On Monday, rioting broke out amid a Protestant Orange Order parade in Belfast after it reached a stretch of road inhabited mostly by Catholics, republicans, and nationalists; at least eight people were injured. This, nearly 44 years after the Ballymurphy Massacre, which occurred in Belfast in early August 1971 and today remains a dark spot in the hearts of the Irish. At surface level, it can be easy to pick sides when reviewing history or current resurgences of turmoil. But what director Yann Demange asks in the extremely gripping and often gut-wrenching ’71 is: Can you always trust your loyalties?

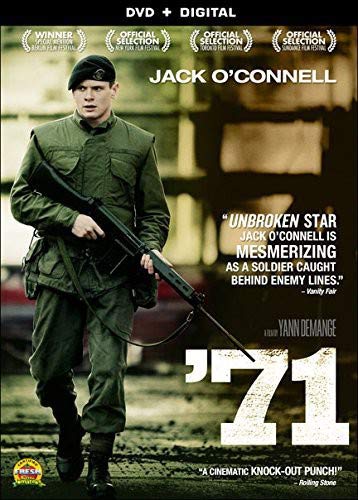

The film observes The Troubles through the eyes of Private Gary Hook, a young British soldier whose regiment learns of its deployment to Northern Ireland instead of Germany at the beginning of the film. Before leaving, Hook (Unbroken star Jack O’Connell) assures his younger brother, who is being brought up in a care home, that he’ll be safe—the troops aren’t even leaving Britain after all.

After settling in their Belfast-based barracks and hitting the war-torn streets for the first time, the soldiers are immediately made aware that because they’re British and affiliated with the military, they’re targets for angry poo-hurling children and brave, confrontational loyalists. They’re also not as prepared as they could’ve been for deflecting rocks aimed at their heads, because their comparatively posh-sounding lieutenant (Sam Reid) ordered the men to go in without riot gear as a gesture of civility.

Everything goes off the rails as the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) searches every house on the predominantly republican Falls Road, beating uncooperative citizens along the way. The angry mob, alerted by the community’s women who furiously bang garbage can lids against the sidewalk, grows, and young and old alike endanger themselves in the name of civil rights.

Caught in a moment somewhere between bemused and horrified, Hook sees that a young boy has run off with a soldier’s rifle. In an attempt to retrieve it, he and another soldier are taken down by a group of young men from the Provisional IRA. The rest of the British regiment flee, leaving their boys behind; Hook manages to escape with his life, but he has to fight for it every hour into the early morning.

What ensues throughout the afternoon and after dark is really the thought-provoking core of this film. We watch Hook, who at one point admits to the young son of a man killed by the IRA that he doesn’t know where he falls in the Catholic-Protestant divide, safeguarded both by people who should be friends and should be foes. But the reality of the situation is that such definitions are ever changing, particularly when human nature comes into play.

One stirring example of this is Sean (Barry Keoghan), a young member of the Provisional IRA, whose life should be focused on school and hanging out, but who instead hides an arsenal of weapons in his room. We watch him, more than once, grapple with what he is supposed to do in the fight against the British versus what his compassionate heart wants him to do.

Another particularly affecting moment is when former army medic Eamon (Richard Dormer), who with the help of his daughter tends to one of Hook’s many wounds, tells the soldier, “It’s all a lie. They don’t care about you. You’re just a piece of meat to them.” He’s talking about the army, but what Demange (who directed a few episodes of the riveting 2009 miniseries Criminal Justice) and screenwriter Gregory Burke suggest with this story is that in the throes of war, footmen (and women) are all disposable, no matter which side you’re on and regardless of whether the organization is government-run or far underground. Loyalties, too, are lost when push comes to shove; and somehow in all of this, the often corrupt bigwigs running the show carry on, while the people who have deeply invested their hearts in a cause die.

The cast, filled with up-and-coming Irish actors, and led by O’Connell, who plays an exasperated, pained soldier to a T, even with very few speaking lines, is excellent. David Holmes’ electronic score drives the ceaseless momentum; and from a cinematic perspective, the use of handheld cameras for much of the action sequences throws the audience right into the narrow roads of Belfast, creating a tense, claustrophobic environment no one would want to be in in real life. And that’s another glaring truth to take away from ’71: It’s indeed a “knock-out punch!” It’s nothing short of thrilling, right up to the ending. But when you remember that events like these took place—many died in the name of loyalty, nationalism, sectarianism, and because some were betrayed by the very people who got them fighting in the first place—it’s far less thrilling.