Having already proved himself as the biggest Douglas Sirk fan on the planet, Todd Haynes improves upon the homage/pastiche of Far From Heaven, delivering a full-blooded melodrama in Carol. Far From Heaven is an achingly beautiful film (shot, like Carol, by the great Edward Lachman), but it sits back a bit, the emotions not nearly as expressive as the sublimely saturated color photography.

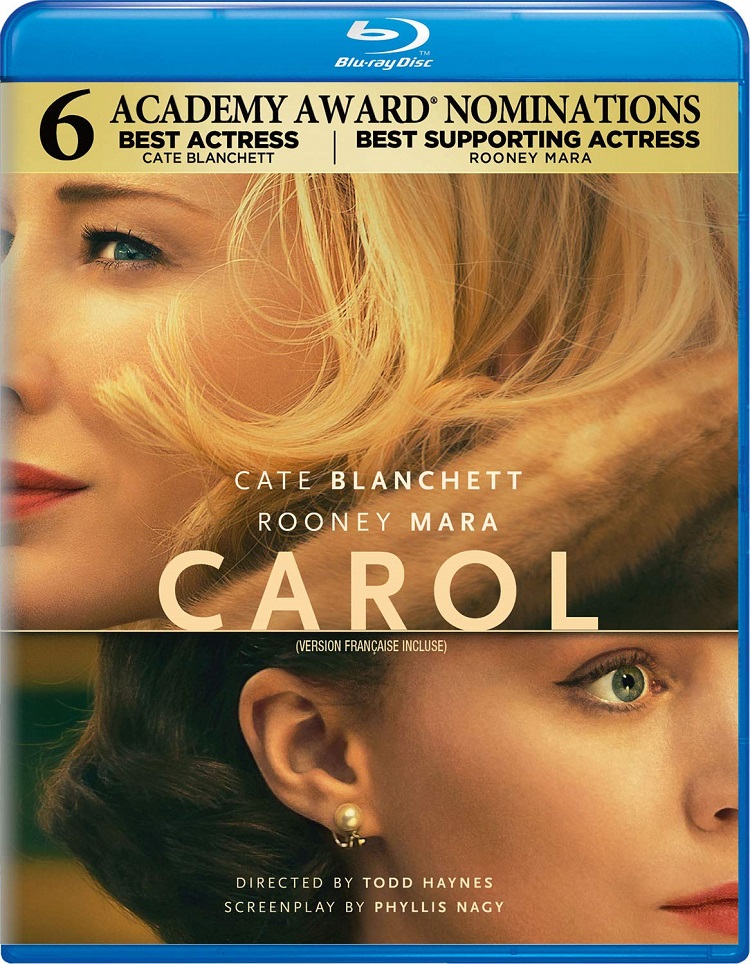

In Carol, as sublimated as the emotions are in a film about lesbian lovers set in 1950s New York, the passion still burns in every frame, thanks both to the yearning, deeply felt performances by Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara, and Haynes’ formal chops. His bifurcated shots can certainly reveal a Sirkian influence — frames within frames are common, like Mara peering into her locker at a pair of gloves or characters watching a film from the projection booth — but the way he makes abstract otherwise ordinary images of windows and door frames and floor grates might be worthy of its own moniker. Haynesian? Whatever you want to call it, the way the film visualizes earth-shattering emotions in the midst of the ordinary is pretty remarkable, and yes, gorgeous.

Based on Patricia Highsmith’s semi-autobiographical novel The Price of Salt, Carol features Mara as Therese Belivet, a clerk in a department store’s toy department with aspirations of becoming a photographer. An encounter with Blanchett’s Carol Aird is charged from their first furtive glances across the store, Therese awed and slightly bashful in a Santa hat; Carol impossibly elegant in fur, and surely not interested in deigning to a meaningful interaction with a customer service worker, right? Blanchett’s performance here allows one to feel every one of the constraints imposed on her — from social to sexual — and her restrained, but firm resolve in overcoming them.

Their friendship develops over a series of ostensible niceties — Therese returns Carol’s forgotten gloves, she thanks her with dinner — with small gestures and mannerisms suggesting their deepening bond. Haynes’ storytelling isn’t exactly elliptical, but Therese and Carol’s relationship feels more like the product of deferred moments than grand pronouncements. Plot mechanics are engineered through Carol’s nearly estranged husband Harge (Kyle Chandler, making a smaller part feel exceptionally complex), who uses her same-sex attractions as ammunition in a custody battle, but Haynes resists social-issue melodrama.

Instead, this brand of melodrama is a highly concentrated, bottled-up, and ultimately, incredibly moving romance. There are enough individually great contributions here to make the film one of the year’s best — Lachman’s 16mm photography, both of the lead performances, Haynes’ elevation of the seemingly insignificant with his images. Taken together, it’s hard not to resort to hyperbole. For now, let’s just call it unmissable.