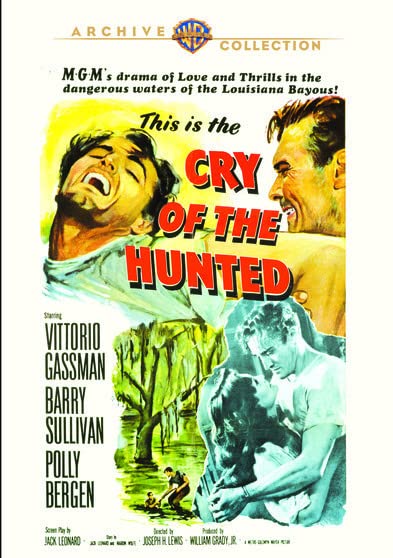

Much like the swamp’s variety of life and death itself, features set in such a setting can be of varying degrees of good and bad. And our earliest entry, 1953’s Cry of the Hunted tends to lean a great deal into the latter category, in my humble opinion. Beginning in the contemporary asphalt slough of Los Angeles, the tale spends a generous amount of time establishing a setup that grabs the viewed by the throat much in the same way a weiner dog napping on the inside of a house instills terror within the hearts of hyperactive squirrels playfully mucking about up in the trees on the outside. And that’s being generous: in actuality, Cry of the Hunted is a dull, dreary film ‒ its only saving grace being a brief scene with hefty co-star William Conrad attempting to chase a wily Vittorio Gassman up Angel’s Flight Railway.

Gassman is the film’s top-billed (but sparingly-used) lead here, cast as a hapless, love-obsessed schmuck whose minor part in a robbery has him serving a lengthy incarceration in solitude. When the L.A. prison’s golf-obsessed warden (Robert Burton, one year after Sky Full of Moon and one decade away from his final murky masterpiece, The Slime People) demands Lt. Barry Sullivan get the names of Gassman’s former accomplices just to get the story rolling. So, our lawful hero becomes obsessed with Gassman (because it’s a gas, man!) while tough William Conrad obsesses about grabbing Sullivan’s job, as Sullivan’s on-screen wife Polly Bergen obsesses about meatloaf. (Get ready for lots of sexist ’50s comments combined with manly men slapping each other about before collapsing to enjoy a smoke together!)

Eventually, Gassman escapes William Conrad’s groundbreaking stride, and miraculously makes it back to Louisiana on a train. Which the authorities know about, but they still send Barry Sullivan way out of his jurisdiction to apprehend him in Louisiana just the same. Because how else would they have a story otherwise, right? A bizarre swamp fever hallucination scene befalling Sullivan (spelled with two Ls; a reference to one of the film’s many cutesy running gags) prominately stands out here, while the climax ‒ wherein Barry ignites a presumably catastrophic swamp fire to flag down help so everyone can go home happy benefits from future First Alert spokesman William Conrad being the first to arrive at the scene and save the day (somewhere, MST3K‘s Dr. Clayton Forrester and TV’s Frank are giggling about this, I’m sure of it).

If it seems rushed, it can only be because MGM’s B unit “bayou noir” Cry of the Hunted‘s director, Joseph H. Lewis, started out as the (usually uncredited) editor of Republic Pictures oaters, serials, and Poverty Row quickies (he was editor for the ’56 Lon Chaney schlocker Indestructible Man, which featured another foot chase up Angel’s Flight). Story/screenwriter Jack Leonard also penned a number of other noirs, notably The Narrow Margin (which saw a 1990 remake starring Gene Hackman), and another ‒ more popular ‒ 1953 crime drama offering, Man in the Dark. Assistant director Joel Freeman worked on such bonafide classics as Adam’s Rib, Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, and Blackboard Jungle before later producing the blaxploitation classic Shaft.

The Warner Archive Collection presents this lonely ol’ swamp pic in its original 1.37:1 glory and boasting a lovely transfer. No accompanying trailer is included in this instance, but it’s probably just as well, as there really isn’t anything going on here to promote. Thankfully, I can say the exact opposite of yet another neglected photoplay that takes place in a distant wetland, 1958’s Wind Across the Everglades. Shifting locales once more to the legendary Florida national park, the tale ‒ set in the early part of the 20th century, long before the state became the civilized, well-behaved sanctuary of gun nuts, meth addicts, and Jeb Bush it is today ‒ brings us a fictionalized take on the life of game warden Guy Bradley, who was killed in 1905 by plume hunters determined to upset the delicate balance of nature. Because Florida was already Florida even then.

Here, the great Christopher Plummer delivers an impressive second role in the moving pictures as Walt Murdock, a young ornithologist whose fiery devotion to winged creatures and strong will to fight greedy ignorant bastards lands him a job as game warden almost immediately after arriving in Florida. This does not impress most of the local yokels, naturally, and it isn’t long before “Bird Boy” is both the hunter and the hunted: wandering the dangerous fenlands in search of poachers, while becoming the main interest of the area’s most notorious swamp rat, the villainous Cottonmouth. And who is that red-bearded heavy with the deadly pet snake in his pocket, reigning supreme over his own kingdom of outlaws and psychopaths deep in the swamp? Why, it’s folk singer Burl Ives, kids ‒ delivering one of the cruelest performances of his career in a role that will seriously have you reconsidering playing his albums at this year’s ugly sweater Christmas party!

But of course, Burl’s magnificent accomplishment as one of cinema’s most cunning bayou rats is one of Wind Across the Everglades‘ most captivating highlights: cool, calm, and collected, but ready to strike at any second. Likewise, Christopher Plummer’s endeavor as the hero is a multifaceted characterization that deserves heavy examining. Plummer’s Walt Murdock is decidedly awkward in public when he isn’t serving the course of justice, but just as powerful of a mind to reckon with as his adversary ‒ especially once he ventures directly into the heart of the snake pit for the conclusion of the film. A young Peter Falk makes his film debut as one of Ives’ minions (most of whom are also quite multifaceted for such minor roles), and is joined by a wonderfully versatile assembling including heavyweight Tony Galento, circus clown Emmett Kelly, and gravelly-voiced Pat Henning.

The great, odd casting choices continues with legendary stripper Gypsy Rose Lee as the proprietress of a local saloon in this criminally neglected mini-masterpiece that has become a subject of scrutiny with many film scholars due to its maligned production. The one and only Nicholas Ray (Rebel Without a Cause, The Lusty Men) was originally behind the camera calling the shots (and who is still credited as director), giving much of the film its beauty. But Ray’s vision ultimately did not go along with that of writer Budd Schulberg (On the Waterfront, A Face in the Crowd) and his producer brother, Stuart, so Mr. Ray was swamp fired from the film before its completion, with one or the other Schulberg sibling (possibly both) taking over ‒ reportedly discarding a lot of Ray’s footage in favor of his own (as well as taking over the editing of the film).

But despite its issues on the technical side of the camera, Wind Across the Everglades emerges as something to see because of what lies on the visible end. And once you compare it to the boggy bomb that is Cry of the Hunted, you’ll be able to appreciate it all the more. Plus, where else are you going to see Burl Ives, Christopher Plummer, Gypsy Rose Lee, and Peter Falk all at once? Wind Across the Everglades receives an anamorphic widescreen transfer from the Warner Archive Collection, culled from the best sources available. For the most part, the presentation is beautiful, though a good half of a reel was obviously in a state of disrepair (or maybe that was the Schulberg footage, ha-ha!), but it won’t take away from anyone’s enjoyment. The recommended Manufactured-on-Demand release also includes the film’s original theatrical trailer (which is strangely missing all of its title cards) as an extra.